Laser mining – the light at the end of the tunnel?

At the very heart of mining lies the tough task of breaking up rocks. In the heart of US mining country, Coeur D’Alene, Idaho, a team of engineers is building a machine that they believe can take it on – with lasers.

Merger Mines Corporation (OTC: MERG) said it is doing what nobody in the industry is doing – and has applied academic conceptualization, computer modeling, and study of laser technology to engineer and design its inaugural “thermal fracturing” prototype units.

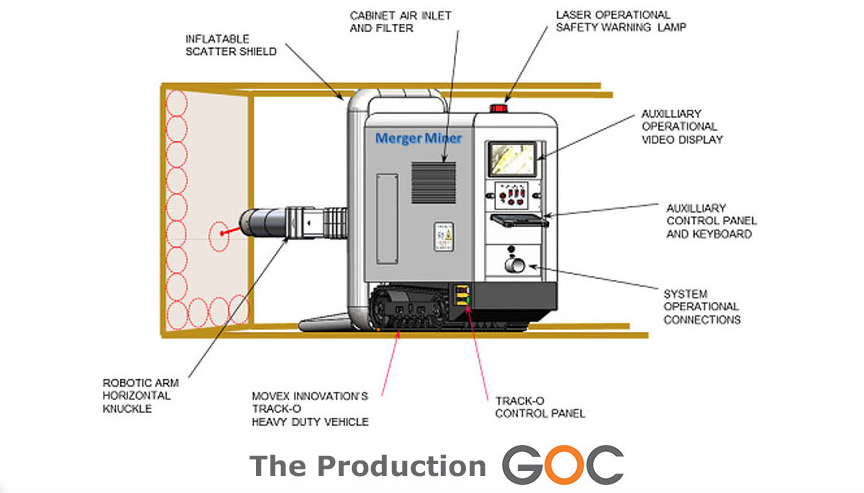

The application of the “Graduated Optical Colimator” (GOC) for the mining industry consists of a one-kilowatt optical power fiber laser to selectively spall igneous geological formations containing narrow veins of precious metals.

Merger said the prototype addresses key issues like mining using less explosives, chemicals and waste.

“We’ve been working at this problem for five or six years now – and we’ve discovered that a lot of laboratory research has been done in the private sector and in the government sector,” Gary Mladjan, Merger Mines’ VP, engineering and technology told MINING.COM.

“Argonne National Labs in Chicago did the first demonstrations to prove their fracturing methods for breaking up rocks, but they were working mostly in the oil and gas industry.”

Mladjan said the GOC is only three feet high and six feet wide – small enough to be helicoptered into a mine site.

Mladjan, who has served in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, said past tests on mine sites using lasers have used too much power and have wound up melting or vaporizing rocks, as every rock specimen will have different needs for power.

“Where the fracturing is – it’s a very narrow margin [that] depends on laser power, which is low level, and the duration of the exposure to the rock where you actually get the thermal fracturing,” Mladjan said. “Argonne did this in sandstone and shale, another study in Europe did it in graphite, which is more akin to what we’re doing.”

Mladjan said the lab experiments calculated the impact of the fracturing, and when Merger reviewed the papers, they realized Argonne proved what can be done, so Merger productized the findings of abundant research.

“The reason we are able to do that is based on the research of a number of people who are advisers for us and their experience in industry,” Mladjan said.

“If you look at lasers in mining, what you’re finding is it is being used to measure distances, and not doing any actual mining”

Gary Mladjan, Merger Mines VP, engineering and technology

“We’ve come up with a method where we can do that exposure duration that will thermally fracture the rock. If you look at lasers in mining, what you’re finding is it is being used to measure distances, and not doing any actual mining.”

Currently, the machine is a test instrument with the concept model built, and the production unit would be autonomous.

“What we developed this for was to go back in and work some of the older mines that have been shut down or abandoned that has narrow veins that are not economically feasible to work with today’s conventional mining,” Mladjan said.

“We can go into some of these older mines that were done in the 1890s or 1920s or 30s where that was how they did it – blasting was like a one-man operation.”

Merger has been looking at mines like Lucky Friday in Silver Valley where there are a number of stringers off to the side that could be valuable, but not for a large operation.

“We can go in and follow a very narrow vein to wherever it takes us.”

Mladjan said the GOC can differentiate between host rock and waste rock and direct the waste material away and harvest the ore- bearing material, and it doesn’t use a crusher, which produces tailings.

The GOC, Mladjan said, can go back to existing mines that miners gave up on because couldn’t identify ore using existing mining methods and extend the life of the mine by going after [what] they left behind.

“This could be cost-cutting,” Mladjan said. “You [could] afford to go back in and turn marginal mines into profitable mines.”

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments