BHP should stand pat on copper — opinion

All major miners agree that copper has a bright future. The trouble is how to get at it.

Take BHP Group, set to be the world’s biggest producer this year after Freeport-McMoRan Inc. sold down its stake in Indonesia’s Grasberg mine. Costs at BHP’s massive Escondida pit in Chile, which accounts for about one in 20 tons of copper mined globally, keep on disappointing. They’ll rise from the current $1.14 a pound to a range of $1.20 to $1.35/lb next year, the miner said in annual results Tuesday, well above its ambitions to keep them shy of $1.15/lb.

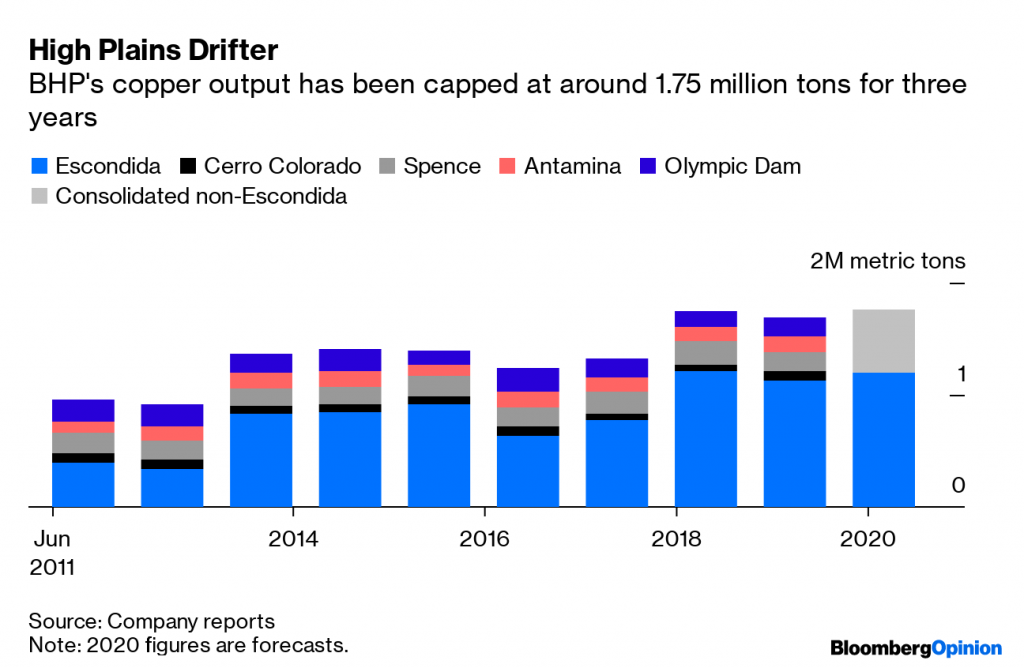

When the copper price is trading close to three-year lows at $2.61/lb, that still makes for a pretty profitable business. But with production for the whole copper business seemingly capped at around 1.75 million metric tons a year, it isn’t clear where volume growth will come from.

Miners love copper because it’s seen as a way to make a bet on a clean-energy future. Electric cars contain between four and 10 times as much copper as conventional ones, and wind and solar generators are forecast to consume 813,000 tons annually by 2027. It’s not clear that projects currently in the pipeline will be sufficient to produce enough metal to keep the market supplied once those sources of demand start ramping up around the middle of the next decade.

BHP’s main expansion at the moment is an extension of its Spence mine in Chile, which is set to go into production by December next year. That should add about 185,000 tons of annual production – barely enough to offset the the gradual exhaustion of the Cerro Colorado and Antamina pits, which have less than a decade of reserve life left in them.

Beyond that is the potentially massive, geologically difficult expansion of South Australia’s Olympic Dam mine. That pit has long been a challenge. Its significant uranium content would make BHP a major and low-cost producer of the atomic fuel. The risk, though, is that such a large influx of supply would crash the uranium oxide market and weaken the high-stakes economics of the project itself.

In theory, there ought to be interesting opportunities for M&A in the current environment. Freeport, for instance, could almost double BHP’s copper production, and has a lot less political risk attached now the long tussle with Jakarta over Grasberg is over.

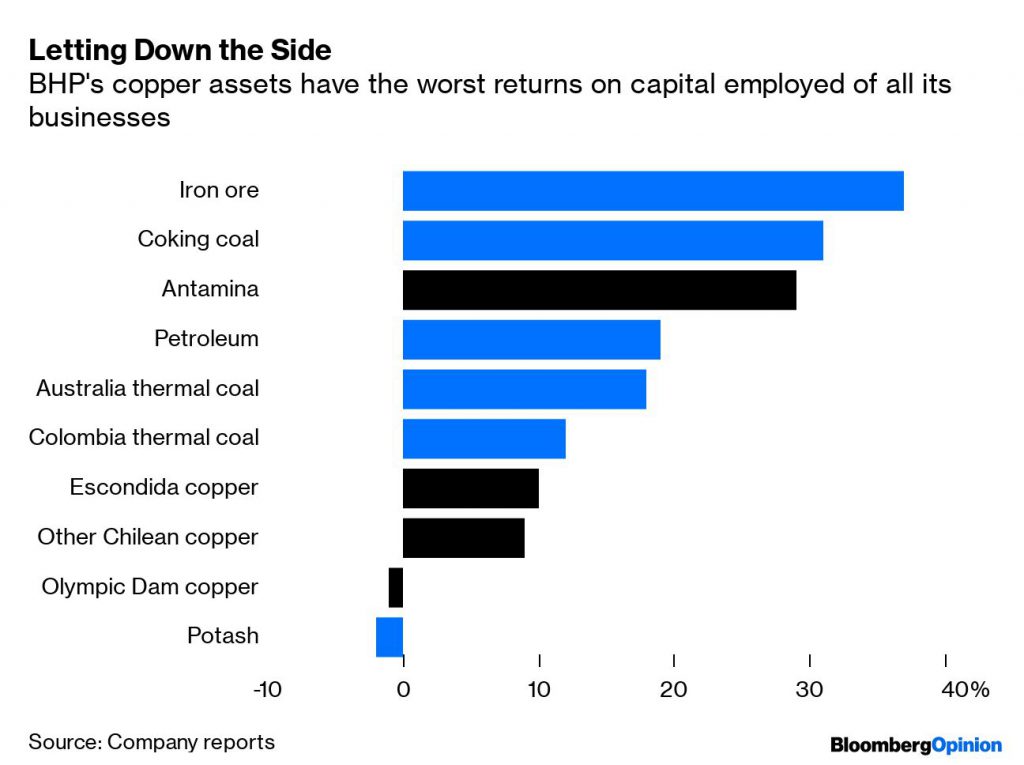

With return on capital employed of about 11%, it’s outperforming the underlying 6% return in BHP’s copper business and could be bought for about nine months’ cashflow. But with Elliott Management Corp. still a lingering presence on the shareholder register, management are unlikely to want to do anything too splashy.

Indeed, BHP’s rivals are prime examples of the risks that can be run from being too bold around copper. Rio Tinto Group’s Oyu Tolgoi mine in Mongolia could cost as much as $1.9 billion morethan forecast, with first production from the expanded project delayed until the middle of 2023, the company said last month. Glencore Plc this month announced plans to shut its Mutanda copper mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo due to rising costs and weak pricing for cobalt, an important by-product from the operation.

There may be a lesson in that. For all the billions BHP has spent on copper over the past decade, its returns from the red metal are still among the worst in the group. Rather than chasing volume, it might be better off watching the pennies, letting the market tighten and hoping prices rise to justify the money that’s already been spent. When the cards on the table look weak, there are worse things to do than just stand pat.

(By David Fickling)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments