Activists, Hollywood take down top 50 mining company

The ranks of the most valuable mining companies in the world were throughly scrambled in 2023 as governments intervened, lithium and nickel prices tumbled, gold hit records and a new listing went ballistic.

At the end of 2023, the MINING.COM TOP 50* ranking of the world’s most valuable miners reached a combined $1.42 trillion, up a healthy, if far from spectacular $48.7 billion over the course of 2023. Mining’s top tier is also worth $330 billion less than in March 2022.

Metal and mineral markets are volatile at the best of times – the nickel, cobalt and lithium price collapse in 2023 was extreme but not entirely unprecedented. Rare earth producers, platinum group metal watchers, iron ore followers, and gold and silver bugs for that matter, have been through worse.

Mining companies have become better at navigating choppy waters and as a whole the majors performed fairly consistently last year despite geopolitical and market turmoil, but within the ranking, 2023 fortunes were made and lost over what seemed like days.

The forced closure of one of the world’s biggest copper mines – and the subsequent collapse of owner First Quantum Minerals stock – served as a stark reminder of the outsized risks miners face over and above market swings.

Panama root canal

After months of protests and political pressure, at the end of November the Panama government ordered the closure of First Quantum Minerals’ Cobre Panama mine following a ruling by the Supreme Court that declared the mining contract for the operation unconstitutional.

Public figures, including climate activist Greta Thunberg and Hollywood actor Leonardo Di Caprio backed the protests and shared a video calling for the “mega mine” to cease operations, which quickly went viral.

That mining cobre is at the nexus of the green energy transition is clearly an irony lost on those trying to save the world. FQM is seeking arbitration and completely winding down operations will take time, but a reopening of Cobre Panama is not on the cards.

From 25th position in the ranking at the end of March 2022 and a valuation well above $20 billion, the November-December sell off saw FQM drop out of the top tier altogether, ending 2023 at number 58 with a market cap below $6 billion.

Cobre Panama supplied more than 40% of the company’s revenue, and with nickel prices plummeting FQM has also been forced to suspend operations at its Raventhorpe mine in Australia.

Amid the inevitable takeover rumours now in circulation, shares in the Vancouver-based company have rallied in 2024, but still not enough to reenter the top 50.

No. 12 with a bullet

If 2023 was an annus horribilis for FQM it was mirabilis for Amman Mineral Internasional. Stock in the Indonesian firm surged by 269% from its July debut in Jakarta to reach a market capitalisation of more than $30 billion at the end of last year – and number 12 in the ranking.

That valuation is quite an achievement on annual revenue of $2 billion no matter how fat margins are at the company’s Batu Hijau copper and gold mine. Batu Hijau is the third largest mine worldwide in terms of copper equivalent output (but no match for Cobre Panama when it comes to the orange metal alone) and has been in production since the turn of the millennium. Amman is also developing the adjacent Elang project on the island of Sumbawa.

Amman Minerals’ ascent has minted at least six new billionaires and the stock appears to be building on its success in 2024, rising by double digits in January already.

Indonesia’s other major mining IPO, Harita Nickel, was on a different trajectory altogether. After listing in April and raising $672m, the company has had a tough go of it and the stock has shed more than 38% since then as nickel prices continue to decline.

Shiny gold, dull silver, tarnished PGMs

The price of gold hit an all-time record on December 1, 2023. But bullion’s best ever level passed without the usual fanfare and despite bullish indications for 2024, gold mining stocks did not exactly storm the rankings of the most valuable miners.

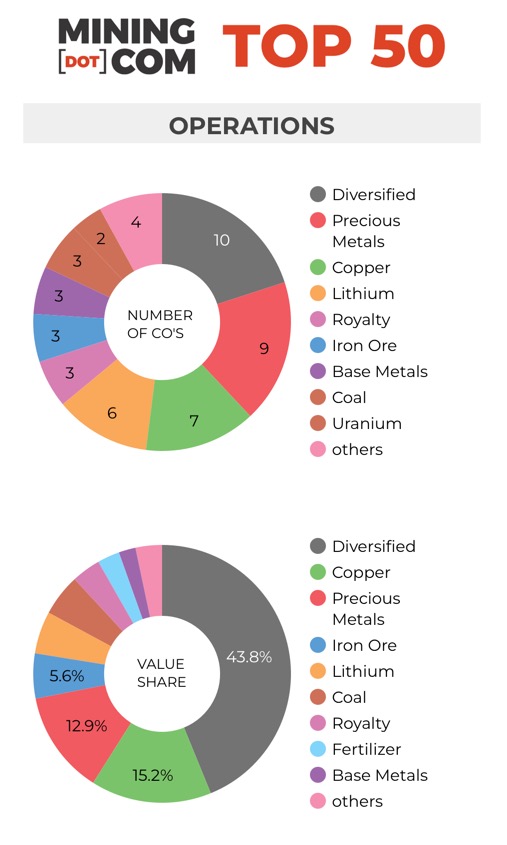

Over the course of 2023 gold and royalty companies on the MINING.COM TOP 50* ranking of the world’s most valuable miners added a collective $20.8 billion in market cap.

