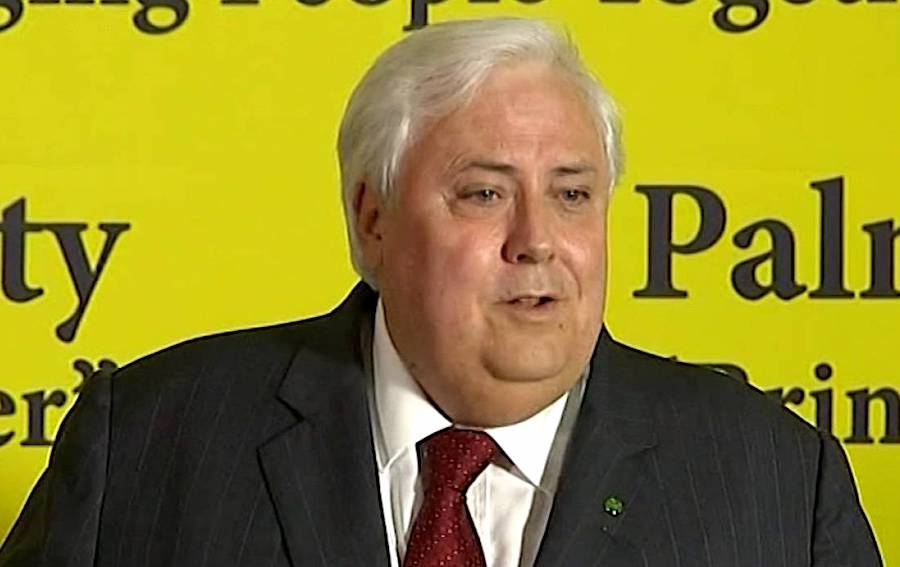

The brash billionaire who wants to make Australia great again

Half a world from the White House, another big-talking billionaire wants to make his country great again.

Clive Palmer, who made his fortune in mining, is running for the Senate on his right-of-center United Australia Party ticket. Billboards of his smiling face and raised thumbs are spread across the country in advance of next month’s election.

The 65-year-old, whose last foray into politics saw his party implode amid infighting and acrimony, has spent more than $30 million — a significant sum in a country with a population less than 25 million — attempting to win influence with an agenda that includes slashing taxes and doing more to tap Australia’s mineral wealth.

While he’s nowhere near as popular as Donald Trump — polls show he’s unlikely to win any lower house seats — Palmer has enough support to influence the crucial swing state of Queensland

While he’s nowhere near as popular as Donald Trump — polls show he’s unlikely to win any lower house seats — Palmer has enough support to influence the crucial swing state of Queensland. The Australian Financial Review reported Thursday that he struck an alliance with Prime Minister Scott Morrison to work together under Australia’s preferential voting system, a move that could hurt the opposition Labor party’s chances of taking power if the race tightens over the coming three weeks.

Palmer rejects comparisons with the U.S. president, boasting of the large swing that catapulted him into federal parliament in 2013. “Donald Trump didn’t start to do anything for three or four years later,” he said from Brisbane on Australia’s northeast coast.

Like other populist politicians, Palmer is tapping into a deep vein of disaffection with the mainstream parties in Australia, where many voters feel left behind despite almost 28 years of uninterrupted economic growth. As a senator, Palmer would join a group of minor parties and independents likely to hold the balance of power in the upper house and wield an outsized influence on the legislative agenda.

Palmer turned to politics after collecting assets across Australia and his advertising blitz threatens to eclipse the government and Labor. Hundreds of yellow “Make Australia Great” billboards have popped up across the country, while advertisements have flooded television screens. He wants to run candidates in all 151 lower house seats.

In a country where vocal ambition doesn’t always earn praise, Palmer’s brashness and bold talk make him a target for criticism. Rival populist Pauline Hanson has said the billionaire was only in it for himself, while Anthony Albanese, a Labor member of Parliament, called Palmer’s previous political stint a “debacle.”

He served just one term as the Palmer United Party’s sole lawmaker in the lower house. Two of his three senators in the upper house defected and the party was de-registered in 2017 — only to be revived as the United Australia Party last year.

“I’ve never had any pressure on me,” Palmer said. “It’s perceived pressure.”

Palmer’s political ambitions are bankrolled by a fortune that the Bloomberg Billionaires Index values at more than $1 billion.

His biggest payday came in 2006 when Chinese company CITIC Pacific gave him $415 million for the right to mine his patch of the Australian outback. Palmer, who initially made money in real estate, held the resources rights since the 1980s.

An Australian court awarded him a further $150 million last year following a long-running fight over royalties from the CITIC iron ore mine. Future payments will vary based on production and commodity prices, but annual checks of about $200 million, stretching to as much as $500 million in five years, are expected.

“You create wealth by being different to other people, but I’ve lost a bit of the motivation. At my age there doesn’t seem much need to make much more money” —Palmer

Untapped coal and cobalt assets could add to his net worth. Then there’s his Gold Coast housing development plans and an island resort in the Pacific.

“You create wealth by being different to other people,” Palmer said of his investing philosophy. “But I’ve lost a bit of the motivation. At my age there doesn’t seem much need to make much more money.”

Doubt remains about whether some of his plans will happen, including a full-scale working replica of the Titanic.

Palmer said it’s disappointing that the Titanic II has taken so long to build. The ship’s maiden voyage has been pushed back to around 2022 from its original date of 2016.

“It’s something you wouldn’t want to do if you realized how detailed it was,” he said. “But I’m confident we’ll go ahead with it. As long as I keep getting plenty of money, we can do it.”

(By Andrew Heathcote and Edward Johnson)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments