A sub-zero wind lights a fire under gold

There’s a standard explanation when gold prices spike, as with their 10% appreciation over the past month: Uncertainty is driving haven demand. People are worried about war in Iran, or a trans-Pacific trade war, or Brexit. In times of crisis, people instinctively cling to bullion.

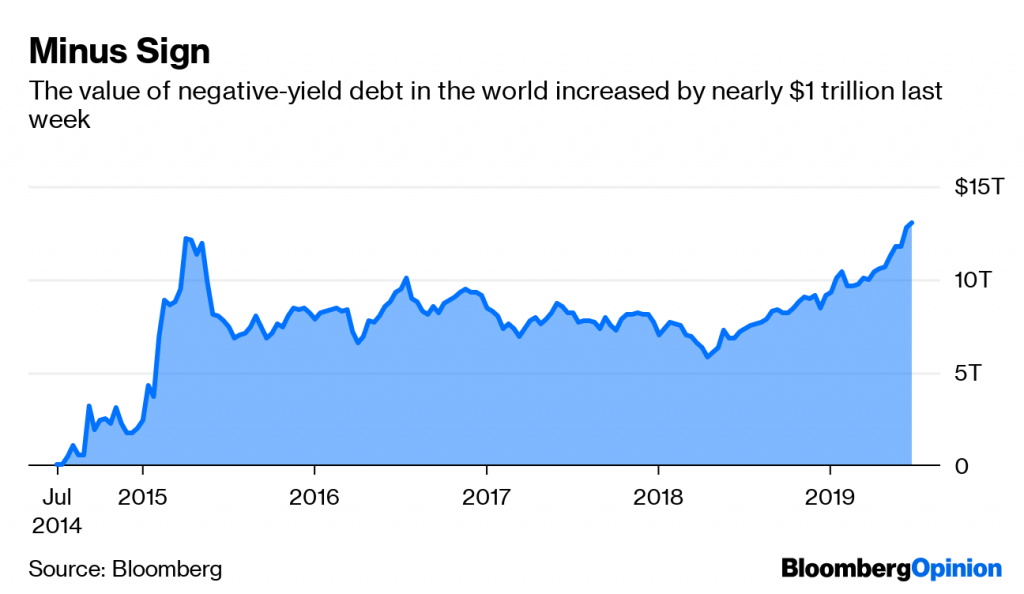

There’s certainly something to that. But an overlooked factor is what’s been happening in the other haven trade, government bonds. The value of debt trading with a negative yield – almost all of it government securities – has increased by more than $2 trillion since late May, and by more than $1 trillion since June 17.

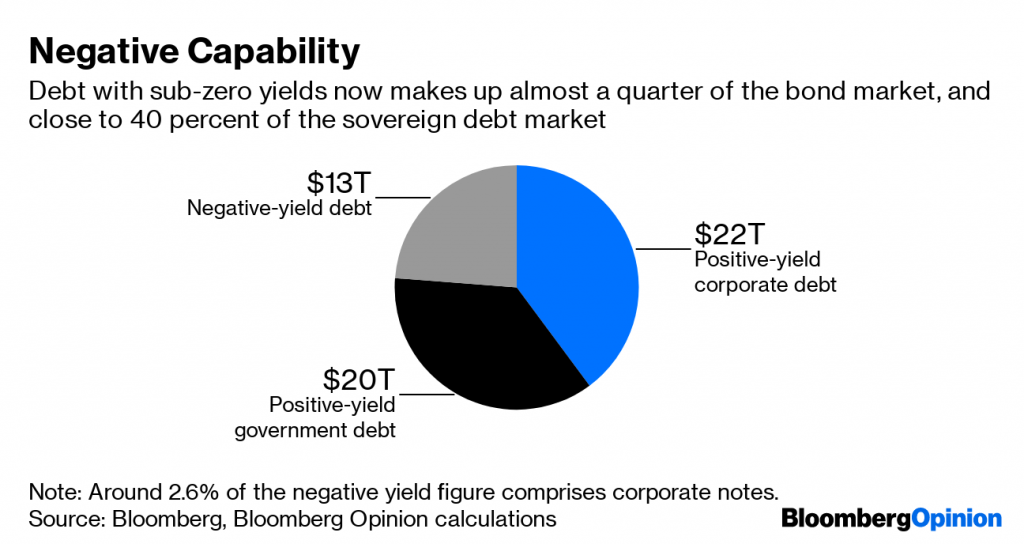

With interest-rate expectations for the weaker European economies getting caught in the slipstream of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s switch toward monetary easing, the negative-yield debt market is now about 22% larger than it was a month ago. Below-zero debt now makes up almost 40% of the value of all government bonds outstanding.

That’s a profound shift. One old nostrum about gold is that it’s fundamentally unattractive because it doesn’t produce any income. Unlike dividend-yielding shares and coupon-paying bonds, you can’t extract cash from commodities unless you sell them – so there’s no insurance against capital losses if they lose value.

The script is reversed when bonds start trading with negative nominal yields. It’s painful to own gold that may fall in value and doesn’t generate any income – but it could be more painful to own bonds that may fall in value while generating negative income.

Paying for the privilege of lending money can make an odd sort of sense given that total returns – yields, plus capital appreciation – are what matter to bond investors. As long as the capital gain is good enough, it doesn’t matter if the yields are underwater. Seen in this light, there’s a more straightforward choice between gold and sovereign debt than the argument about coupons allows.

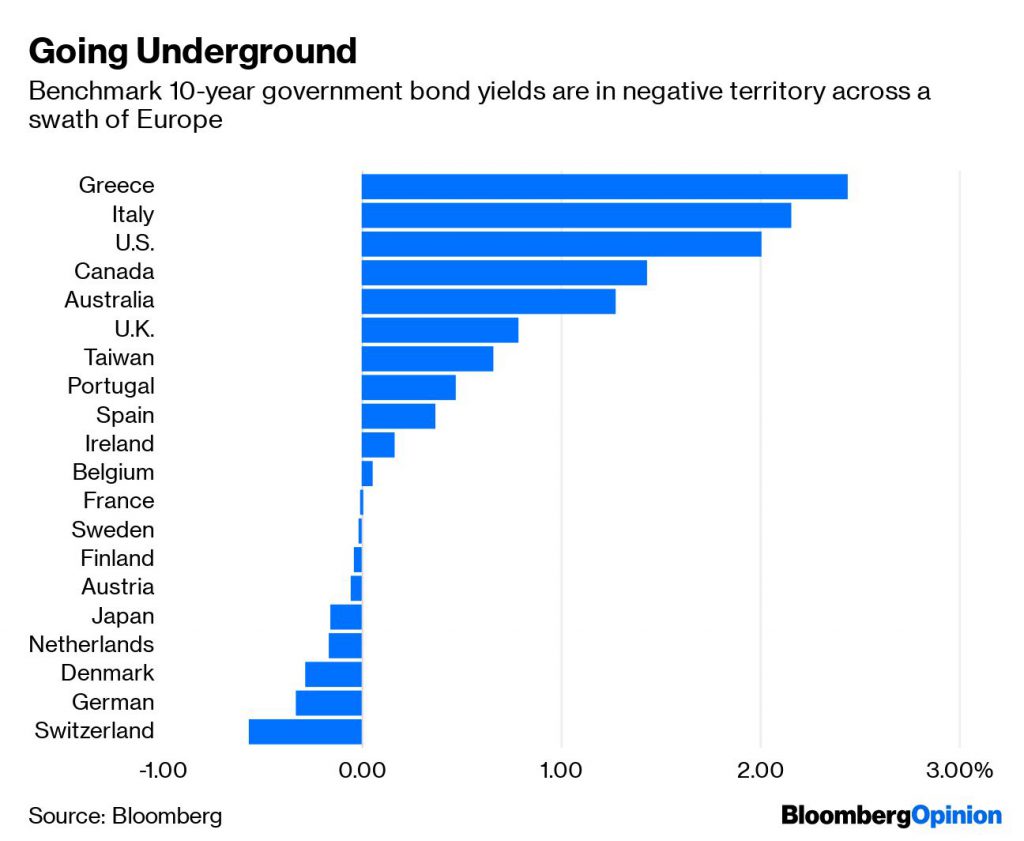

That makes the rising stock of negative-yielding debt a wind at gold’s back, as we’ve argued in the past. Over the past month, benchmark 10-year government bonds in Sweden, the Netherlands, Austria, Finland, and even France have drifted decisively below zero. Those in Germany, Denmark, Switzerland and Japan were already there, and are heading lower.

Some of Europe’s debt-addled economies are flirting with zero, too: The yield on Irish, Spanish, and Portuguese 10-year bonds is below 0.5%, and even Italy can borrow one-year money at a slightly negative yield.

All the private investment gold in the world amounts to no more than about $2 trillion – roughly equivalent to the value added to the negative-yield debt pile over the past month alone. That means only a small shift away from bonds can have an outsize impact on the far smaller gold market – something we appear to have been seeing in recent weeks with the metal’s spike above $1,400 an ounce. (Bitcoin, a more modern barbarous relic with an even smaller market cap of about $227 billion, has gained nearly 60 percent over the same period.)

Bonds still retain a few advantages. If you bought 10-year Swiss government securities – currently the most negative major debt instrument, with a minus-0.565% yield and a price of 105.823 – pretty much the worst that could happen short of an outright default is you lose 10% or so of your investment after holding to maturity.

The downside for gold isn’t unlimited. Most marginal supply comes from mining companies that will suspend operations if they can’t make a profit. It’s hard to see the metal falling below the production costs of the median miner, which tend to be in the $900/oz range. Still, that’s a long way below where we are now, and the gap gets bigger with each gain in the spot price. In practice, though, gold has made only a handful of brief excursions below $1,200 this decade. Treating that as a floor doesn’t seem unreasonable.

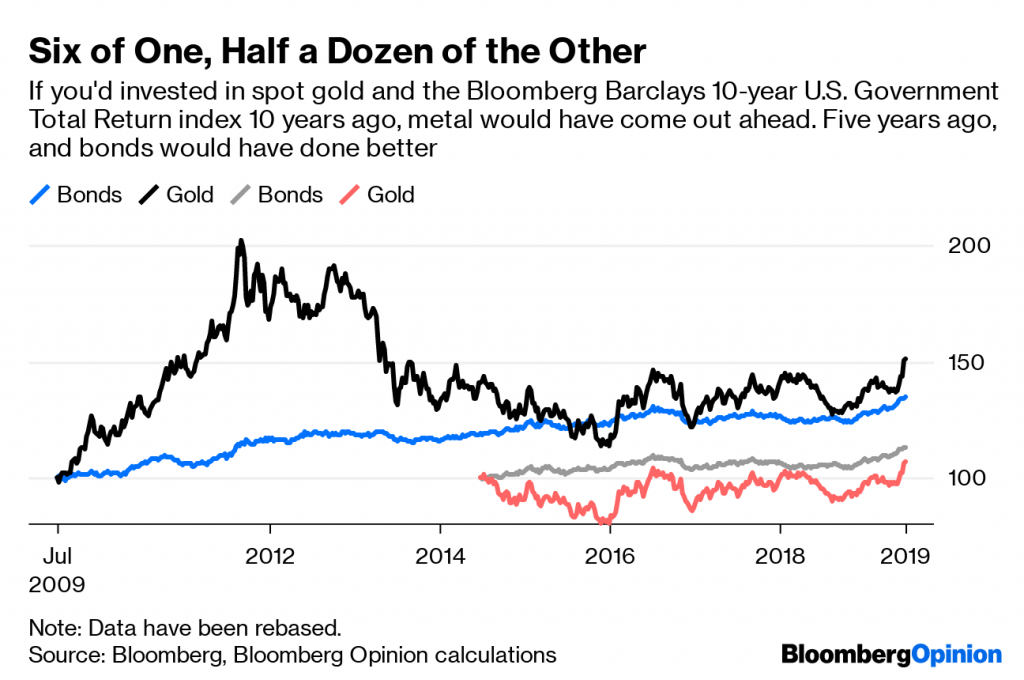

The decision about which asset to own ultimately comes down to whether you think bond total returns or the gold price will perform better. That’s doesn’t present as strong a case for bonds as some might think. Over the past 10 calendar years, the metal has outperformed the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Treasury Total Return index in five. If you’d invested in both five years ago, bonds would have come out ahead; 10 years ago, and you’d have been better off with gold.

That uncertainty is appropriate. If you’re going to make a flight to cash, and things that are cash-adjacent, the decision about what to buy these days is pretty much a coin toss.

(By David Fickling)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments