How Ivanhoe’s giant new Congo mine stacks up against copper mining’s top tier

When Ivanhoe Mines’ Kamoa-Kakula project in the Democratic Republic of Congo went into production a month ago it was the biggest new mine to do so since Escondida in Chile in November 1990.

Escondida hit its stride eight years later, producing 867,000 tonnes on its way to a peak of more than 1.4m tonnes a decade later. With more than 50 years left, the BHP-Rio Tinto owned operation may remain unsurpassed over its life in terms of sheer size.

A new report by BMO Capital Markets analyst Andrew Mikitchook outlines a similarly rapid growth path for Kamoa-Kakula, with the DRC mine entering peak production of 841,000 tonnes by 2028.

Kamoa-Kakula may never hit seven figures in annual output (although exploration on Ivanhoe’s adjacent Western Foreland licences which the Vancouver-based company owns 90%–100% of may transform the complex’s prospects once again) but size is not necessarily its standout feature.

Grade is.

According to a 2019 PEA, Kamoa-Kakula is being developed in 5 phases of 3.8m tonnes (phase 2 has been brought forward to Q3 2022) for total ore processing capacity of 19m tonnes per year.

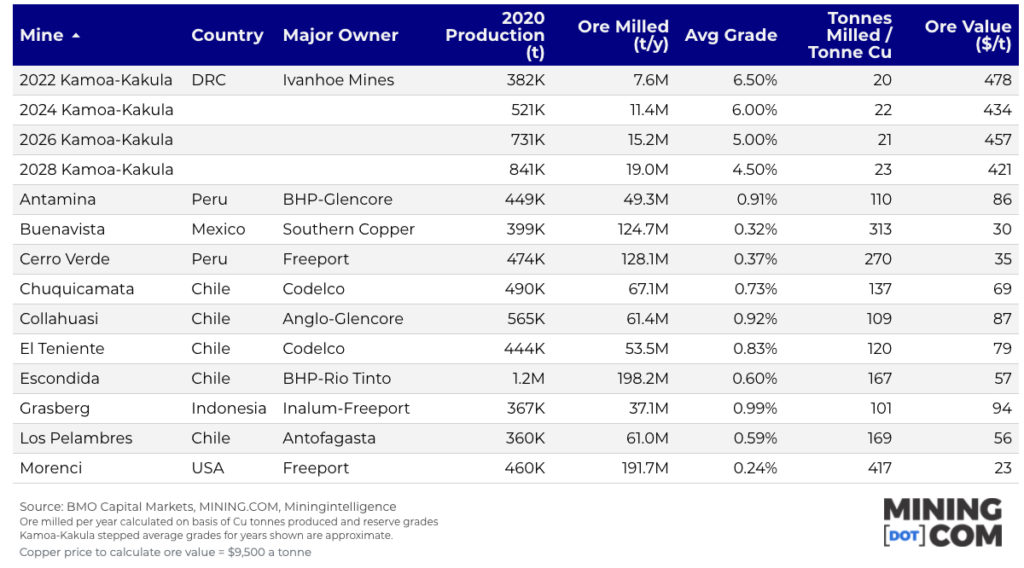

The first table based on BMO’s ramp-up projections compares Kamoa-Kakula with the 10 largest copper mines in the world based on 2020 production volume. At the bumper grades during ramp-up, Kamao-Kakula’s ore is many factors more valuable than its peers.

Next year the mine will enter the top 10, and by 2026 when it enters steady state production it will vie with Freeport’s Grasberg, itself in aggressive ramp up, as the number two mine in the world.

That year – all things being equal and of course they won’t be – every tonne milled would be worth eight times Escondida’s, 20 times Morenci’s and even against Grasberg’s underground expansion, it’s a factor of five (solely on a Cu basis – Grasberg’s gold and silver credits put it in a different camp altogether).

Grade at Kamoa-Kakula declines steadily over the five phases as per the PEA, averaging between 4%-3% during the second half of its 47-year mine life, but even then Kamao-Kakula would be by far the richest copper mine almost of any size on the planet.

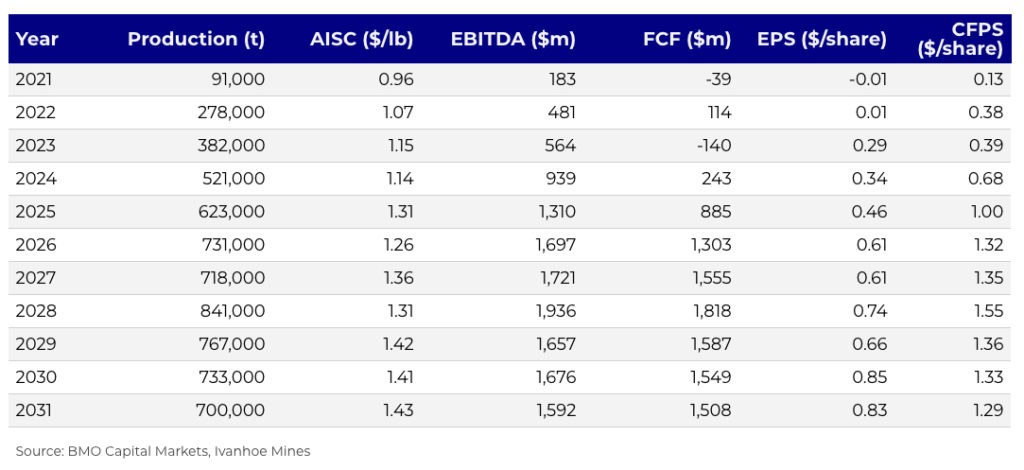

Table 2 shows BMO’s projected performance metrics for the mine and Ivanhoe’s financial performance, showing how Kamoa-Kakula’s ore quality feeds into low all-in sustaining costs (comparable with the 2020 PEA) and torrents of free cash – topping a billion just four years after first concentrate.

The performance stats show Kamao-Kakula production at 100% (for consistency with company disclosure) and adjusted for the actual startup on 25 May. The financial metrics include Ivanhoe’s revival of the Kipushi zinc-copper mine from 2024 and the Platreef project (PGM-Ni-Cu-Au at 4mtpa) in South Africa from 2026.

Even at 39.6% ownership (matching that of Zijin Mining with Kinshasa holding a fifth) BMO points out that Ivanhoe’s stake is still substantial at just below 300,000 tonnes for most of the mine life. And the potential cash flow streams attributable to Ivanhoe is an indication of its ability to self-finance through phase 5 as well as Kipushi and Platreef, says Mikitchook.

BMO has an outperform rating on Ivanhoe Mines (TSE:IVN) and upped its price target to $15.00 in this report. Ivanhoe was last trading at $8.54 a share in Toronto with a market value of C$10.3 billion ($8.4 billion). Copper was last trading at $4.32 a pound or $9,525 per tonne.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments