BHP overstayed in petroleum — time to exit

BHP Group’s future can do without hydrocarbons.

The world’s largest digger is among the last heavyweights to mix mines with a significant presence in oil, a combination that is becoming harder to justify over the long term. Crude demand will be slow to recover after a pandemic that has kept workers home and jets grounded, and some of that appetite will never come back.

Meanwhile, pressure to cut carbon emissions is only increasing. Oil giant BP Plc is the latest to take a hit, warning it expects impairments and write-offs worth as much as $17.5 billion due to a more gloomy view of what lies ahead. The Big Australian could benefit from a dose of that realism.

Rival Rio Tinto Group offloaded its last coal mine in 2018, wrapping up a process that began in 2013

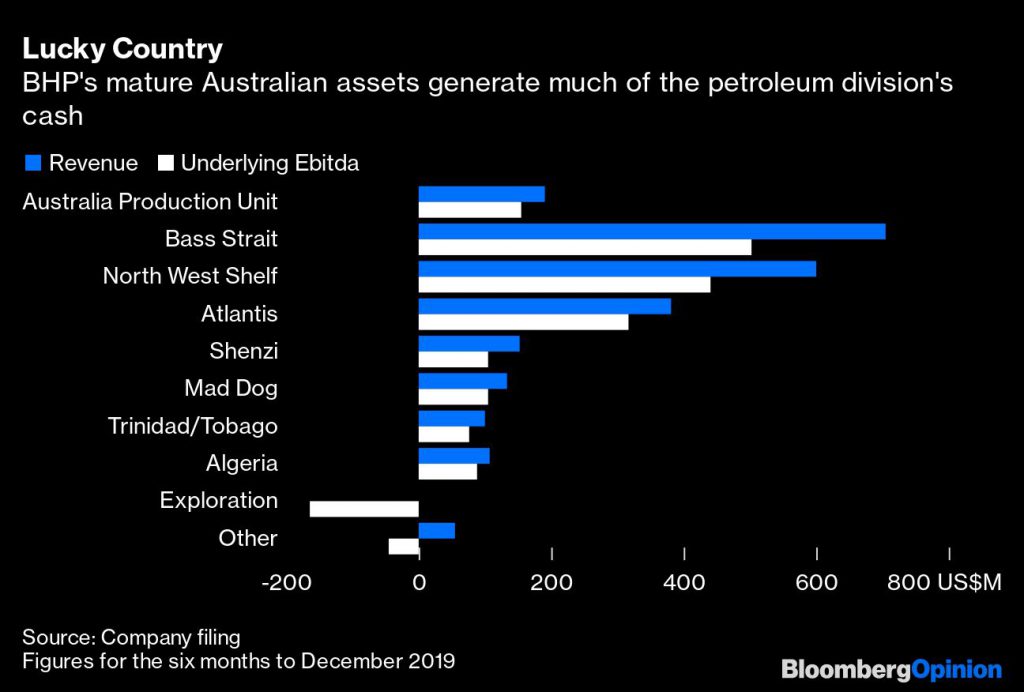

There is little question that the petroleum division, with assets from Western Australia to the Gulf of Mexico, has generated impressive cash over the years — if you exclude the ill-considered foray into U.S. shale, a $20 billion investment (excluding capital expenditure) much criticized by activist fund Elliott Management Corp. and eventually sold off in 2018.

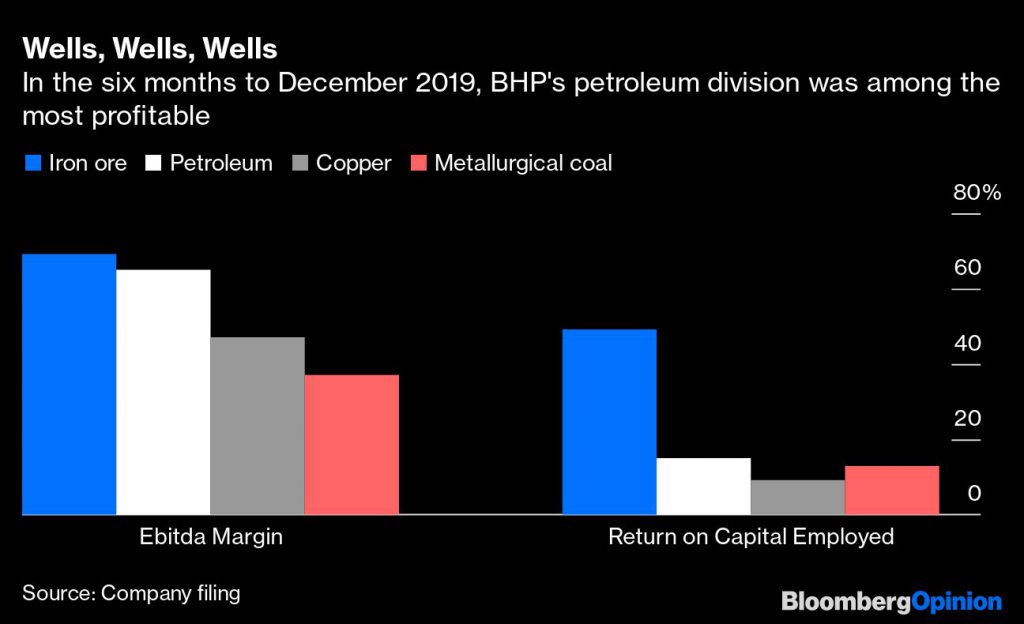

In the six months to December 2019, the unit accounted for about 13% of BHP’s total earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization, notching up an impressive 65% margin. Only iron ore, the group’s top earner, was higher, at 69%. Add in low production costs that cushion the blow of 2020’s lackluster oil prices, and it’s easy to see why putting in more cash is tempting when, as analyst Glyn Lawcock of UBS Group AG points out, the miner has few readily available alternative investments.

It’s also true that while the medium-term global appetite for oil looks far less certain than it did, there’s a more appealing argument to be made around fading supply. Indeed, the $115 billion miner’s central expectation last year of demand hitting a high point in the mid-2030s now looks bullish, compared to comments from the likes of Royal Dutch Shell Plc and BP.

A peak even in the middle of this decade, BHP’s low-demand scenario, may prove optimistic. On the production side, though, the miner is right to point out that the industry has been investing less, a trend that will only accelerate after a disastrous 2020 and squeeze future production. BHP has estimated ongoing natural field decline at a rate of 3% to 5% per year.

None of this means boss Mike Henry and his team can afford to ignore the signs that this year will prove to be a turning point for oil.

Diversification has benefits, but operating synergies between oil and mining are debatable — it’s not an accident that while majors sold out of one or the other, none have returned. As a standalone business, the petroleum division might arguably have ventured less enthusiastically into shale. And the risk today is clear: Staying on can turn into overstaying.

Here, Henry can reflect on the experience in thermal coal, where BHP woke up too late. Rival Rio Tinto Group offloaded its last coal mine in 2018, wrapping up a process that began in 2013. BHP held on to decent assets, using up tax losses. It’s now trying to retreat just as Anglo American Plc prepares to hive off its South African coal mines, and interest in the dirty fuel has dwindled. Oil has fewer easy substitutes, but it’s conceivable that, with significant changes in policy, crude could be left similarly stranded.

Accepting the need for an exit from a business that BHP has been in since the 1960s is only the first step, of course. For one, a carve-out in the mold of coal-to-aluminium producer South32 Ltd., which BHP spun off successfully in 2015, is harder to advocate for oil. The move then was about getting more out of sub-scale operations. In petroleum, BHP is not the operator for many of the assets, making such efficiencies harder to accomplish.

BHP can begin by reviewing its portfolio, starting with mature assets in Australia. Partner Exxon Mobil Corp. has said that it’s seeking a buyer for its share of the Gippsland Basin oil and gas development in the Bass Strait; a joint sale with BHP has been considered before. Chevron Corp., meanwhile, has put its stake in the giant North West Shelf liquefied natural gas venture on the block. That operation, Australia’s largest LNG project, is shifting from processing its own gas to opening services to new suppliers, a business known as tolling — less suited to either Chevron or BHP. The mining giant has in any event been less enthusiastic about gas than oil.

Granted, even that won’t be easy. Australia churns up a decent amount of revenue, and BHP can argue it is better to continue taking cash now, at the risk of selling for less later. Some investors may agree. A similarly short-term view in the Gulf of Mexico could see it adding to the portfolio as distressed rivals are forced out.

For newish boss Henry, though, none of those would look like the decisions of a company preparing for a greener future. He has an opportunity to outline the path to net zero emissions when BHP announces full-year results in August. An exit plan for oil would be one decisive step toward that goal.

(By Clara Ferreira Marques)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments