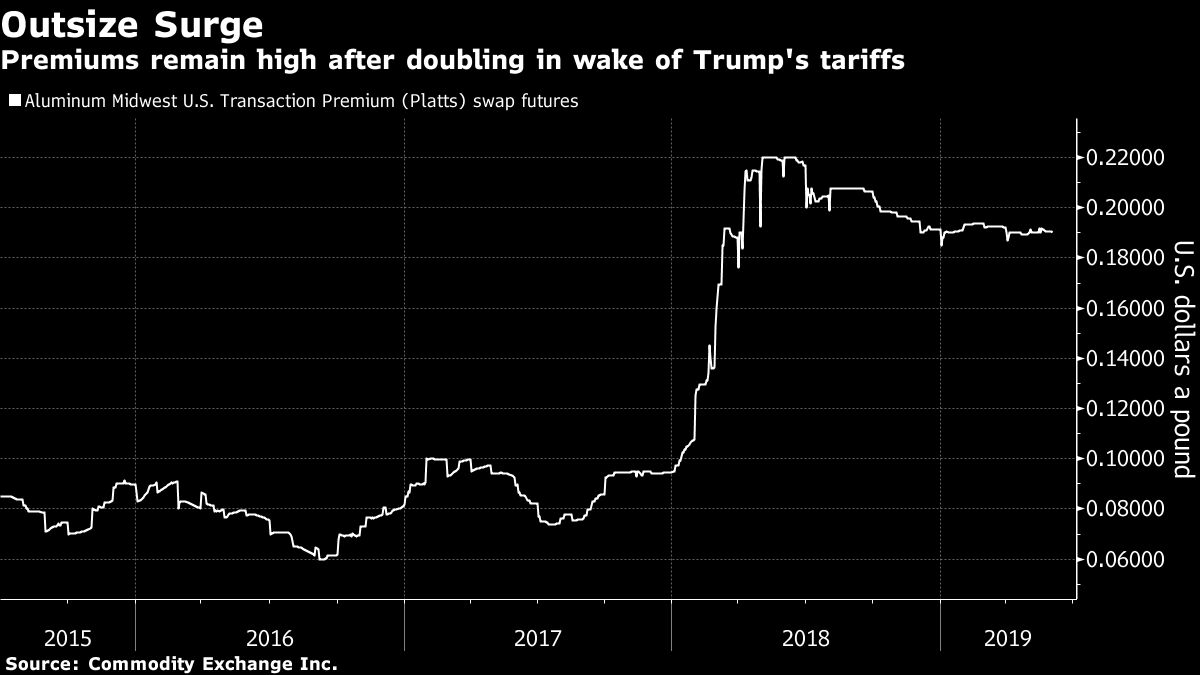

Aluminum’s price premium has doubled and buyers want to know why

Donald Trump’s trade wars are increasing scrutiny of an obscure process that has boosted how much U.S. beer makers and bottlers pay for aluminum cans.

The chairman of Molson Coors Brewing Co. and a bottler for PepsiCo Inc. are urging the U.S. government to investigate the process used to set benchmark aluminum premiums, which have doubled from 2017 levels in the wake of U.S. import tariffs. And the companies may have an ally in Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who says the jump probably isn’t justified.

The premium, which is meant to reflect transportation and handling costs along with the amount of supply available, is determined by London-based S&P Global Platts using its own market surveys. Beverage makers say that the process leaves itself open to manipulation, and want regulatory oversight of how it’s conducted.

Even with an investigation, the authorities are unlikely to find the aluminum premiums are unjustified, said CRU International Ltd. analyst Doug Hilderhoff

“Is it manipulated?” Molson Coors Chairman Pete Coors said in an interview. “It’s a very interesting question. Our thinking is maybe it’s time to have an investigation of that.” The premium increase cost his company’s unit, MillerCoors, $40 million in 2018, he said.

“The data itself has not been challenged and has not been said to be unrepresentative,” Dave Ernsberger, S&P Global Platts’s head of pricing, said in a phone interview. “What MillerCoors appears to be having a problem with is the price of the market, not the data itself.”

As aluminum-market participants gather this week for the biggest North American industry conference in Chicago, the premium surge will be a topic of discussions. The jump is shining a spotlight on an arcane corner of the commodities world, where pricing for several raw materials including metals, oil, coal and iron ore are set by companies such as Platts. That’s unlike stocks and bonds, for which the value is determined by actual trades on exchanges.

Typically, Platts establishes the pricing for various raw materials by surveying market participants including buyers, sellers, traders and brokers. Involvement in the process is voluntary. Those assessments are then often used to determine payments in long-term contracts. The company says it has no vested interest in whether the price of a commodity it covers goes up or down.

The increase in the U.S. Midwest Transaction Premium for aluminum in 2018 reflected a supply squeeze due to America’s import tariffs and sanctions affecting major producer United Co. Rusal, according to Platts’ website.

“The fact of aluminum’s price going up does not seem to justify a huge increase in the Midwest premium,” U.S. Commerce Secretary Ross said in a statement to Bloomberg. “That premium was originally intended to cover transportation handling costs. Those are not a function of the underlying price of aluminum. In addition, the Midwest premium is now based on a survey of market participants, not actual trading.”

Bids and offers

Coors and others complain that participants can cite bids and offers in the market instead of an actual trade, or even worse, they can outright lie about the price. The only way to check is to ask for proof of sale.

“The way that we mitigate against misleading data, anomalous information or even outright lies is by publishing all the information that we collect for everybody in the market to be able to view it, verify it and help us understand if it’s representative of the market,” Platts’s Ernsberger said. “If the data is not right, they need to tell us what isn’t right about it, but we haven’t heard that.”

When beverage makers initially met with Secretary Ross, he was unaware of who sets the premium and how it’s arrived at, said Coors.

CFTC oversight

Meanwhile, his company is urging Congress to consider whether the federal Commodity Futures Trading Commission should have oversight of the pricing process. U.S. Representative Ken Buck of Colorado in February reintroduced legislation to grant the CFTC “exclusive jurisdiction over the setting of reference prices for aluminum premiums.”

In an interview in March, Buck said he’s not alleging there’s price fixing or manipulation, just that he’s asking to give authority for oversight. Kelly Clay, the chief executive of Admiral Beverage — Pepsi’s fifth-largest bottler — says he wants an investigation and questions why there’s no oversight of the Platts process.

Bloomberg LP, the parent of Bloomberg News, competes with Platts and other assessment companies in providing market news and information.

While regulators have probed commodity-pricing processes previously, that hasn’t resulted in major changes. In 2015, the European Commission dropped a probe into the potential manipulation of oil benchmarks, after authorities in 2013 raided the offices of Royal Dutch Shell Plc, BP Plc and others including Platts.

Market deficit

Even with an investigation, the authorities are unlikely to find the aluminum premiums are unjustified, said CRU International Ltd. analyst Doug Hilderhoff. The U.S. still faces a 2-million-ton deficit, even after you account for 2.5 million tons coming from Canada.

That means American users need to import from Russia, the Middle East and other parts of the globe, which get hit with a 10% duty, he said. The Canadians also don’t have any incentive to lower prices.

“You can probably pick holes in people’s pricing methodologies, but in the end that’s how this has been done for decades,” Hilderhoff said.

(By Joe Deaux)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments