Russia questions legality of US-planned moon mining pact

Russia is questioning a US-proposed global legal framework for mining on the moon, saying the document would have to be examined thoroughly to make sure it complies with international laws before it is officially proposed.

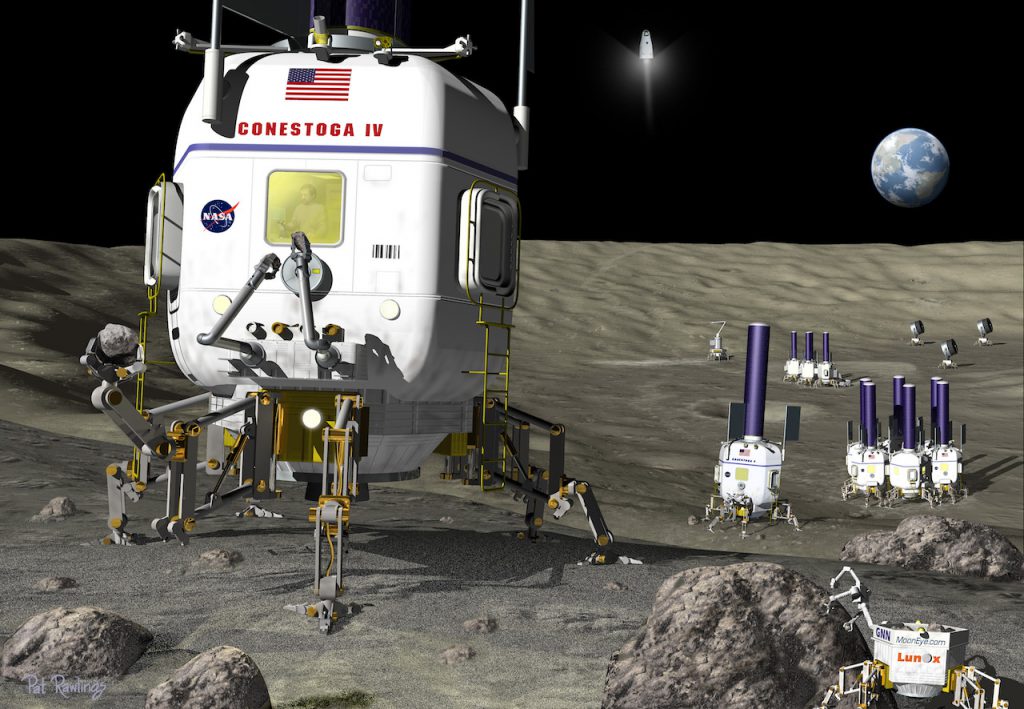

The draft agreement, called the Artemis Accords, would be the latest effort to attract allies to the US National Space Agency’s (NASA) plan to place humans and space stations on the celestial body within the next decade.

The Artemis Accords line-up with several public and private initiatives to extracting resources beyond Earth, but doesn’t include Russia among the early partners

It also lines-up with several public and private initiatives to fulfill the goal of extracting resources from asteroids, the moon and even other planets.

The pact, named after the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s new Artemis moon program, doesn’t include Russia among the early partners, people familiar with the proposed pact told Reuters.

The Artemis Accords are expected to propose “safety zones” that would surround future moon bases. The idea is to prevent damage or interference from rival countries or companies operating in close proximity, Reuters’ sources said.

It also seeks to set a framework under international law for companies to extract and own the resources they mine beyond Earth.

This is not the first times US addresses space mining. In 2015, US Congress passed a bill explicitly allowing companies and citizens to mine, sell and own any space material.

That piece of legislation included a very important clause, stating that it did not grant “sovereignty or sovereign or exclusive rights or jurisdiction over, or the ownership of, any celestial body.”

The section ratified the Outer Space Treaty, signed in 1966 by the US, Russia, and a number of other countries, which states that nations can’t own territory in space.

Long-time coming

President Donald Trump has taken a consistent interest in asserting American power in space. Last year, he formed the Space Force within the US military to conduct space warfare where needed.

In early April, he signed a controversial order encouraging citizens to mine the moon and other celestial bodies with commercial purposes.

The country’s space agency NASA had previously outlined its long-term approach to lunar exploration, which includes setting up a “base camp” on the moon’s south pole.

The Kremlin has been pursuing plans in recent years to return to the moon, potentially travelling further into outer space.

In 2018, it created the Roscosmos State Corporation for Space Activities, a government-controlled entity responsible for a wide range and types of space flights and cosmonautics programs for Russia.

President Vladimir Putin has also vowed to launch a mission to Mars “very soon.”

Trillion-dollar market

The US and Russia aren’t the first nor the only nations to jump on board the lunar mining train.

Luxembourg, one of the first countries to set its eyes on the possibility of mining celestial bodies, created in 2018 a Space Agency (LSA) to boost exploration and commercial utilization of resources from Near Earth Objects.

Unlike NASA, LSA does not carry out research or launches. Its purpose is to accelerate collaborations between economic project leaders of the space sector, investors and other partners.

Thanks to the emerging European network, scientists announced last year plans to begin extracting resources from the moon as early as 2025.

The mission, in charge of the European Space Agency in partnership with ArianeGroup, plans to extract waste-free nuclear energy thought to be worth trillions.

Both China and India have also floated ideas about extracting Helium-3 from the moon’s natural satellite. Beijing has already landed on the moon twice in the 21st century, with more missions to follow.

In Canada, most initiatives have come from the private sector. One of the most touted was Northern Ontario-based Deltion Innovations partnership with Moon Express, the first American private space exploration firm to have been granted government permission to travel beyond Earth’s orbit.

Space ventures in the works include plans to mine asteroids, track space debris, build the first human settlement in Mars, and billionaire Elon Musk’s own plan for an unmanned mission to the red planet.

Geologists, as well as emerging companies such as US-based Planetary Resources, a firm pioneering the space mining industry, believe asteroids are packed with iron ore, nickel and precious metals at much higher concentrations than those found on Earth, making up a market valued in the trillions.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Andrés sorribes

First alien movie ?