Scientists discover “glassy” lithium

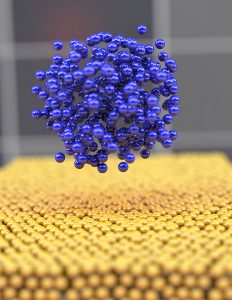

Scientists from the University of California San Diego and the Idaho National Laboratory got a first-time-ever glimpse at the non-crystalline “glassy” lithium that forms at the earliest stages of lithium recharging.

During such stages, slow, low-energy charging causes electrodes to collect atoms in a disorganized way that improves charging behaviour. This had never been observed before.

In a study published in the journal Nature Materials, the researchers say these findings may help fine-tune recharging approaches to boost battery life and for making glassy metals for other applications.

To conduct their experiment, the scholars wondered whether recharging patterns in lithium batteries were influenced by the earliest congregation of the first few atoms, a process known as nucleation.

The foundation that held their question was the fact that in the recharging process of high-energy rechargeable batteries, the way lithium atoms deposit onto the anode can vary from one recharge cycle to the next, leading to erratic recharging and reduced battery life.

To make their observations, the scientists combined images and analyses from a powerful electron microscope with liquid-nitrogen cooling and computer modelling. The cryo-state electron microscopy allowed them to see the creation of lithium metal “embryos,” and the computer simulations helped explain what they saw.

They discovered that certain conditions created a less structured form of lithium that was amorphous (like glass) rather than crystalline (like diamond).

During recharging, glassy lithium embryos were more likely to remain amorphous throughout growth. While studying what conditions favoured glassy nucleation, the team found that they were able to make amorphous metal in very mild conditions at a very slow charging rate.

This outcome was counterintuitive because experts assumed that slow deposition rates would allow the atoms to find their way into an ordered, crystalline lithium. Yet modelling work explained how reaction kinetics drive the glassy formation.

To confirm these findings, the scientists created glassy forms of four more reactive metals that are attractive for battery applications.

According to a university media brief, the results of this study could help meet the goals of the Battery500 consortium, a Department of Energy initiative that funded the research, and that aims to develop commercially viable electric vehicle batteries with a cell level-specific energy of 500 Wh/kg.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments