China’s big commodity inflation scare is easing — for now

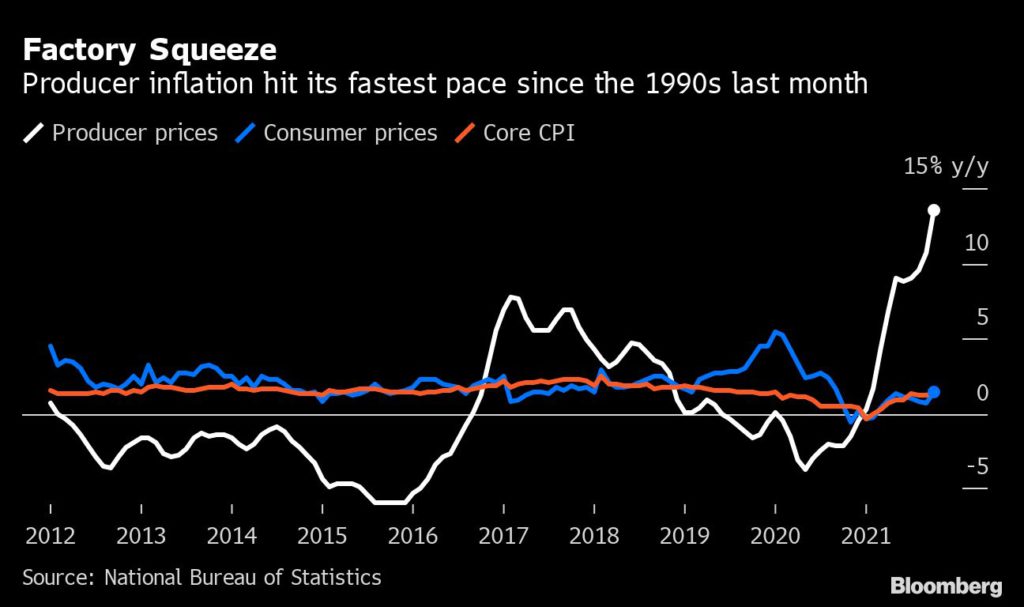

The commodities boom that helped propel producer inflation to a 26-year high in China is showing signs of waning, with the forces that pushed prices up over the past year now in retreat.

An energy crisis that fueled record coal prices looks becalmed for now, while aggressive efforts to stamp out virus outbreaks are wearing down consumer travel and therefore demand for jet fuels. Meanwhile, the liquidity crisis surrounding China’s highly indebted property developers is vanquishing hopes for a rebound in steel and copper.

While commodity-market bulls outside China point to dwindling inventories for oil or metals to argue for higher prices, investors inside the world’s second-biggest economy are cautious, according to Xiao Fu, London-based head of global commodities strategy at an overseas unit of Bank of China.

“There isn’t massive interest to chase prices higher, and there is quite a lot of pressure on buyers,” she said by phone. “For China, the inflationary pressures may be a bit more contained than overseas.”

Still, a lot could change heading into 2022. The Winter Olympics loom, and Beijing’s emissions policy continues to shift. Some investors are also holding out hope for more support from the central government for the reeling property sector that will in turn prop up metals demand.

Also, while most commodity prices are stabilizing, they are doing so at relatively high levels, especially versus a year ago. And the effects of earlier surges are still rippling through the economy. High electricity prices, for example, risk raising costs for manufacturers of everything from cars to clothes.

Winter

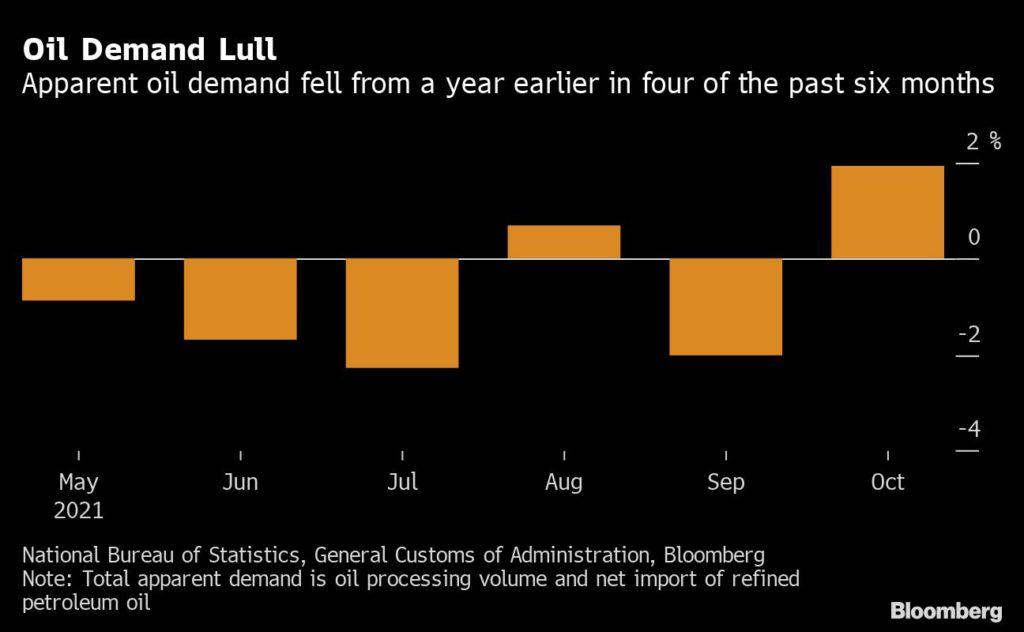

China’s moves to eliminate the coronavirus are getting more extreme, as the country becomes the only place left in the world that won’t accept the pathogen as endemic. With restrictions intensifying in several places including Beijing over the past month, travel has dropped with IHS Markit estimating a 10% fall this quarter for jet fuels.

Gasoline demand is weakening as consumers buy fewer cars or use them less. And in diesel, a Beijing-coordinated campaign to ramp up production and slash exports averted a supply crisis and stabilized inventories.

As temperatures drop, the central government’s monumental mining push since September’s power crunch probably will avert another large-scale energy shortage: coal prices remain at less than half the October peak and stockpiles are closer to healthier levels. That’s eased pressure across all energy markets and along coal’s supply chain.

China will also want clear blue skies for the Winter Olympics that kick off in early February, crimping both oil supply and demand as companies comply with environment dictates, said Yuntao Liu, analyst with London-based consultant Energy Aspects.

Nevertheless, severe winter weather could test energy supplies by raising heating demand. Soaring natural gas prices from Europe to Asia have already prompted a Beijing official to warn of some supply shortfalls during winter. Domestic LNG prices are near record highs, and some Chinese buyers are looking to import again.

Reforms

In China, it’s inevitably regulatory action that has the most decisive impact. That’s been the case in the second half of the year for metals like steel and copper as the real estate sector plunged into a debt crisis with no government bailout in sight.

Iron ore — the raw input for steel — fell by nearly two thirds after peaking in a first-half demand boom. Construction activity has contracted as home-buying fades, forcing steel output to its lowest level since December 2017.

Banks including Citigroup Inc. expect more support for the sector ahead of a crucial Communist Party Congress in late 2022, but there’s few expectations for a sharp reversal in policy, especially because any such move could add to inflation in China.

“The next one to three months will likely see weakening supply and demand across most metals, both seasonally and property-related,” Citigroup analysts including Tracy Liao wrote in a note. Steel and iron ore are immediately vulnerable, they said, while slowing home completions and consumer-appliance purchases will hit copper and aluminum.

The strength of government moves to lower carbon emissions could also re-ignite inflation by capping industrial production. That’s particularly true in aluminum, a prime victim of President Xi Jinping’s initial efforts to target the biggest energy-guzzlers.

On top of that, electricity reforms rolled out in some regions amid the recent power shortages have handed power generators more leeway to raise prices for their industrial consumers. Some regions have hiked prices by as much as 80% for industrial sectors like aluminum smelters, threatening cost pressures.

“These reforms will allow inflationary pressure to flow from coal prices to power prices and then through all the industrial sectors,” said Yanting Zhou, Beijing-based economist at researcher Wood Mackenzie. “There will be pressure for power prices to be higher than pre-pandemic.”

(With assistance from Serene Cheong)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments