Banks shying away from fossil fuels bolster private credit deals

Private credit managers are doing significantly more fossil-fuel deals now than just a few years ago, as they step into a void left by banks exiting assets they worry pose too big a climate risk.

The value of private credit deals in the oil and gas industry topped $9 billion in the 24 months through 2023, up from $450 million arranged in the preceding two years, according to data provided by Preqin, an analytics company that tracks the alternative investment industry. That’s based on the limited pool of deals reported publicly or disclosed directly to Preqin.

The figures offer the clearest signal yet that fossil-fuel exclusion policies among banks — driven by regulatory and reputational concerns — are shifting some oil, gas and coal assets to less transparent corners of the market. It’s a trend that investors say is only going to increase in the coming years.

The expectation is that some banks “will just exit” the loans market for coal, oil and even gas, said Ryan Dunfield, chief executive officer of SAF Group, one of the largest alternative lenders in Canada’s energy sector.

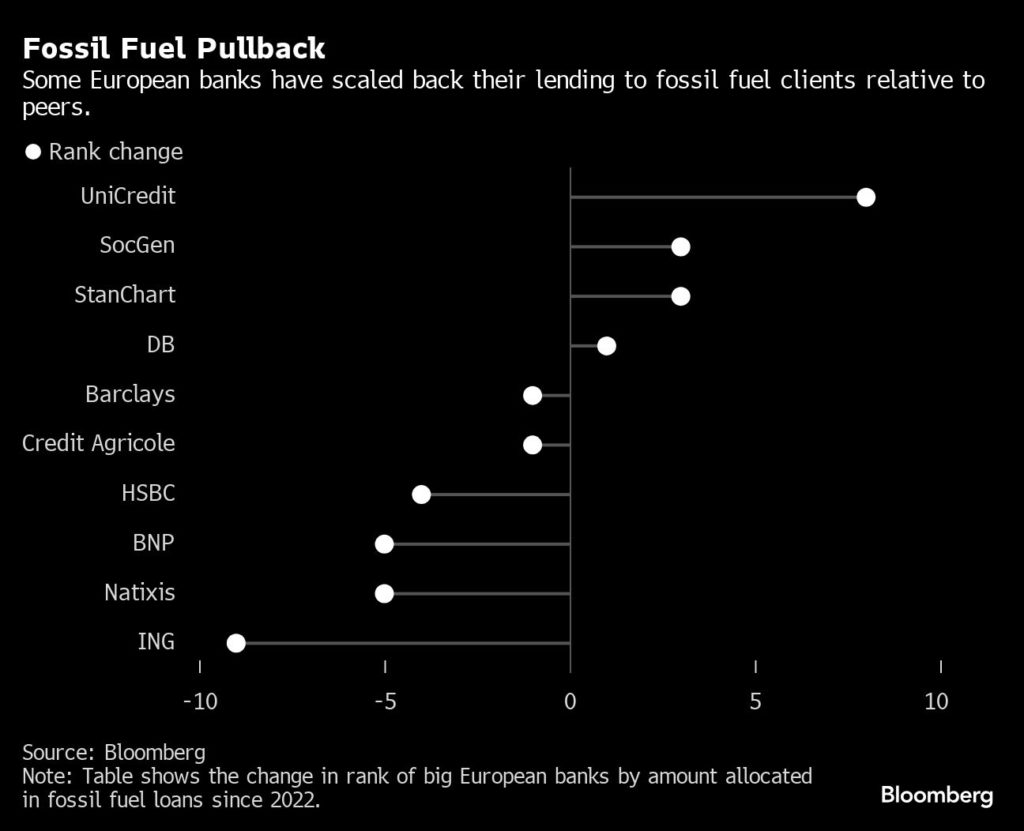

The shift is particularly pronounced among banks based in Europe, where climate regulations are stricter than in other jurisdictions. Lenders stepping up restrictions on fossil-fuel loans include BNP Paribas SA and ING Group NV. The trend is hardest felt by less diversified mid-sized companies with weaker environmental, social and governance policies, according to Dunfield.

European banks that used to be involved in financing oil and gas in SAF’s home market of Canada “have backed out over the past five years,” Dunfield said. Combined with a partial retreat by some US banks, the development has left a financing gap, he said.

Canada is “a very progressive country,” but “a big part of our GDP comes from energy,” Dunfield said. As a result, the “economic engine conflicts with public policy in that sense.”

For companies shifting from banks to private credit, the cost can be considerable. Sydney-based Whitehaven Coal Ltd., whose recent efforts to secure a $1.1 billion loan attracted 17 private credit lenders and just one bank, is paying 650 basis points, or 6.5 percentage points, over the so-called secured overnight financing rate, Bloomberg News reported last week.

The wider development has meaningful implications for everything from credit risk to climate change. From a climate perspective, the riskiest assets are becoming harder to track because their owners aren’t subject to the same disclosure requirements as banks. From a credit perspective, it’s not clear how tougher climate regulations will affect the valuations of high-carbon assets in the years ahead.

Some banks are looking into models that might allow them to shoehorn high-carbon assets into their ESG strategies. HSBC Holdings Plc and Standard Chartered Plc are among lenders currently exploring so-called transition credits. Such financial instruments would be issued by the owners of coal plants to generate the funds needed to cover the cost of closing down operations early.

Other models currently being explored include capital-relief products. Both SAF and Newmarket Capital, a Philadelphia-based alternative asset manager that specializes in structured credit, are pitching so-called emissions-weighted risk transfers to banks. These would see banks packaging and offloading the emissions associated with their loans to third-party investors who aren’t subject to the same climate regulations or scrutiny.

However, such examples of financial engineering have already drawn skepticism from climate activists, who warn they’d do little to actually cut greenhouse gas emissions. Others drew parallels to the kinds of products that are now associated with financial meltdowns.

“Surely the world has learned something” from the global financial crisis of 2008, Simone Utermarck, senior director of sustainable finance at the International Capital Market Association, said in a post on Linkedin.

In the meantime, private credit investors are positioning for more banks to back away from high-carbon clients. A few years ago, SAF launched a C$750 million direct-lending fund for energy companies in Canada. It now has about C$2 billion in capital allocated to the sector, with loan commitments typically ranging from C$20 million to C$250 million for maturities ranging from two to five years.

“We come in and provide incremental capital,” Dunfield said. If banks drop out of group-lending vehicles, SAF can “come in and plug a hole.”

(By Natasha White)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments