Australian thermal coal leaves investors cold

When you’re in the business of buying and selling, timing is everything.

That’s the costly lesson facing BHP Group, which is looking at options to divest its thermal coal assets according to a report Thursday by Thomas Biesheuvel of Bloomberg News that cited people familiar with the matter.

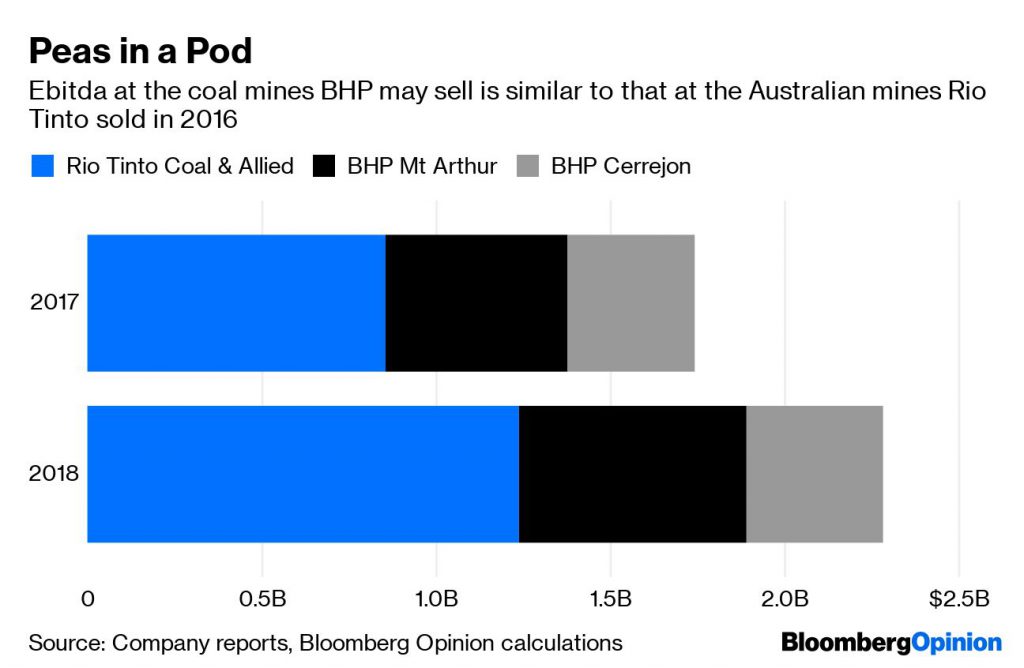

Arch-rival Rio Tinto Group raised $2.7 billion selling mines in the Hunter Valley north of Sydney to Yancoal Australia Ltd., in a process that started in 2016. BHP could get far less: Macquarie Group Ltd. estimates $1.6 billion. That’s despite the fact that BHP’s Mount Arthur and Cerrejon mines, in the Hunter Valley and Colombia, post roughly the same Ebitda as as the ones Rio Tinto sold.

BHP has had good reasons to keep operating these mines. They’ve produced several years of good earnings, for one. Mount Arthur has probably been even more profitable than it looks on paper, thanks to its ability to utilize tax losses that will now be running low.

Still, it will be galling to sell at a discount when the long-term price for the high-energy coal mined in the Hunter Valley is now about a third higher than the $63 a metric ton level at the time Rio Tinto’s deal was announced.

What’s changed? More or less everything.

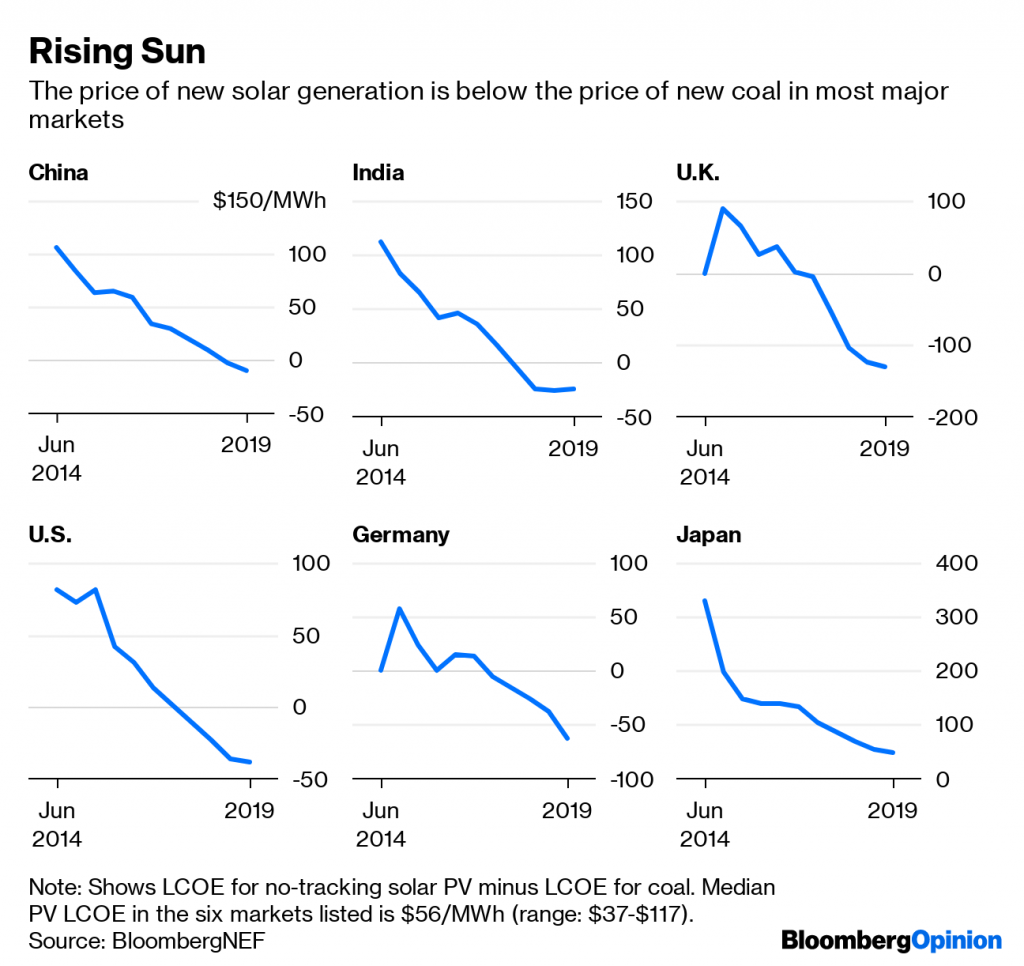

Back in 2016, coal was still the lowest-cost way of delivering new generation in most major markets. The slumping price of wind and solar generation since then has changed the game. Thermal coal will fall to 11% of U.S. generation by 2030 from the mid-20s at present, S&P Global Ratings wrote in a report Wednesday; outside of Spain and Germany, most European coal-fired plants will be retired by 2025.

North Asian markets supplied by Mount Arthur look like an exception, with Japan, South Korea and China making up about 80% of Australia’s thermal coal exports. The first two countries are rare cases where falling renewables costs have failed to undercut the black stuff.

Even there, though, the picture is dimming: Japan’s coal-fired capacity will go into to declinestarting 2023, and actual demand should fall faster since its most recent plants use fuel more efficiently, according to a report this week by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a research group opposed to fossil fuels. South Korea now has taxes on coal amounting to $60 a ton and imports will fall by half by 2040, according to the International Energy Agency.

The group of potential buyers looks thin, too. Anglo American Plc, which has a one-third stake in Cerrejon alongside BHP and Glencore Plc, doesn’t seem in the mood for bulking up. The Japanese trading houses that have historically been major investors in Australia’s mining industry, meanwhile, have been quietly divesting strategic coal stakes for several years.

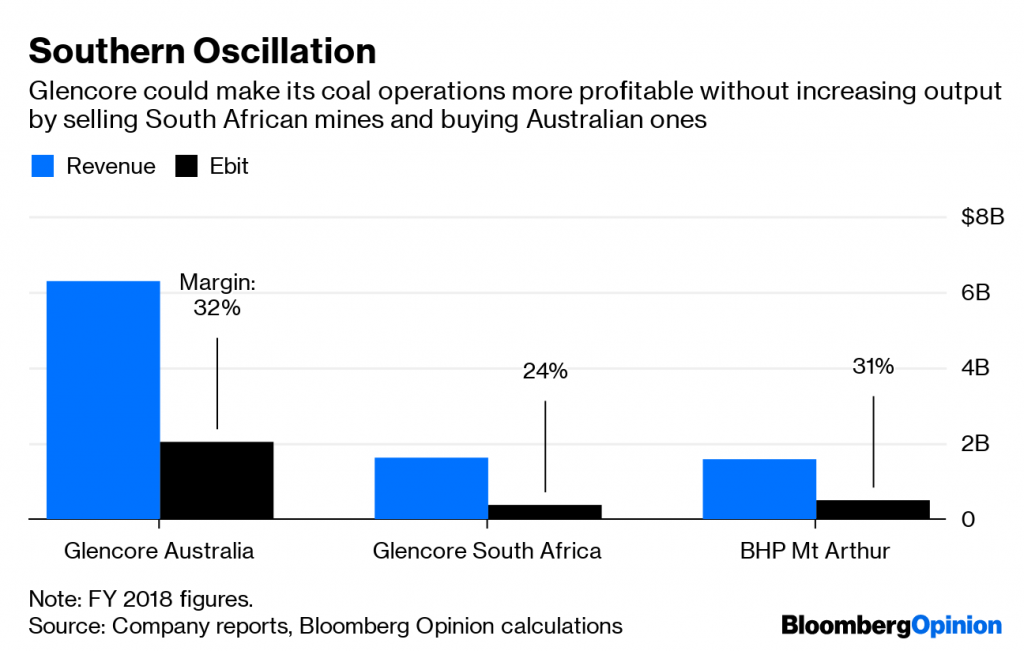

What does that leave? Glencore, despite a promise in February to cap coal output, shouldn’t be ignored. In that announcement, the commodities trader noted it may still buy out some minority stakes, which seems to anticipate a deal on Cerrejon. Glencore could also, in theory, get rid of its South African operations and replace them with Mount Arthur, keeping total output within limits and swapping in a more profitable mine. That would depend on finding a buyer for those South African mines, though, and there’s enough turmoil in that country’s coal and energy sector as it is.

China is another possible buyer for Mount Arthur. The pit is adjacent to Yancoal’s existing operations, suggesting possible synergies. Still, 2019 isn’t the best year to be doing this. Since February, the country has been holding up shipments of Australian coal for ill-defined reasons that have a whiff of geopolitics about them. Any Chinese business looking for government approval to buy an Australian coal mine will have to reckon with that.

Beyond that, there’s even the possibility that smaller local miners will have a go. In the old days, the idea that a relative minnow like Whitehaven Coal Ltd. could absorb a pit the size of Mount Arthur would have seemed absurd, but at Macquarie’s estimate of a $600 million price tag it’s not impossible. Based on BHP’s latest results, a buyer could pay off that sum in 18 months or so and run the mine for cash, assuming rehabilitation costs weren’t too high.

Still, how times have changed. Back when Rio Tinto was hawking its coal assets, the company could plausibly argue that it still saw a bright future for the stuff. Nowadays, BHP is warning that it could be “phased out, potentially sooner than expected,” even as it’s trying to tempt buyers. Those M&A bankers are going to have their work cut out to get a good price.

(By David Fickling)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments