Scientists working towards superconductors that allow current to flow without energy loss

Physicists at Leipzig University are proposing the idea that in superconducting copper-oxygen bonds, called cuprates, there must be a very specific charge distribution between the copper and the oxygen, even under pressure.

This more profound understanding of the mechanism behind superconductors is expected to bring them one step closer to their goal of developing the foundations for a theory for superconductors that would allow current to flow without resistance and without energy loss.

Back in 2016, lead researcher Jürgen Haase and his team developed an experimental method based on magnetic resonance. The technique allows for measuring changes that are relevant to superconductivity in the structure of materials.

The group was the first in the world to identify a measurable material parameter that predicts the maximum possible transition temperature – a condition required to achieve superconductivity at room temperature. Now they have discovered that cuprates, which under pressure enhance superconductivity, follow the charge distribution predicted in 2016.

“The fact that the transition temperature of cuprates can be enhanced under pressure has puzzled researchers for 30 years. But until now we didn’t know which mechanism was responsible for this,” Haase said in a media statement.

“We established the Leipzig Relation, which says that you have to take electrons away from the oxygen in these materials and give them to the copper in order to increase the transition temperature. You can do this with chemistry, but also with pressure. But hardly anyone would have thought that we could measure all of this with nuclear resonance.”

Closer to the dream

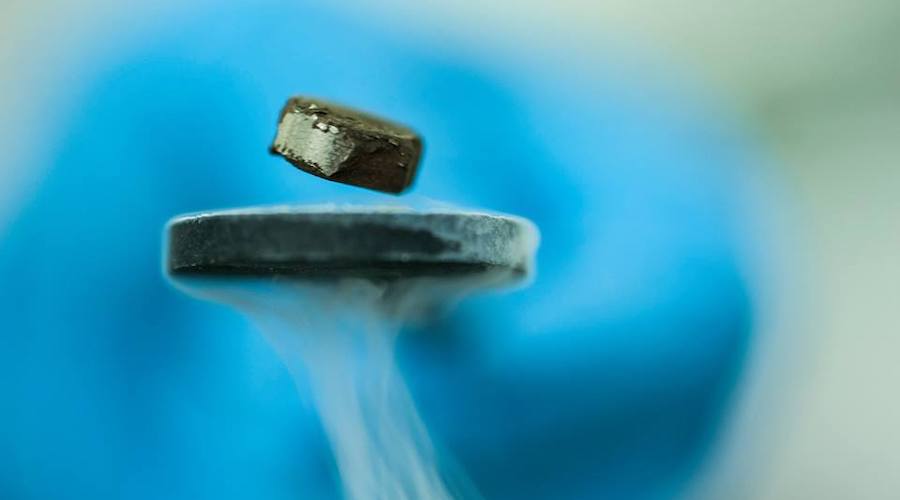

In a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, the scientists explain that their current research finding could be exactly what is needed to produce a superconductor at room temperature, which has been the dream of many physicists for decades and is now expected to take only a few more years. To date, this has only been possible at very low temperatures around minus 150 degrees Celsius and below, which are not easy to find anywhere on earth.

About a year ago, a Canadian research group verified the findings of Haase’s team from 2016 using newly developed, computer-aided calculations and thus substantiated the findings theoretically.

Superconductivity is already used today in a variety of ways, for example, in magnets for MRI machines and in nuclear fusion. But it would be much easier and less expensive if superconductors operated at room temperature.

The phenomenon of superconductivity was discovered in metals as early as 1911, but even Albert Einstein did not attempt to come up with an explanation back then. Nearly half a century passed before BCS theory provided an understanding of superconductivity in metals in 1957.

In 1986, the discovery of superconductivity in ceramic materials (cuprate superconductors) at much higher temperatures by physicists Georg Bednorz and Karl Alexander Müller raised new questions but also raised hopes that superconductivity could be achieved at room temperature.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

BOB HALL

Hopes and dreams. Fusion, superconductors.,and zero loss energy conversion. The rewards would be so great that it is worth working on BUT!!!