CHARTS: Copper price bulls bring back $10,000 forecasts

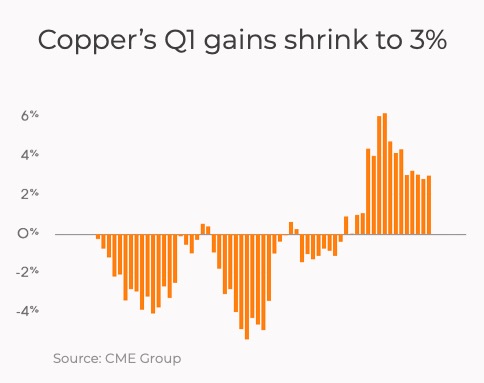

After a solid lift to near one-year highs, the copper price is once again in danger of falling below the pivotal $4.00 a pound ($8,820 a tonne) level, closing the first quarter at $4.0115 a pound in New York. LME prices have followed the same course after hitting a high of $9,164.50 on March 18.

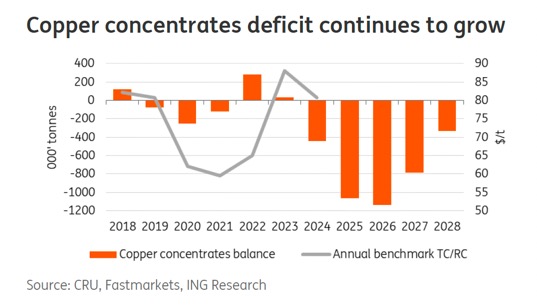

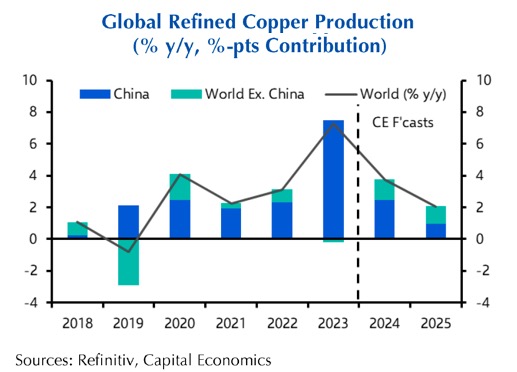

Copper’s runup was sparked by pledges from Chinese smelters to cut output by 5%-10% in the face of tighter-than-expected concentrate supply and overcapacity after years of relentless expansion which has lifted the country’s global refining share to over 50%.

Concentrating minds

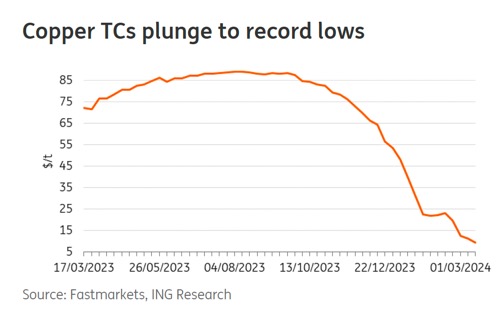

Evidence of how desperate Chinese refiners are to source raw material is a report out Thursday by Bloomberg that BHP sold concentrate from Escondida, the world’s largest copper mine, at spot treatment charges as low as $3 per tonne and refining charges of 0.3 cents a pound to at least one Chinese smelter.

That constitutes at least a decade low – when prices declined to below $8,000 a tonne in 2023, treatment and refining charges – paid by miners to refiners to convert concentrate into metal – were north of $90 a tonne. Benchmark annual contracts remain much higher but fell for the first time since 2021.

China would also increasingly compete with India for raw material in 2024 – just this week Adani said it started operating the first unit of its $1.2 billion Kutch Copper smelter. The plant will be the world’s largest single-location copper smelter with an initial capacity of 500kt a year and double that in the second phase of the project.

Uncertainty remains about the impact of decisions by the so-called Copper Smelters Purchasing Team (CSPT) at its quarterly meeting in Shanghai currently under way. In the initial announcement, the group of 19 smelters stopped short of agreeing to outright coordinated cuts but vowed to rearrange maintenance, limit runs and delay the startup of new projects.

Indeed, China’s top producer Jiangxi Copper said in its earnings report this week that while it wants to maintain capacity discipline it nevertheless plans to raise copper production this year by 11% to 2.32m tonnes.

A copper ore export ban in Indonesia coming into effect in June could turn out to be the tipping point for the CSPT.

ING investment bank in a note also points to signs of still muted demand in China evidenced by inventories on the Shanghai Futures Exchange which have recently hit their highest level since 2020 and are approaching 300kt.

At the same time, as detailed by Andy Home of Reuters, market open interest on the ShFE has jumped to life-of-contract highs and managed money investors on the LME and CME exchanges have sharply increased long positions.

Fears over undersupply

While plummeting TC/RCs have concentrated minds on copper supply, lack of growth and disruptions at mine levels have been plaguing the industry for years, as have worries about depletion and falling grades at the world’s top copper mines (the top 20 mines have weighted discovery year of 1928).

The biggest bombshell to hit the copper market in decades was the closure last year of First Quantum’s Cobre Panama mine after massive protests in the central American nation. At 350kt of copper in concentrate, the $10 billion Cobre Panama mine accounted for around 1.5% of global copper output.

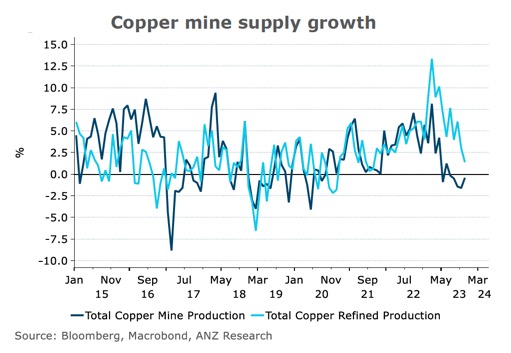

The Panama fiasco stands out, but unplanned disruptions are a feature not a bug of the global copper industry. Antipodean investment bank ANZ points out at the beginning of 2023, mine production for 2024 was forecast to grow by over 6% year on year but after only one month this growth forecast decreased to 3.9%.

Anglo American’s move to slash production blaming low grades and high costs led the London-listed company to cut its target for 2024 from 1m tonnes to between 730kt–790kt. ING says output at Escondida, the only copper mine producing more than 1m tonnes per year, is expected to be at least 5% lower in 2025 than it is today.

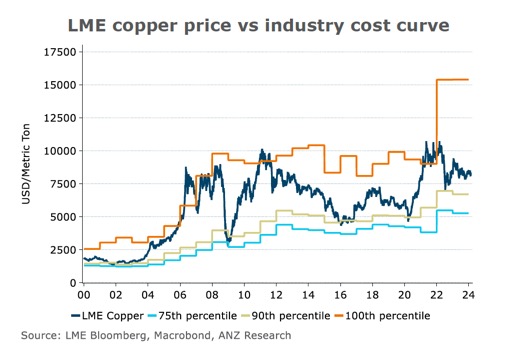

ANZ says the average total cash cost of producing a tonne of copper has risen more than 30% to $5,600 over the past three years and while inflation is subsiding elsewhere in the economy, miners continue to face increasing labour and energy costs.

ANZ raised its supply disruption factor to an above average rate of 6% in 2024. That would be the equivalent of the loss of both the United Arab Emirates and Nigeria’s oil output for the year on crude markets.

Meanwhile production at Codelco, the world’s top producer of the red metal, is sitting at 25-year lows and the state-owned firm has admitted that promises of a recovery (which have been made many times in the past) should it pan out this time would be slow.

Five digit copper

Just how quickly conditions can change is clear from the prediction by the Lisbon-based Copper Study Group (ICSG), which as of late October last year was predicting the biggest surplus in a decade on copper markets of nearly half a million tonnes.

Given developments since then, copper watchers have been forecasting deeper deficits or flipping expected surpluses and upping forecasts for the copper price.

ANZ sees copper topping $9,000 in the short term and trading above $10,000 over the next 12 months as refined deficits reach 400kt. ING sees copper at $9,000 by the end of the year and concentrate deficits above 1m tonnes in 2025 and 2026.

This week BMO Capital Markets, not always in the copper bull camp, increased its previous forecast for the long term price of copper to over $9,000.

Perennial copper bulls Goldman Sachs sees the metal trading at $10,000 a tonne by the end of the year while Capital Economics now sees a $9,250 price by the end of 2024.

As for the long term demand outlook, few analysts have graphs that don’t start in the bottom left corner and end near the upper right.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments