New US aluminium import rules bring more transparency, red tape – report

New aluminium metal import rules by the US Commerce Department will likely succeed in fomenting increased supply chain transparency at the cost of more red tape for industry actors, S&P Global’s supply chain intelligence data platform Panjiva warns.

The department published its new rules, set for implementation from June 28, in the Federal Register on May 21. The new system will require import licenses designed to “allow for the effective and timely monitoring of import surges of specific aluminium products and to aid in the prevention of transhipments of aluminium products.”

But Panjiva senior researcher Christopher Rogers interprets the new rules as bringing increased transparency in aluminium supply chains at the cost of increasing their complexity. The new rules come on top of the process of requesting exclusions for individual companies and products.

The new rules bring increased transparency in aluminium supply chains at the cost of increasing their complexity.

To date, around 27,571 requests have been made, according to the Congressional Research Service, of which 61% have been approved.

Rogers expects further complications arising if the Biden administration limits the number of countries subject to duties or quotas.

“Canada and Mexico were already exempted as part of the completion of the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement. The Trump administration also exempted shipments from the United Arab Emirates and Australia from tariffs, while Argentina is subject to a quota. Imports from the EU and UK may also receive exemptions depending on the outcome of current discussions,” the analyst said in a bulletin on May 26.

Higher tariffs

Panjiva data shows US imports of aluminium products covered by the Section 232 duties increased 5.2% year over year in the first quarter, likely reflecting higher prices and the initial downturn linked to the pandemic. Imports were 10.8% lower than in the same period of 2017 before tariffs were introduced.

Section 232 allows tariffs on goods deemed important to US national security.

Rogers noted shipments from Canada and Mexico were now above their pre-pandemic and pre-tariff levels, with growth of 2.2% in the first quarter of 2021 versus the first quarter of 2017.

“Imports from other exempted countries are still lower than before. The outlier has been imports from the EU and UK, which, while 6.1% lower than a year earlier, are above their 2017 levels, which were unusually low at the time,” said Rogers.

Unsurprisingly, imports from countries without an exemption aside from the EU and UK have done worse than average. They dipped 0.7% year over year in the March quarter, masking a 31.5% drop versus 2019 and 26.8% versus 2017.

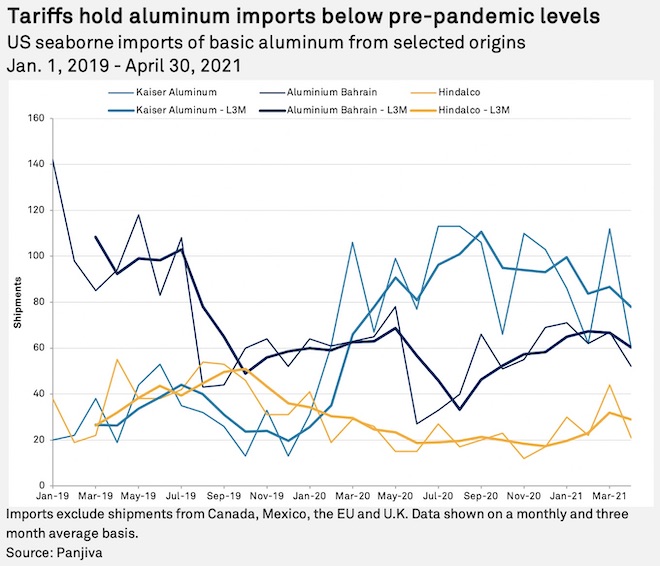

However, US seaborne imports from those non-exempted countries by most of the major importers are still in a state of declining shipments. For example, shipments linked to Aluminium Bahrain BSC were down 20% year over year and were 44.6% lower than in 2019.

Shipments associated with Kaiser Aluminum Corp. were down 10.4% year over year but improved versus 2019. Hindalco Industries, meanwhile, began to decline in April with a 19.2% drop, which may worsen depending on the impact of the rapidly spreading pandemic in India.

Last year, the US Trade Representative made an about-turn on reimposing tariffs on Canada-produced aluminium products mere hours before Canada introduced dollar-for-dollar countermeasures to the tune of $2.7 billion (C$3.6 billion) on US-made aluminium products.

Reducing overcapacity

Meanwhile, the US-based Aluminium Association on May 17 welcomed a joint commitment by the US and the EU to address overcapacity in the global aluminium market.

“This is an extremely important step toward a better trading relationship with a vital ally while addressing systemic aluminium overcapacity,” said CEO Tom Dobbs in a press release.

Section 232 tariffs had done little to change Chinese industrial practices.

The association argues that massive state subsidies for aluminium production – especially in China – have distorted markets and made it difficult for many aluminium producers to compete on a level playing field for too long.

“It is time for nations committed to a market and rules-based global trading system to come together to combat this shared challenge. Any final agreement with Europe should emphasise strong trade enforcement based on a common set of rules,” said Dobbs.

A recent report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development found that three years of Section 232 tariffs had done little to change Chinese industrial practices.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments