Brent Cook: Quinton is a geologist who can see the big picture. He focuses on how a mineral deposit forms and assesses if it is economic. His contributions allow us to cover a lot more ground in the same time and our discussions often refine and improve the final investment decisions. It’s a whole aspect to the business that’s going to help me make Exploration Insights better. Given the state of the junior mining sector, this is the time to be picking up the deposits and companies that are undervalued or that show potential value based on a real economic evaluation.

“Because this is such a high-risk game, we’re mostly looking for homeruns.”

Quinton came out of Newmont Mining Corp. (NEM:NYSE) and Newcrest Mining Ltd. (NCM:ASX). He knows how the big companies work and what their investment criteria are. Ultimately, our goal at Exploration Insights is to identify deposits that are going to have high enough margins and be large enough to attract a buyout or purchase from a major mining company. Quinton did that at Newmont.

TGR: You and Quinton will be in San Francisco on Friday, Nov. 16 for the San Francisco Hard Assets Conference to lead the workshop for investors, “Geo Tips for Tenbagger Investments,” sponsored by The Gold Report. What’s the name of the last tenbagger in the Exploration Insights portfolio?

BC: Well, I obviously wish there were more, however, since starting Exploration Insights in 2008 we have scored big on companies like Mirasol Resources Ltd. (MRZ:TSX.V), AuEx Ventures Inc., Fronteer Gold Inc., Kaminak Gold Corp. (KAM:TSX.V), and more recently Reservoir Minerals Inc. (RMC:TSX.V) and GoldQuest Mining Corp. (GQC:TSX.V).

TGR: Do you have a target rate of return when you invest in companies?

BC: In a sense we do. It all comes down to what a company is looking for, what that mineral deposit really looks like and, if it’s successful, what it’s worth. How much is it going to take to turn this rock into money? That takes into account the development costs, capital expenditures, and process and infrastructure costs. It all goes into determining what we need to see on a property. It’s on a property-by-property, country-by-country basis. That’s how we get a sense of what our target price might be. Then we follow the news as it goes along and judge if we should stay in it, buy more or sell.

“You cannot judge a deposit or a drill intersection based on the grade.”

Because this is such a high-risk game, we’re mostly looking for homeruns. We do own a number of prospect generators that just plod along and go up and down a little bit with the market, but that’s a different business model. I think we still have a chance for a tenbagger in those, but it’s a long-term investment.

TGR: Quinton, one of the things that you’re going to talk about at the workshop is red flags in mining company press releases. Give us some specifics that make you raise your eyebrows.

Quinton Hennigh: Let’s say there’s a news release that comes out. It mentions a killer hole—a long interval for a potentially good grade. But the company doesn’t list a cross section, making it very difficult to interpret. That’s always a little suspect. Why isn’t it showing us the full picture here?

Grade smearing is a chronic problem. Grade smearing is where a company takes a high-grade interval or two and transposes that into a much longer interval of lower grades in order to make it look like a bulk intercept.

Then there is drilling where there was a previous campaign. Maybe a major had a property and did some drilling. It got some results. Now a junior is coming back in and drilling basically on top of that and reporting results as if it’s a new discovery. The company isn’t showing the historic information and allowing investors to gauge what it actually has in its proper context.

TGR: The difference between true width and apparent drill width in drill results is also on the agenda. Why do investors need to know the difference between those two things?

QH: There’s a lot that goes into interpreting the geometry of a deposit. Drill intercepts are never a simple line. We have a one-dimensional line of data. Deposits are not one-dimensional. They’re three-dimensional. We need multiple holes to see what’s going on. You can’t say much about geometry until you have multiple intercepts.

“The advantage of Nevada is that all the infrastructure is there.”

True width is the width of an intersection or a vein that gives us one of the three dimensions we need to determine the tons of a deposit or a system. We need true width versus apparent width or drill width, which can give us an exaggerated width.

TGR: Brent, you’ve said in other interviews that a 1 gram per ton gold (g/t) deposit could be economic in Nevada whereas a 2 g/t gold deposit might be uneconomic elsewhere. Other than the fact that you have walked over most of it, why are you partial to Nevada?

BC: The real point of that statement is that you cannot judge a deposit or a drill intersection based on the grade. It has to be viewed in the context of what it costs to get the gold out of the rock. There are certain types of deposits that average 1 g/t in Nevada that you can make tons of money on because they’re so cheap to process and recover the gold. There are other deposits of 1 g/t that would not be economic anywhere; it’s all about the costs of turning that rock into money.

The advantage of Nevada is that all the infrastructure is there. A 1 g/t deposit makes money in Nevada, but the same deposit out in the middle of Burkina Faso will have infrastructure costs that are much higher. Then add in processing costs that are going to be more, plus energy costs and a host of other issues and it is clear we are not dealing with the same base case scenario. Jurisdiction and location relative to infrastructure are also key components of determining what a deposit is actual going to be worth.

TGR: Absolutely. What are some companies you are following in Nevada?

QH: The more exciting story at present is Gold Standard Ventures Corp. (GSV:TSX.V; GDVXF:OTCQX). It has a program on the south end of the Carlin Trend that’s an extension of the Rain mine, an old Newmont mine. It has been drilling blind targets based on geophysics and coming out with very good results. The system is complex—some holes hit, some holes don’t. It’s one of the more exciting stories right now. We no longer own it but it is certainly high on my radar screen.

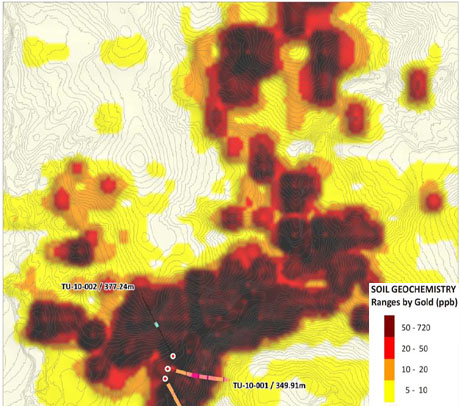

Gold Standard is not alone though. There are other projects out there. For instance, Pilot Gold Inc. (PLG:TSX) is drilling at Kinsley Mountain, which is an old gold mine that is seeing new interest due to higher gold prices. The technical team at Pilot put together the genetic model that delineated the nearby Long Canyon gold deposit and they are now developing some new concepts to test at Kinsley.

Miranda Gold Corp. (MAD:TSX.V) is a very good story. It has a lot of joint ventures and exposure to good properties. CEO Ken Cunningham is a first-rate geologist and knows how to pick projects.

NuLegacy Gold Corp. (NUG:TSX.V) is doing some very interesting work south of the new discovery that Barrick Gold Corp. (ABX:TSX; ABX:NYSE) has at Goldrush. The Goldrush project looks as if it’s going to be a substantial discovery of more than 10 million ounces. Barrick is actively drilling it right now. NuLegacy is targeting a similar zone on its project about five miles south.

TGR: There’s been a lot of development in Nevada over the years, but it seems most of these projects are proximate to other producing assets. Is that part of your investment thesis?

TGR: There’s been a lot of development in Nevada over the years, but it seems most of these projects are proximate to other producing assets. Is that part of your investment thesis?

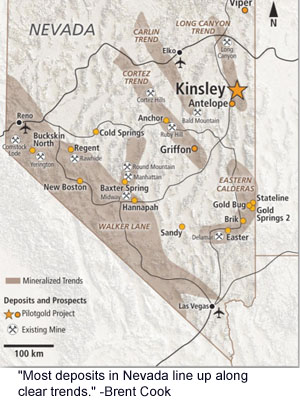

BC: Most of these deposits in Nevada line up along clear trends. These trends represent deep structures into the earth’s crust that are the conduit to mineralization. That’s where you go to look. We certainly want our investment thesis to make sense in the context of the basement geology throughout Nevada, or anywhere around the world for that matter.

TGR: You stay with a small number of companies for the newsletter. You have a very specific thesis. But in a recent edition, you said you were going to get into some other types of plays.

BC: Given the current currency debasement from quantitative easing, the speculative money is going to jump back into these sorts of plays very selectively. We decided it was time to get a bit more aggressive in early-stage exploration. Having said that, we bought a big company that Quinton identified but nixed two other much smaller companies that we initially had high hopes for being worthy of our clients’ money. Although we want to get aggressive, we’re not getting careless. I still feel the market is not going to buy your mistakes.

Our thesis is the same, though. I still want to keep it to 20 companies or fewer. A few stocks in the EI portfolio really don’t count as exploration stocks. Prospect generators are a different business philosophy and risk profile, for instance. If I bring something in, I want to be able to throw something out as well. That allows me to continually upgrade the portfolio. But exploration takes a bit of time. It’s a process. I’m not going to throw out a company until I’ve seen it follow through with the process and our original investment thesis has been tested. However, I am looking to upgrade the portfolio as quickly as possible.

TGR: You just have these 20 companies. How do your readers feel about that?

BC: They seem to be pretty happy with that. When I worked at Global Resources, the biggest problem I saw—and I still hear this from various subscribers and others out there—is that they’ve got a list of 100 companies, but they have no idea why they bought them, what they’re worth or what to expect. That’s a real problem and headache in this sector for retail investors. They hear that they should buy something for whatever reason and then they forget why they bought it and watch it slowly go down.

TGR: You’ve said that the odds of a geochemical anomaly becoming an economic deposit are roughly 10,000 to 1. Nonetheless, hundreds of millions of dollars are raised each year with those odds in place. Is the system broken? Or are enough people making money on the way up that it doesn’t matter what happens on the way down?

BC: It’s not broken, but it’s certainly inefficient. The scientific side of exploration often doesn’t understand the money side and the money side doesn’t usually understand the scientific process. A lot of money gets wasted through unrealistic expectations on both sides. It’s much easier to raise money on an old property, as Quinton mentioned, that’s got an old drill hole in it from years ago. They say, “Look, they drilled this hole. It was 100 meters at 2 g/t. We can repeat this. Maybe it gets bigger?” And, a money guy can say, “Yeah, I can see where we can repeat this hole. We get some excitement. I get off my paper in four months and I can move on.” A lot of money gets wasted with that thinking and more often than not retail investors get stuck, if they haven’t done their due diligence.

TGR: Is that wasted money coming home to roost now? Canaccord is shutting down a number of offices and the brokerage community is struggling in general.

BC: Most definitely. A lot of hedge funds that bought into these two years ago didn’t understand the long odds of success and how to evaluate early-stage concepts or the people behind them. Now they’re stuck with some stock that’s down by half, or more in some cases, with no liquidity. It’s a real problem. It’s very difficult to raise new money on anything but the very highest quality drill holes or prospects right now. I believe that’s going to last through this year at least.

TGR: The TSX Venture Exchange recently changed its regulations to allow companies to finance at less than $0.05 a share. What are your thoughts on that, Quinton?

QH: It’s like a stimulus for juniors. It’s going to amount to an excessive amount of paper being issued. Junior companies are going to have to issue a lot of it to raise anything meaningful. A first-class drill program can cost $1.5–3 million (M) in a reasonable location. That’s a lot of nickels. We’re going to be like Australian companies with a few billion shares out pretty quickly.

TGR: Are there some other companies that you want to tell us about today?

BC: The prospect generator model is a business model employed by some juniors that recognize the long and poor odds of success. It focuses on generating good conceptual ideas that can then be brought to another company with more money to spend to test the exploration thesis. It’s a very intelligent way to efficiently explore and make money, but it’s slower and not as exciting as the big go-for-broke drill hole play.

The bottom line is that we’re investing in ideas, the intellectual capital of the people in the company. If I’m an investor in a company’s intellectual capital, I want to keep my percentage of that as high as possible and dilute my interest at the project level, which is the drilling level. That way I get many more shots at potential discovery over time without excessive share dilution.

TGR: Have you ever done any quantitative analysis between prospect generator companies and the typical capital pool company method?

BC: No, but my experience has been that the prospect generators are less volatile and they last longer. Ultimately, I’ve made more money off of those than the occasional homerun because they go through a number of projects—10, 15, 20 of their projects drilled by partners that eventually fail—that is the reality of exploration. Eventually, however, they seem to come up with a project that they recognize as being special. They know that because the more work they do, the better it gets. Many of them will keep that project for themselves. Then we own a company that has 100% of a project that is recognized as special and we have not been diluted out of the discovery by previous failed exploration efforts. We’ve got something that really works.

The examples are Mirasol Resources, Kaminak Gold, Virginia Mines Inc. (VGQ:TSX) and AuEx Ventures. They have been huge homeruns, but it took time for them to get to the stage where they recognized the project was good enough to take on their own.

TGR: Do you have anything to add to that, Quinton?

QH: Project generators tend to be run by people who have a prospecting mentality. These are good geologists who can see the big picture. They can recognize the potential of a region. They can go in and pick up areas that are clearly geologically important. A lot of people that we know in the companies that Brent just mentioned know what they’re doing and know the areas that work and pick up that land. That alone tells you that they’re a pretty good bet.

TGR: Almaden Minerals Ltd. (AMM:TSX; AAU:NYSE) is a good example of a prospect generator.

BC: Almaden has been around for over a decade now. The company only has about 59M shares out. It has about $20M in the bank, which it got by selling stock in companies that ventured into its projects or selling projects to somebody else, not by issuing shares. It finally came across Ixtaca in Mexico, which was better than average and continues to be better than average. The stock has done fairly well. It’s drilling out a project that offers homerun potential and it’s doing it effectively and efficiently. That’s how the prospect generator model works.

TGR: The projects are longer-term investments, right? You have to be willing to hold these for a while.

BC: Exploration is really a long-term scientific process where we test a thesis, go back to the drawing board, test it again. It’s a process. Companies don’t just go out there, drill a hole, and say, “Bang! That was easy. Let’s go out and drill another one!”

TGR: Are you recommending to your readers that they should stay out of most of the names in the junior mining business until tax-loss selling season is over?

BC: There’s going to be a lot of pressure on these juniors coming into the end of the year. It’s been going for quite a while; we’ve seen a reprieve, but there are a lot of funds that have to get liquid and get rid of this stuff before the end of the year so they can start new and work on their bonuses for the next year. There’s going to be a lot of pressure. There’s no urgency to chase things up unless there’s an obvious drill-hole discovery in the making.

TGR: Quinton, do you have anything that you want to add?

QH: Things do seem to be picking up, but we’re going to see continued volatility. Looking back on the past two years, one thing that stands out in my memory is that companies were issuing paper in a big way when things were riding high. There’s a lot of overhang from that period. There are warrants out there. Funds are looking to liquidate certain positions just to get out of them. We’re not out of the woods yet.

TGR: Thanks for your time, gentlemen.

Brent Cook and Quinton Hennigh will be teaming up with fellow geology experts Chris Wilson and Andrew Tunningley from Exploration Alliance S.A. to present a special geology and mining education seminar called Geo Tips for Tenbagger Investments: A Streetwise Reports Seminar. It will be offered as part of the Premium Education Program at the San Francisco Hard Assets Conference on Friday, Nov. 16 from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. In this exclusive seminar, you’ll find out how savvy investors spot the 2% of mining discoveries that can become wildly profitable, and how to spot the hidden clues inside mining company press releases. Learn how to recognize tenbagger opportunities from these experts using the most innovative geology and mining concepts. If you are registered for this event, you may submit your questions or topic suggestions here to be addressed during the seminar. This is expected to sell out, so reserve your seat now.

Brent Cook brings more than 30 years of experience to his role as a geologist, consultant and investment adviser. His knowledge spans all areas of the mining business, from the conceptual stage through detailed technical and financial modeling related to mine development and production. Cook’s weekly Exploration Insights newsletter focuses on early discovery, high-reward opportunities, primarily among junior mining and exploration companies.

Dr. Quinton Hennigh recently joined Exploration Insights where he provides geological expertise reviewing companies, projects and activity in the junior mining space. He began his career as an economic geologist with large mining companies including Newmont Mining Corp., Newcrest Mining, and Homestake Mining, where for 15 years he managed exploration projects in North America, Europe, Australia, Asia and South America. In 2007, he joined the junior gold sector where he has held executive and advisory roles at Gold Canyon Resources, Novo Resources Corp., Euromax Resources, Prosperity Goldfields and Evolving Gold Corp. He earned a Master of Science degree and a Ph.D. in geology and geochemistry from the Colorado School of Mines in 1993 and 1996, respectively.

Want to read more exclusive Gold Report interviews like this? Sign up for our free e-newsletter, and you’ll learn when new articles have been published. To see a list of recent interviews with industry analysts and commentators, visit our Exclusive Interviews page.

DISCLOSURE:

1) Brian Sylvester of The Gold Report conducted this interview. He personally and/or his family own shares of the following companies mentioned in this interview: None.

2) The following companies mentioned in the interview are sponsors of The Gold Report: Gold Standard Ventures Corp., Pilot Gold Inc. and Almaden Minerals Ltd. Streetwise Reports does not accept stock in exchange for services. Interviews are edited for clarity.

3) Brent Cook: I personally and/or my family own shares of the following companies mentioned in this interview: Mirasol Resources Ltd., Reservoir Minerals Inc., Almaden Minerals Ltd. and Miranda Gold Corp. I personally and/or my family am paid by the following companies mentioned in this interview: None. I was not paid by Streetwise Reports for participating in this interview.

4) Quinton Hennigh: I personally and/or my family own shares of the following companies mentioned in this interview: None. I personally and/or my family am paid by the following companies mentioned in this interview: None. I was not paid by Streetwise Reports for participating in this interview.

Comments