And judging by gold miners’ performance so far this year, gold above $2,000 is not providing enough support. Newmont is already down 17%, Barrick has shed 13% and Agnico Eagle shareholders are 9% poorer.

The number of precious metals companies in the top 50 has also been relatively stable over the years. With Newmont’s absorption of Newcrest now complete, the open slot was taken up by Kinross, which spent a few years in the wilderness.

Anglogold Ashanti was just edged out by Jiangxi Copper for position number 50 on the last trading days of 2023, but based on its performance so far in 2024 the London-listed company is already back among the top tier. Indeed Anglogold is the only major gold player in the black year to date.

Silver has not been able to ride gold’s coattails and the top 50 has not had a silver specialist for a few years after Fresnillo dropped out (now at #61) and while Pan American Silver has come close in recent years at the end of last year it made it to #58 only.

The exit of platinum and palladium majors like Sibanye Stillwater and Impala Platinum, now both valued at less than $4 billion, made space for Royal Gold to reenter at 47 at the end of last year, up from 57th in 2022.

After a dismal 2023, the sole remaining PGM specialist Anglo American Platinum looks likely to lose more ground this quarter as palladium and platinum prices continue to slide into the new year.

Not too tough at the top

London-listed Anglo American has had a rough year in part due to its exposure to platinum group metals and control of AngloPlat, and is now valued at $30 billion after peaking at $70 billion in March 2021.

Were it not for the London-listed company’s iron ore operations, the 40%-plus slump in share value may have been deeper. Rumours that Glencore may be sniffing around now that the Swiss behemoth’s bid for all of Teck Resources has soured is also keeping Anglo from falling further down the rankings .

Investors in Anglo, with a history going back more than a hundred years on the South African gold and diamond fields, have had a particularly wild ride over the last few years. In January 2016, Anglo’s market cap fell below $5 billion after it came close to suffocating under a pile of debt.

Against expectations, iron ore seems to be holding above $120 a tonne, Chinese property bankruptcies and Beijing’s tepid stimulus response notwithstanding.

Iron ore’s resilience despite Chinese troubles has also kept the share prices of the other diversified majors, which make their fattest profits from the steelmaking ingredient, from skidding.

The top 10 mining companies have been able to keep their share of the total above 50% for a few years now. Not quite the magnificent seven, but size does matter in mining, particularly when access to capital is no longer a headache but a migraine.

Expectations of another active year of M&A in the sector is likely to make the Top 50 top-heavier, especially now that it’s painfully obvious just how one-commodity companies like the lithium stocks can so easily be derailed. Coal miners’ strong 2023 suggests there are still exceptional minerals that prove the rule.

Lithium losers

After defying gravity early on, the combined losses for lithium miners in the top 50 climbed to nearly $30 billion in market cap over the 12 month period. Four counters occupy the worst performance table for 2023.

The M&A drama surrounding Liontown, Albermarle and Hancock Prospecting turned out to be a soap opera and Chile’s move to take control of its lithium industry now appears far less consequential than feared.

Despite the precipitous decline in lithium prices in 2023, after hitting all time highs above $80,000 a tonne in November 2022, none of the battery metal miners’ stock performance was dire enough to drop out of the Top 50.

The merger of Livent and Allkem to form Arcadium Lithium could in fact up lithium mining’s representation in the ranking to seven should Pilbara Minerals’ January bleeding be stanched. But with lithium prices far from stabilizing, the battery metal’s presence in the top 50 may fade further.

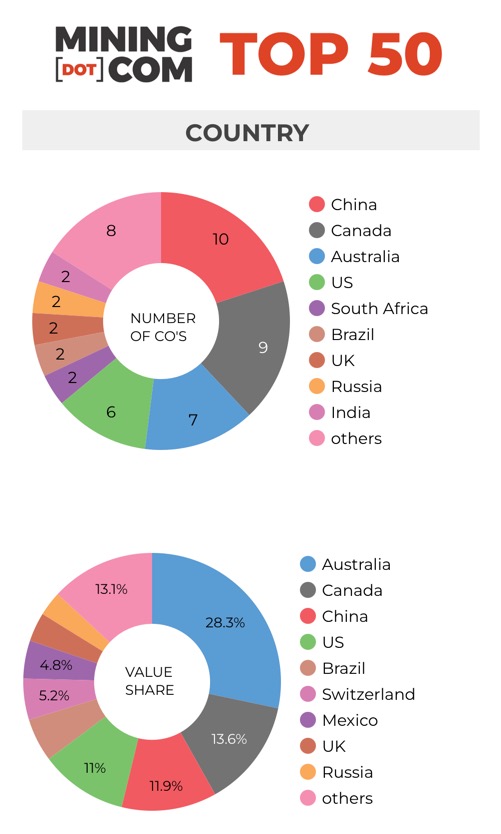

Pilbara Minerals, which unlike its peers was still able to show share price gains last year, joined the Top 50 last year, bringing the number of companies based in the Western Australia capital to five, surpassing the tally of Vancouver, BC as the top home base in the ranking.

With the exit of First Quantum, three mining companies in the top 50 call Vancouver home while the return of Kinross saw the ranks of Toronto-headquartered miners move back up to four.

Nuclear options

Uranium prices more than doubled during 2023 and recently hit triple digits for the first time in 16 years. The breakthrough for the nuclear fuel comes after a decade in the doldrums following the Fukushima disaster in Japan.

Canada’s Cameco made the best quarterly performer list once again in Q4 and after doubling in market worth in 2023. The Saskatoon-based company now sits at no 23 in the ranking after jumping 22 places since end-2022.

The value of shares in Kazatomprom, the world number one uranium producer, topped $10 billion at the end of 2023, placing it at position 38. Until last year the state-owned Kazakh company was outside earshot of the Top 50 since its dual-listing in London and Astana in 2018.

None of the smaller uranium companies are likely to pierce the top 50 by themselves, but combinations among the rank and file may edge in when countries aiming to ditch fossil fuels stop thinking they can have their yellowcake and eat it too.

*NOTES:

Source: MINING.COM, Morningstar, GoogleFinance, company reports. Trading data from primary-listed exchange at December 28 2023 to January 2, 2024 where applicable, currency cross-rates January 2, 2024.

Percentage change based on US$ market cap difference, not share price change in local currency.

As with any ranking, criteria for inclusion are contentious. We decided to exclude unlisted and state-owned enterprises at the outset due to a lack of information. That, of course, excludes giants like Chile’s Codelco, Uzbekistan’s Navoi Mining, which owns the world’s largest gold mine, Eurochem, a major potash firm, and a number of entities in China and developing countries around the world.

Another central criterion was the depth of involvement in the industry before an enterprise can rightfully be called a mining company.

For instance, should smelter companies or commodity traders that own minority stakes in mining assets be included, especially if these investments have no operational component or warrant a seat on the board?

This is a common structure in Asia and excluding these types of companies removed well-known names like Japan’s Marubeni and Mitsui, Korea Zinc and Chile’s Copec.

Levels of operational or strategic involvement and size of shareholding were other central considerations. Do streaming and royalty companies that receive metals from mining operations without shareholding qualify or are they just specialised financing vehicles? We included Franco Nevada, Royal Gold and Wheaton Precious Metals on the basis of their deep involvement in the industry.

Vertically integrated concerns like Alcoa and energy companies such as Shenhua Energy or Bayan Resources where power, ports and railways make up a large portion of revenues pose a problem. The revenue mix also tends to change alongside volatile coal prices. Same goes for battery makers like CATL which is increasingly moving upstream, but where mining still makes up a small portion of its valuation.

Another consideration is diversified companies such as Anglo American with separately listed majority-owned subsidiaries. We’ve included Angloplat in the ranking but excluded Kumba Iron Ore in which Anglo has a 70% stake to avoid double counting. Similarly we excluded Hindustan Zinc which is listed separately but majority owned by Vedanta.

Many steelmakers own and often operate iron ore and other metal mines, but in the interest of balance and diversity we excluded the steel industry, and with that many companies that have substantial mining assets including giants like ArcelorMittal, Magnitogorsk, Ternium, Baosteel and many others.

Head office refers to operational headquarters wherever applicable, for example BHP and Rio Tinto are shown as Melbourne, Australia, but Antofagasta is the exception that proves the rule. We consider the company’s HQ to be in London, where it has been listed since the late 1800s.

Please let us know of any errors, omissions, deletions or additions to the ranking or suggest a different methodology.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments