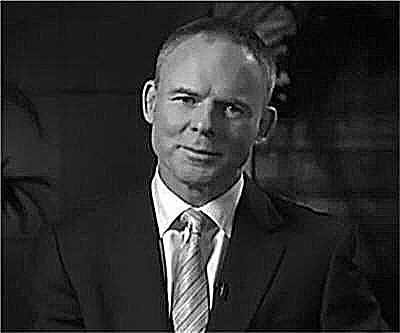

Mean reversion: Kloppers says iron ore is back to being a volume game, get used to it

Iron ore pulled back slightly on Friday to trade just under $120 a tonne – a psychologically important level for the industry – after gaining 37% since hitting a three-and-a-half year low of $86.70 in September.

For the big three exporters – Vale, BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto – $120 provides a very comfortable margin, given cost of production for these giants of between $40 – $50 a tonne.

But it’s a far cry from the heady days of early 2011, when iron ore peaked at just under $190 a tonne as demand from China spiked and supply of ore (and met coal) could not keep up.

Platts quotes BHP Billiton CEO Marius Kloppers during the company’s annual general meeting yesterday as saying these kind of prices will not be repeated and that the industry is experiencing “mean reversion”:

“We are now witnessing a rebalancing of demand and low-cost supply, and a progressive recalibration of prices towards more sustainable levels. This industry’s ability to meet incremental demand with low-cost supply has improved and, in this regard, the opportunities that lie ahead will be volumetric as opposed to price-based.”

If iron ore is back to a strictly volume game it’s not great news for the many projects outside Australia’s Pilbara and the choice deposits in Brazil that Vale has been exploiting so successfully.

Apart from the advantage of already-developed infrastructure, the ore in these regions is of such a quality that many mines there look more like quarry operations than ore processing facilities.

By comparison projects like those in Canada’s Labrador Trough and the new iron districts in West Africa require much more upfront investment and are much higher cost operations.

As for the highly-fragmented domestic Chinese industry which mines more than 1.2 billion tonnes of low-grade ore a year; they’ve long been forced to feed on scraps.

A new report shows that the top steel mills in China now import almost 90% of their requirements.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments