Taseko and British Columbia First Nation strike truce in epic battle

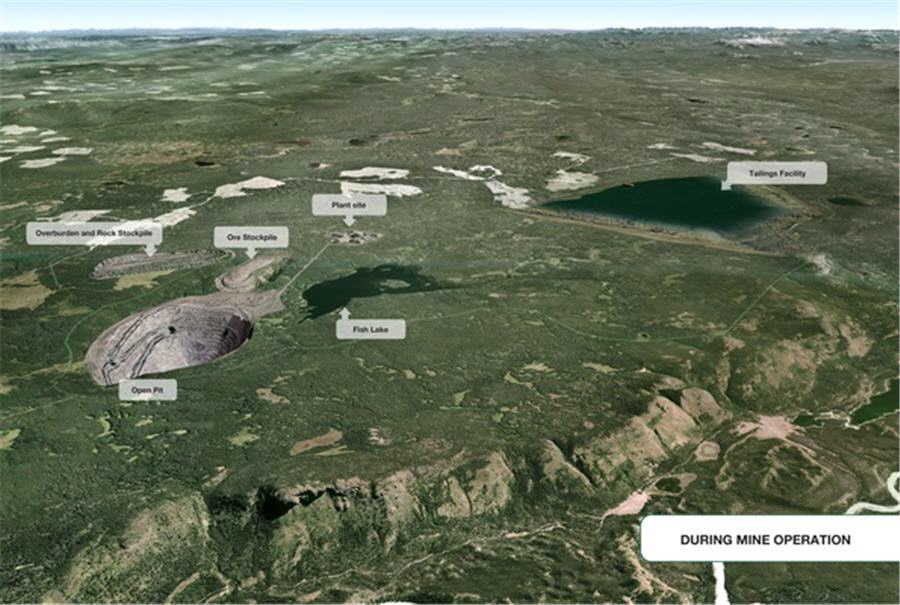

An apparent truce in an epic battle that has gone on for more than a decade between British Columbia’s Tsilhqot’in Nation and Taseko Mines Ltd. (TSX:TKO) over the New Prosperity copper mine has been declared.

The B.C. government announced this week that Taseko and the Tsilhqot’in have agreed to suspend all of its legal and regulatory challenges and work with the provincial government to try to resolve their long-standing differences.

But apart from that, none of the parties are commenting, apart from acknowledging they have agreed to at least talk, which is itself more progress than has been made in more than a decade.

The Tsilhqot’in – which received a landmark Supreme Court of Canada ruling in 2014 that affirmed their title to some of their traditional land – have been intractable on the New Prosperity mine. They have never budged in their opposition to the proposed mine southwest of Williams Lake, which lies just outside the title area recognized by the Supreme Court.

The nation and the company have agreed to pause certain litigation and regulatory matters related to the project while discussions are underway

BC Governemnt

Although the area where the mine would be built lies just outside the area recognized by the court as title lands, the Tsilhqot’in say they also have traditional rights in that area, since they never ceded territory to the colonial government, and in fact went to war in the 1800s to protect it.

“The nation and the company have agreed to pause certain litigation and regulatory matters related to the project while discussions are underway to reach a long-term solution,” the B.C. government says in a press release. “The province has been asked to facilitate this dialogue. The details of this process are confidential.”

Taseko spokesman Brian Battison told Business in Vancouver he could not comment on the development.

As part of the agreement to enter talks, both Taseko and the Tsilhqot’in have asked for a one-year extension to an environmental assessment certificate issued by the provincial government.

“By request of the parties, the BC Environmental Assessment Office has placed Taseko’s application to amend the current environmental assessment certificate in abeyance,” the government states in it news release.

But even if the Taseko and the Tsilhqot’in can somehow reach some kind of agreement, the project still faces a problem at the federal level.

Although the provincial government approved the project with a provincial environment certificate, the federal government’s Environmental Assessment Agency – now the Impact Assessment Agency – refused to issue a certificate not once, but twice, under the Stephen Harper government.

That rejection is still subject to a legal challenge by Taseko.

(This article first appeared in Business in Vancouver.)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments