China’s tech ambitions hinge on 20 electric versions of Detroit

Pieces of an electric car hang from the ceiling of the Chinese real-estate developer’s showroom, evoking an edgy installation at a modern art museum. In reality, they’re a symbol of the nation’s industrial ambitions.

Just down the neatly manicured road, about a dozen skyscrapers rise from the fields as Shunde New Energy Vehicle Town takes shape inside the city of Foshan, part of southern China’s manufacturing heartland. Local officials boast that their planned hub for EV production and research could eventually generate 100 billion yuan ($15 billion) in revenue for the hometown economy.

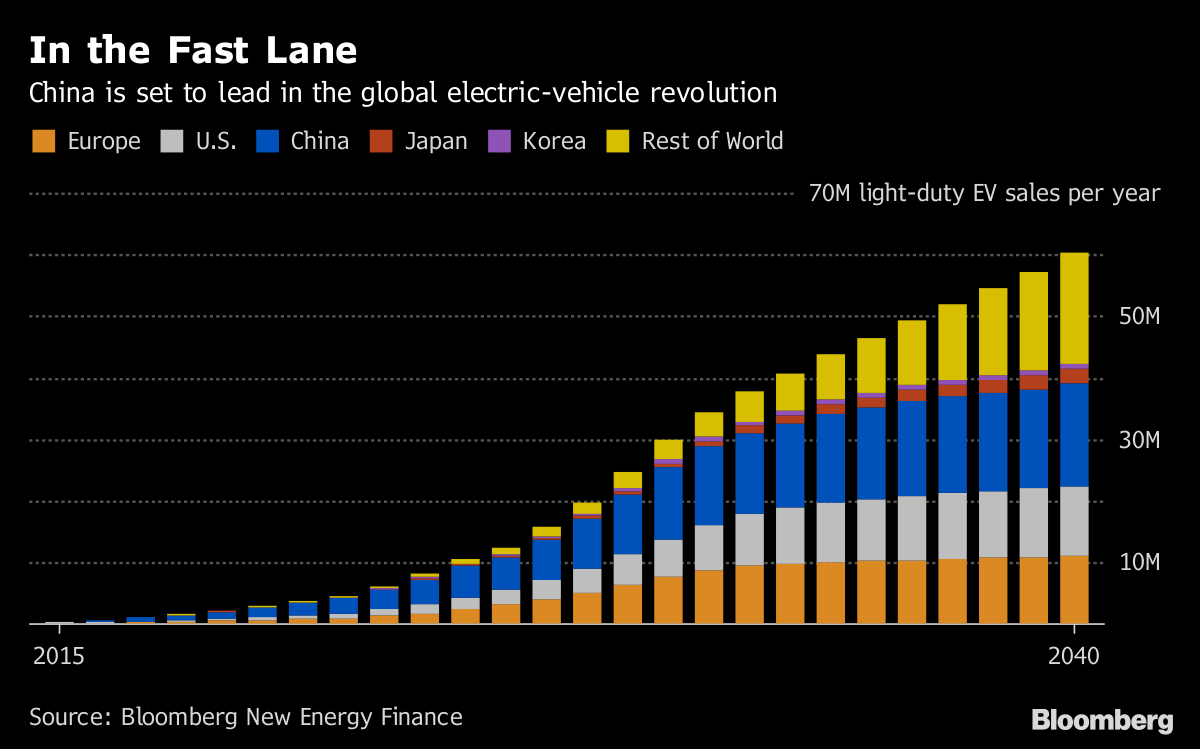

Shunde is one of at least 20 electric-centric versions of Detroit under construction as China goes all-in on a technology projected to sell in record numbers this year. President Xi Jinping wants the nation’s 500 electric car makers to be magnets for ancillary industries as he pushes to build a manufacturing superpower by 2025. That blueprint — meant to make China more self-sufficient and diversify an investment landscape dominated by volatile property and equity markets — has become central to the U.S.-China trade war.

The amount of investment committed to developing these EV towns is a staggering 209 billion yuan — equal to about $30 billion — so far

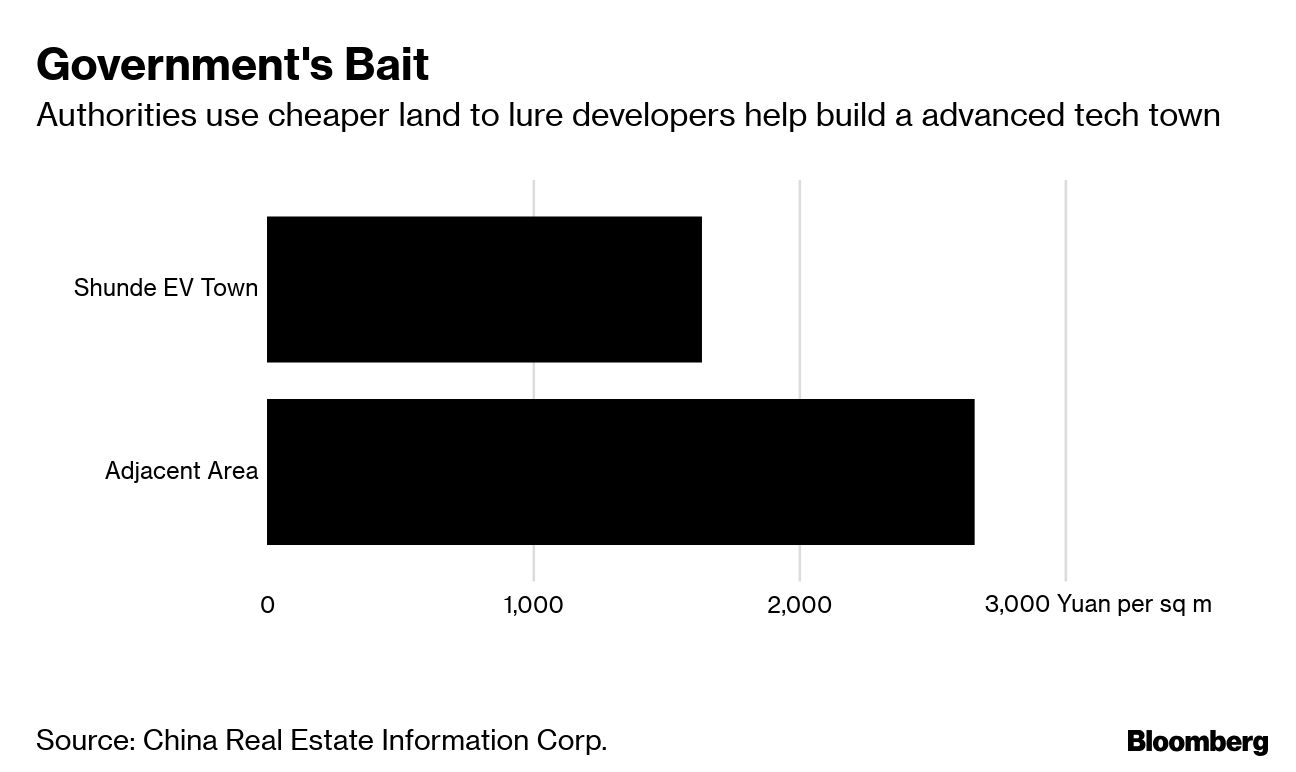

Municipalities needing ways to recalibrate their economies want a piece of that plan. They’re offering cheap land, tax breaks and housing subsidies to carmakers, parts suppliers and engineering labs in hopes of attracting thousands of high-technology jobs in the burgeoning EV sector.

“The new-energy vehicle industry is a bet local governments must take,’’ said He Xiaopeng, chairman of Xpeng Motors Technology Ltd., an EV startup backed by e-commerce giant Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. and Taiwan’s Foxconn Technology Group. “A successful EV maker could bring at least 200 companies in the industry chain into a province.’’

The amount of investment committed to developing these EV towns is a staggering 209 billion yuan — equal to about $30 billion — so far, according to Bloomberg calculations based on public announcements. The commitments range from fixed-asset investments to development costs by carmakers, private capital and local government-backed entities.

The other hubs include Geely Automobile Holdings Ltd.’s plan for a research and production base in Yiwu, LeEco Vehicle Ecological Town in Huzhou and Self-Driving Auto Town in Xiamen.

The towns are typical of China’s command-led approach to its economy. Enthusiasm at the top levels of government for a particular industry trickles down to the hinterlands, which often respond with experiments recalling the movie “Field of Dreams”: build it and they will come. Localities erect industrial parks, apartment buildings and schools, lay out their incentives and then hope businesses will take up their offers.

That’s happening about an hour outside of Beijing, where the government is constructing a Fund Town that’s meant to be a hub for the almost $2 trillion private funds market. More than a dozen towns designated as financial zones are scattered across the country.

Between 2009 and 2017, China spent about $36.5 billion subsidizing EV sales, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. China now accounts for more than half of all passenger EV sales worldwide.

China’s rapid urbanization vacuumed up available land tracts, eventually pushing prices higher and triggering tougher zoning laws. By committing to EVs, local officials may find it easier to get central government approval to redevelop scarce farmland and offer it at below-market rates to lure commercial tenants. That’s attracting some of the nation’s biggest developers, including Country Garden Holdings Co. and China Evergrande Group.

Shunde government officials didn’t return requests for comment. Foshan mayor Zhu Wei said last year the city would offer favorable policies and services to the NEV sector because it’s a strategic emerging industry, the Foshan Daily newspaper reported.

Shunde NEV Town is being constructed by Country Garden, China’s largest developer. To win the plots, the company promises to bring EV-related businesses and to meet tax revenue targets.

“The industry chain is far more comprehensive than car manufacturing,’’ said Liu Wei, who’s overseeing the project for Country Garden. “We’re well aware the fever will fade, but some emerging firms will grow, and that’s who we want to house.”

Prices in what are officially referred to as “characteristic small towns’’ are an average of 49% cheaper than in adjacent plots, according to a China Real Estate Information Corp. study last year.

That helped Country Garden pare office rents by as much as 25% from market rates. And those businesses need skilled workers, so the government offers subsidies of as much as 6 million yuan to help them buy homes.

“The towns have at least one key resource that EV makers and suppliers are eager to own: the land,” said Cui Dongshu, secretary general of the China Passenger Car Association. “That will naturally attract them to move into the towns.”

“The towns have at least one key resource that EV makers and suppliers are eager to own: the land”

Governments around the world are supporting EVs, Zeng said. The U.S. subsidized purchases of EVs and the state of Nevada approved a $1.3 billion incentive package for Tesla Inc. to build its battery gigafactory there.

So far, Country Garden has attracted startup Youxia Motors, autonomous sightseeing carmaker Beijing Zoominbot Automotive Technology Co. and 57 other tenants, including research houses and venture-capital firms. More than half of its available office space is occupied, Liu said.

Youxia, which has raised at least $1.3 billion and is expected to launch its first model this year, didn’t return requests for comment.

The town is planned as a two-square-kilometer area. Sketches show schools, hospitals, a subway line to the airport and a version of New York’s The High Line.

Yet the EV towns are developing just as China’s overall auto sales crater. And while sales of passenger EVs are projected by BloombergNEF to reach 1.6 million units this year, that’s likely not enough to keep 500 companies’ assembly lines humming.

EVs still only account for less than 5% of total car sales in China, and the government is cutting subsidies to force makers to thrive on innovation instead of handouts.

Those factors have some analysts seeing flashing red lights ahead.

“Most of those EV towns will fail,’’ said John Zeng, managing director of LMC Automotive Shanghai. “This wave of electric-vehicle building will come to a life-or-death moment. When EV carmakers are being squeezed, the ‘EV Town’ bubble will burst.’’

A visit in March to Shunde found its voltage a bit low. No one in Country Garden’s showroom could name the suspended car’s make or model. And there were few gearheads around, with most offices seemingly empty, on a weekday.

In January 2018, Country Garden announced its first anchor tenant — EV battery maker Shaanxi J&R Optimum Energy Co. But the company struggled to pay its debts and stopped cooperating with Country Garden, forcing the developer to find a smaller substitute.

Still, Liu is optimistic the sleepy district will one day morph into an electric Detroit.

“I admit that the EV sector is still working its own way,’’ Liu said. “But we have been well aware of sector challenge since planning it two years ago, and we’re confident that we can adapt to the change.”

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments