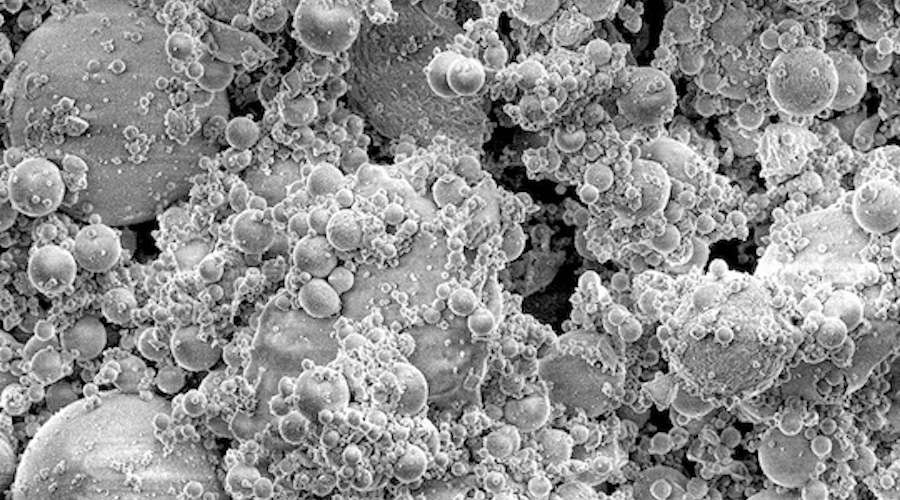

High-quality concrete produced with coal fly ash

Researchers at Rice University are employing flash Joule heating to remove toxic heavy metals from fly ash, a powdery byproduct of coal-based electric power plants that is used frequently in concrete mixtures.

In a paper published in the journal Communications Engineering, the scientists explain that using purified coal fly ash reduces the amount of cement needed to produce concrete and improves the quality of the latter.

According to the experts, the production of cement accounts for roughly 8% of the world’s annual carbon dioxide emissions. To address this issue, chemist James Tour experimented with replacing 30% of the cement used to make a batch of concrete with purified coal fly ash. The process improved the concrete’s strength and elasticity by 51% and 28%, respectively, while reducing greenhouse gas and heavy metal emissions by 30% and 41%, respectively.

“You can use less concrete if you use coal fly ash. However, fly ash contains heavy metals,” Tour said. “Often, we try to fix one thing and we mess something else up. In our effort to do something with this waste, namely coal fly ash, we were polluting our environment because the heavy metals were leaching out. Water carried it into our environment and contaminated our soil along roadways, etc.”

The researcher pointed out that roughly 750 million tons of coal fly ash are produced worldwide each year. The new flash Joule heating-based process, however, can remove up to 90% of the heavy metals in it using zero water and making it fitter for infrastructure use.

“Basically, we mix the fly ash with carbon black, because fly ash does not conduct electricity, and the carbon black makes the mixture conductive,” Bing Deng, lead author of the study, said. “Next, we place the mixture between two graphite or copper electrodes and use a capacitor to supply a short current pulse to the sample. This current input brings the sample temperature up to about 3,000 degrees Celsius. The high temperature makes the heavy metals evaporate into a volatile stream which is then captured.”

Deng noted that by using this method, it is possible to eliminate the heavy metals from coal fly ash with high efficiency. For different heavy metals like arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, nickel and lead, the removal efficiency registered was up to 70% to 90% in just one second.

Flash Joule heating was also shown to work on different coal fly ash compositions resulting from the combustion of coal extracted from various geographical locations.

“There are two main classes of fly ash with different inorganic compositions, Class C and Class F,” Deng said. “We found that our method works for both kinds of coal fly ash. It also works for other hazardous wastes like red mud or bauxite residue. This shows that the process can become a generalized approach for large-scale industrial solid waste decontamination.”

Civil engineers happy

Following the positive results in the chemistry lab, the new concrete was tested by civil engineers. They found that by replacing 30% of the cement in a concrete mixture with the purified coal fly ash, the compressive strength and the elastic modulus of the composite increased significantly.

“This is very meaningful for structural engineering and the construction industry because stronger structures can be built with less cement,” Wei Meng, co-lead author of the study, said “That is why this research is valuable to civil engineers.”

The Tour lab’s process also allows for the evaporated heavy metals to be collected in a vacuum chamber rather than released into the environment. Moreover, the energy consumed during the process is relatively low.

“We calculated that energy consumption is about 532 kilowatts per ton,” Meng said. “If we convert this to Texas electricity prices it comes out at about $21 per ton. The life cycle analysis shows we can actually extract value from these waste materials.”

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments