China, the highly problematic saviour of the global aluminium market? Andy Home

LONDON, April 18 (Reuters) – The shocks from the imposition of U.S. sanctions on Oleg Deripaska and his UC Rusal aluminium empire are still rolling through the market.

After Rio Tinto last week flagged it was declaring force majeure on some raw material contracts, it warned today of potential “adjustments” to its aluminium guidance this year due to the sanctions.

Some of Japan’s major trading houses, meanwhile, have asked Rusal to stop shipping aluminium for fear of secondary sanctions.

Japan imports around 300,000 tonnes of Russian aluminium every year, equivalent to around 16 percent of its total import needs.

Aluminium’s previously well-filled supply chain is starting to crack along multiple fault lines.

As supply fears grow, the market’s attention is turning to China as a potential source of aluminium.

There are almost a million tonnes of the stuff sitting in warehouses registered with the Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE). That metal will flow out of China if the price is right.

But China’s role as supplier of last resort is heavily laden with irony given the political push back against its exports of aluminium products.

The world’s largest producer is also suffering from its own supply-chain turbulence.

Opening the arbitrage window

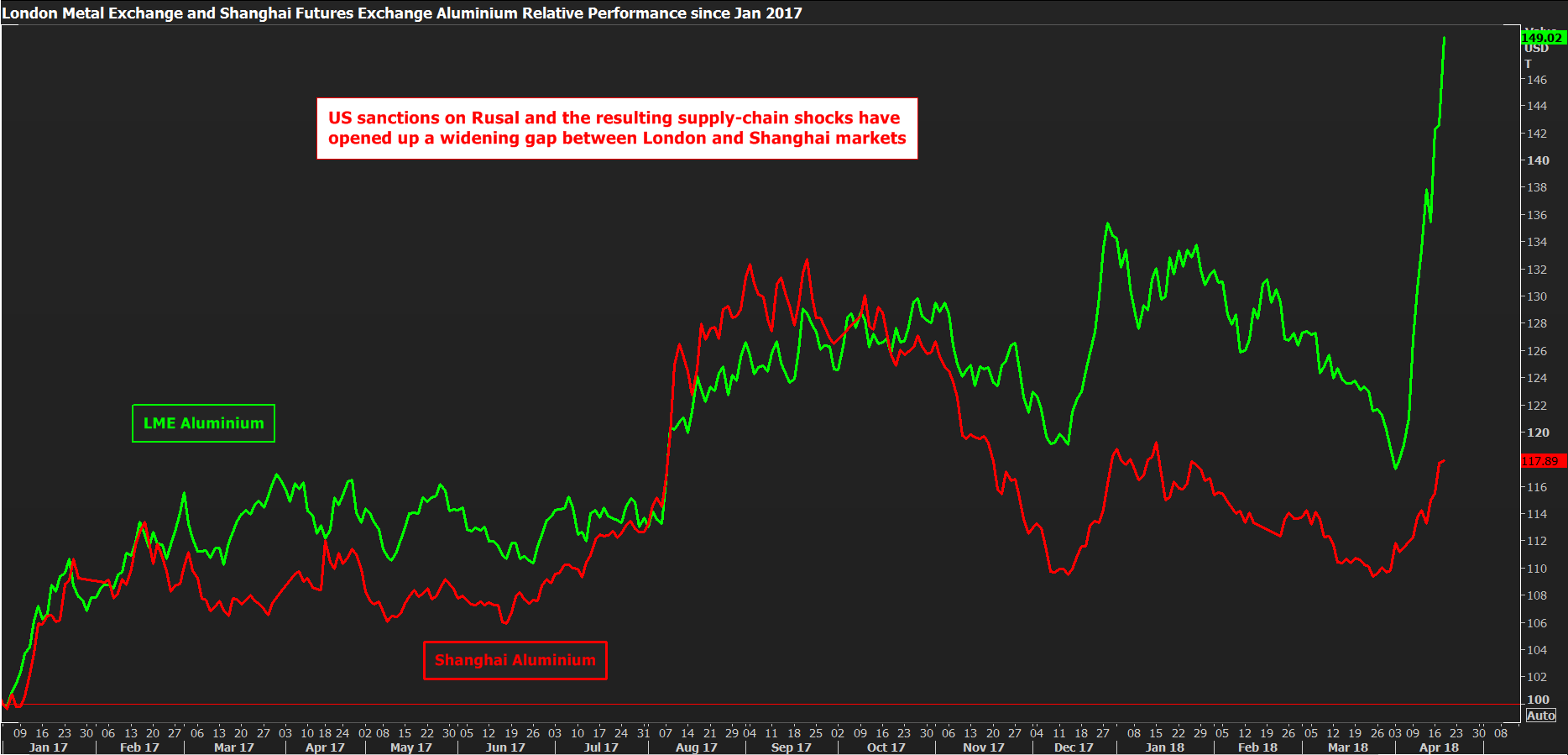

In London the price of aluminium has been on a rocket-propelled charge since the U.S. Treasury announced the sanctions on April 6.

At a current $2,527 per tonne London Metal Exchange (LME) three-month aluminium has gained over $500 in the space of under two weeks.

That has opened up a widening gap with Shanghai prices, which have reacted only mutedly to the excitement in London.

However, still higher prices will be needed for Chinese aluminium to leave the country and fill the supply gaps opening up in the rest of the world, according to analysts at CRU.

That’s because exports of primary metal from China are subject to a 15 percent export tax, unlike exports of products which qualify for VAT rebates.

Depending on market dynamics in both London and Shanghai, CRU is looking for prices to approach $3,000 to unlock the 991,780 tonnes of metal sitting in ShFE warehouses.

But this is what will be necessary if Rusal’s own exports out of Russia are blocked.

CRU was already anticipating a supply shortfall of around 1.8 million tonnes outside of China before the sanctions, according to CRU’s head of primary and products research, Eoin Dinsmore.

Throw in the potential loss of 200,000-230,000 tonnes of monthly exports from Russia and there would be “a critical need” for Chinese metal.

Goldman Sachs agrees, arguing that a complete cessation of Rusal exports could lift prices to as high as $3,200. (“Quantifying upside risks from Russian Sanctions”, April 18, 2018).

The bank’s view is that Rusal will be restructured to bypass sanctions and allow both production and exports to continue but it has still lifted its price forecasts to factor in the uncertainty.

Metal not products

The irony here is that China is already a huge exporter, not of primary aluminium but rather of aluminium in the form of semi-manufactured products.

Indeed, such has been the flood of products out of the country that up to now the big issue for everyone else has been how to stop China exporting so much not how to stimulate it to export more.

The United States has led the political push back against Chinese product exports, which rose another 4 percent last year to an annual record of 4.24 million tonnes.

President Donald Trump has signed off on a 10-percent import tax on all imports of aluminium with China firmly in the administration’s sights.

Separately, the United States is still slapping anti-dumping duties on specific Chinese products.

Aluminium foil has already been hit with swingeing countervailing duties and the net has just been widened to include aluminium alloy sheet.

This is the dilemma for the rest the world. It now desperately needs Chinese exports of primary metal to rebalance the market but simultaneously still needs lower exports of products.

Chinese turbulence

China’s own aluminium production sector, meanwhile, is experiencing plenty of its own turbulence.

The closure last year of “illegal” capacity, meaning that operating without all the correct permits, and mandated curtailments at some plants during the winter smog campaign have slowed production growth to just 0.3 percent in the first quarter of 2018.

It’s true that the winter heating season cuts have disappointed aluminium bulls.

But the environmental pressure on the aluminium smelting sector shows no signs of letting up any time soon.

Adding new uncertainty is a draft proposal from the National Development and Reform Commission targeting aluminium producers drawing their power from captive coal plants and stipulating retroactive power payments to the government.

Hongqiao, the world’s largest aluminium producer and one that is heavily reliant on coal, could be particularly vulnerable.

At this stage the proposal is no more than that and there is likely plenty of wriggle-room for such a big industrial powerhouse and employer.

But the key takeaway here is that Beijing’s scrutiny of its aluminium sector is only getting sharper as it targets both excessive capacity and polluting industries.

At any other time in recent history China’s giant smelter sector could have been relied upon to lift production in response to rocketing prices.

Right now, however, price is only part of a more complex landscape defined by “illegal” capacity closures, winter curtailments and, now, the longer-term viability of coal as a source of the power needed to produce the metal.

The price of excess

The global aluminium industry continues to pay the price of Chinese excess.

With over half of the world’s aluminium production concentrated in one country, there is no cushion outside of China to compensate for diminished flows of metal from Rusal.

Moreover, what is clearly available right now in China, namely the million tonnes sitting in Shanghai warehouses, is trapped behind China’s export tax.

What is flowing in ever increasing quantities out of China is in the wrong form for the rest of the world, which now needs more primary aluminium and less product.

This problematic reliance on China has been growing for many years but it’s taken the hit on the largest non-Chinese producer to expose the dysfunctional nature of the global aluminium supply chain.

(By Andy Home; Editing by Louise Heavens)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments