Cheaper solar in India prompts rethink for coal projects

India’s coal-power plant developers are growing more pessimistic about their projects after a plunge in the cost of electricity from solar panels improved the economics of renewable energy.

After a string of federal auctions, solar is suddenly the cheapest source of electricity in India. That’s darkening the outlook for the coal-fired power industry as projects struggle to find customers or face cancellation amid a glut of capacity.

“The crashing solar tariffs are creating a mental block for distribution companies and holding them back from signing long-term purchase agreements with conventional power producers,” said T. Adi Babu, chief operating officer for finance at Lanco Infratech Ltd., an Indian power producer. “A couple of years back, when people talked of solar reaching grid parity, people were skeptical. Now the solar tariffs have gone well below that. It is definitely making conventional players sit up and take notice.”

In May, the Business Standard reported that the state of Gujarat scrapped a so-called ultra-mega power project. Sujit Gulati, Gujarat’s additional chief secretary for energy and petrochemicals, didn’t respond to an email seeking comment. Uttar Pradesh ditched plans to buy long-term power supplies in favor of short-term purchases through the oversupplied spot power markets.

The solar auctions both advance Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s goal to reduce fossil-fuel pollution in a country that’s home to almost half of the world’s 30 most-polluted cities and throw into question the direction of India’s energy policy, which still envisions an expansion for coal power. For now, the government expects demand for traditional power plants will continue to rise, boosting demand for the most dirty fossil fuel.

“Coal-based capacities are facing competition, but we are not seeing them becoming irrelevant for some years to come and they will continue to serve the base-load demand,” said P.K. Pujari, secretary at the ministry of power. “The demand for thermal power is going to increase in absolute terms.”

Even so, evidence of a shift away from coal is gathering by the day.

- State-run NTPC Ltd., India’s largest power producer, along with RattanIndia Power Ltd. are considering installing solar panels over land initially intended for thermal projects.

- NTPC said in February it’s aiming to have 30 percent of its capacity come from non-fossil fuel by 2032

- The Indian subsidiary of Hong Kong-listed CLP Holdings Ltd., which owns both coal and renewable projects, is debating whether to participate in another round of conventional projects. “A transition from coal to solar is a generic direction that all utilities are taking. We are an early mover into the renewables space so our journey continues,” Mahesh Makhija, business-development director for renewables, said in a phone interview.

- The government of the sunny state of Rajasthan expects more conventional power to be replaced by clean energy as higher renewable purchase targets are fulfilled. “At the rate the renewable power tariffs are decreasing, the time is not far when renewable power will start replacing costlier conventional power,” Sanjay Malhotra, principal secretary for energy in the Rajasthan government, said by phone.

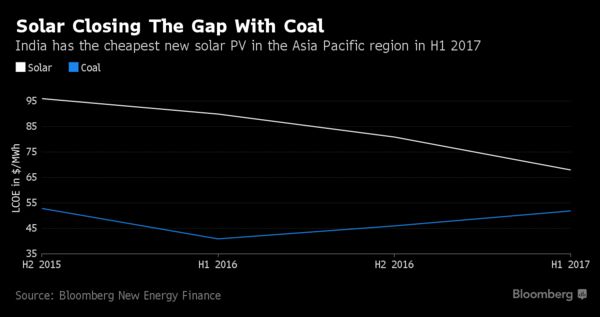

Solar is now as much as 50 percent cheaper than new coal power, according to solar research firm Bridge to India.

“That’s why we have seen many new coal power tenders being suspended or canceled in the last three months,” said Vinay Rustagi, managing director at Bridge to India.

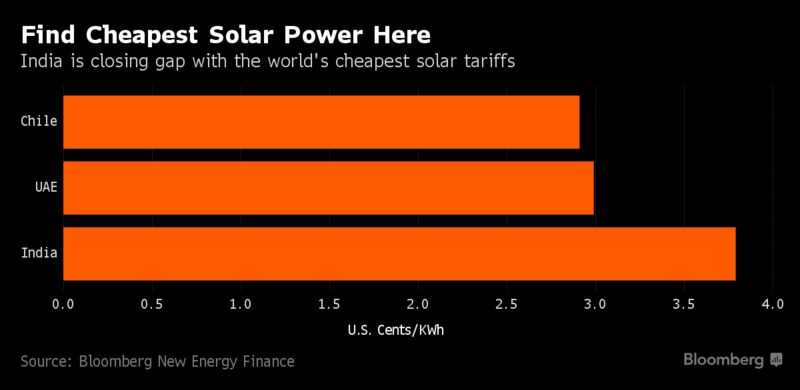

Last month, companies including SoftBank Group Corp. of Japan and India’s Bharti Enterprises Pvt. offered to supply solar electricity for 2.44 rupees (3.8 U.S. cents) a kilowatt-hour, a price competitive with market rates and with power from coal plants.

The price is within striking distance of the lowest recorded bids for solar in the United Arab Emirates and Chile, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

“There is no doubt that conventional power producers need to be more efficient,” said Ashok Khurana, director general at the Association of Power Producers, a lobby group of non-state power generators. “The national electricity policy says that power distributors buy the most competitive electricity, so to survive they have to become efficient.”

While solar energy becomes cheaper, the cost of coal power is rising in India. It’s becoming more costly to mine at home and faces tougher environmental regulations, BNEF said in a report. Low demand is also an issue.

The levelized cost of energy from a new super-critical coal plant in India stands at 3,541 rupees a megawatt-hour, or 3.54 rupees a kilowatt-hour, meaning it’s above the 2.44 rupees a kilowatt-hour achieved at the recent auction, according to BNEF. The cost of new emissions rules increases the cost of new coal plants further to 3,890 rupees a megawatt-hour, or 3.9 rupees a kilowatt-hour, BNEF said.

“Energy system planners, utilities and investors are all looking at the rapid changes in the Indian electricity system landscape and re-evaluating assumptions that were entirely sensible 2-3 years ago, but outdated and wrong today – or at least will be within the medium term,” Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said by email.

At the recent auction prices, the solar tariff is even lower than the average electricity spot price of 2.77 rupees in April on the Indian Energy Exchange Ltd., the country’s biggest power exchange.

“Such low solar prices will not allow power rates to spike above these levels and will create a better market,” Rajesh K. Mediratta, a director at the exchange, said in a phone interview.

Not all the coal developers expect the solar boom to last. Some are wary about pushing into the industry, saying the new tariffs don’t make economic sense and aren’t sustainable.

“I have a feeling we will see a big crash in the solar industry in times to come,” said Sanjay Sagar, chief executive officer at JSW Energy Ltd., a developer of coal- and gas-fired power projects.

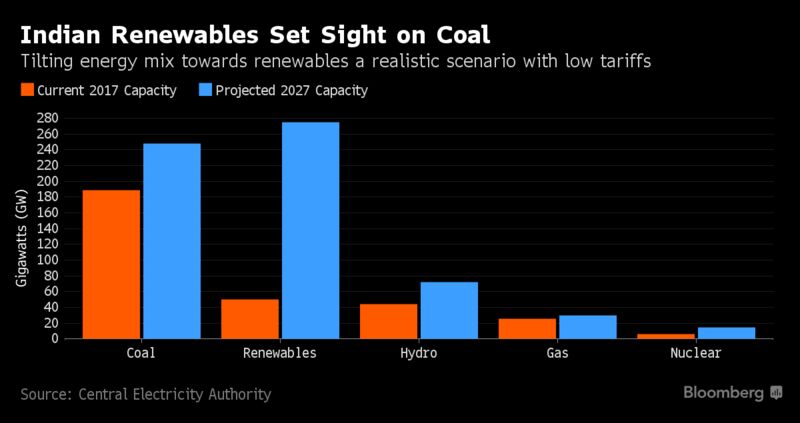

Even so, renewables are expanding quickly in India. Solar capacity has surged fourfold since December 2014 to about 12 gigawatts, while wind farms now provide 32 gigawatts, up from 22.5 gigawatts over the same period. Modi is seeking an additional 88 gigawatts of solar and 28 gigawatts more of wind by 2022. And those projects are crowding coal out of the power market.

“When the renewable generation is available, to that extent the thermal generation goes off the grid,” Ravindra Kumar Verma, chairman of India’s Central Electricity Authority said in an interview in New Delhi, adding that the country doesn’t need any more coal-fired capacity beyond what exists or is already under construction.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments