The oases that once interrupted the dusty slopes of the Atacama desert in northern Chile allowed humans and animals to survive for thousands of years in the world’s driest climate. That was before the mining started.

Sara Plaza, 67 years old, can still remember guiding her family’s sheep along an ancient Inca trail running between wells and pastures. Today she is watching an engine pump fresh water from beneath the mostly dry Tilopozo meadow. “Now mining companies are taking the water,” she says, pointing to dead grass around stone ruins that once provided a nighttime refuge for shepherds.

“No one comes here anymore, because there’s not enough grass for the animals,” Plaza says. “But when I was a kid, there was so much water you could mistake this whole area for the sea.”

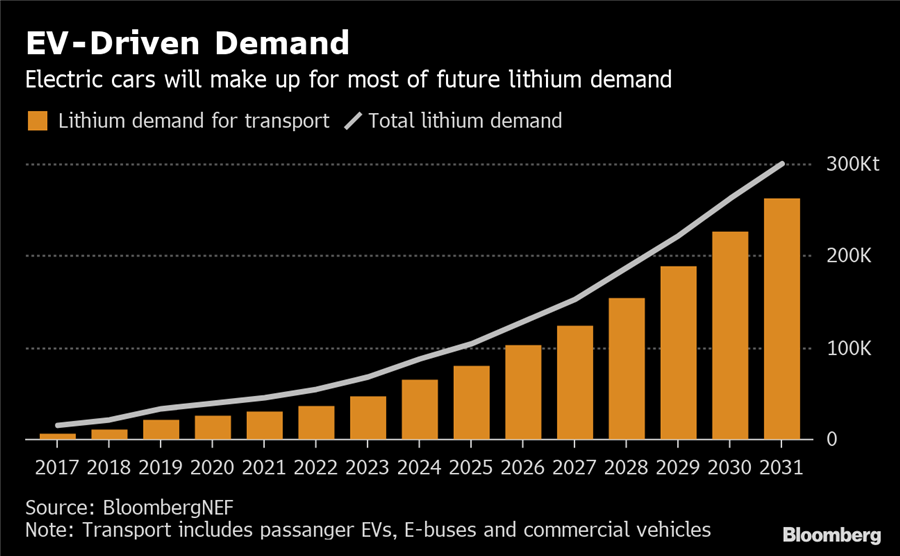

Atacama has become one of the busiest mining districts on the planet in the intervening decades, following discoveries of massive deposits of copper and lithium. In recent years that mining has intensified, thanks to booming demand for lithium, which is indispensable in the production of rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles. Chile exported nearly $1 billion of lithium last year, almost quadruple the export value from four years ago.

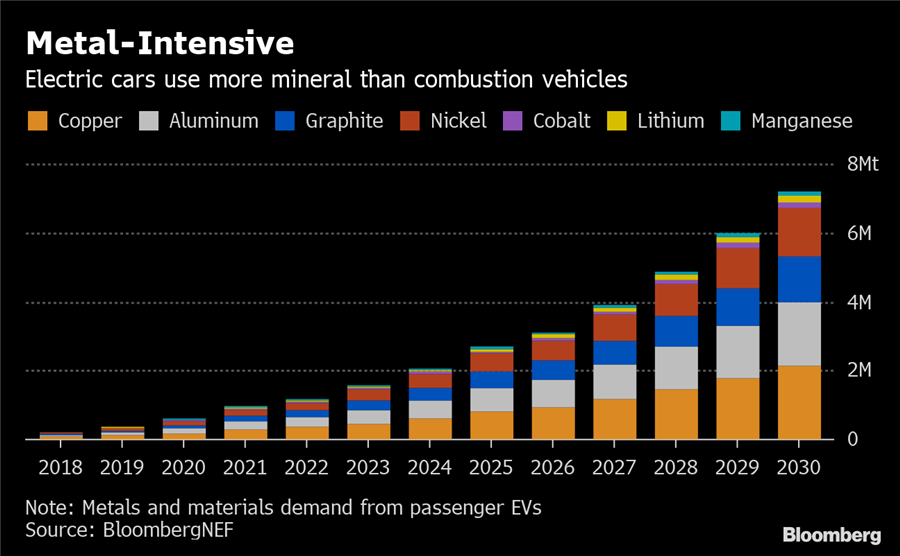

Pursuit of the soft mineral is often seen as something that’s good for the environment. Electric automakers such as Tesla Inc. want to make it easier and cheaper for drivers to adopt clean, battery-powered replacements for dirty combustion engines. Batteries are by far the most expensive part of an electric vehicle, so mining more lithium to meet rising demand helps lower prices. Putting more electric cars on the road is one of the most powerful ways to mitigate the effects of climate change, reducing the 15.6% of global carbon emissions that come from transportation.

But extracting Atacama’s lithium means pumping large amounts of water and churning up salty mud known as brine—and that’s having an irreversible impact on the local environment. Here, in this remote part of the Andes, the hopeful mission of saving the planet through electric cars is destroying a fragile ecosystem and depleting stores of drinking water.

“We’re fooling ourselves if we call this sustainable and green mining,” says Cristina Dorador, a Chilean biologist who studies microbial life in the Atacama desert. “The lithium fever should slow down because it’s directly damaging salt flats, the ecosystem and local communities.”

“The Chilean government is encouraging more and more companies to come here to explore and mine lithium, but they don’t have the capacity to oversee all of that”

Lithium mining’s crown jewel is a vast salt flat 10 times as big as New York’s Central Park. To get the minerals out requires working at an elevation about 6,500 feet above sea level. The otherworldly desert landscape is dotted with shallow lagoons in which flamingos nest amid an enclosure of volcanoes and mountains. The stunning geography is akin to a gigantic bowl.

Dorador studies the microscopic life found in the lagoons, which are fed by underground reservoirs and thin streams coming down the mountains. Over millennia, that water has deposited the coveted minerals at the heart of the salt flat. It has also been the key to sustaining life in a place so hostile that scientists use it to simulate conditions on Mars.

Mining companies have made a study of the water, too. The world’s largest copper mine, BHP Group Ltd.’s Escondida, pumps water from wells on the southern part of the salt flat; so, too, does Antofagasta Plc.’s Zaldivar copper operation. Copper miners use water at every step of the process to turn rocks into a 99.9% pure slab of mineral. Copper-rich rocks are crushed into a dust that’s mixed with water to flow through giant pipes, and then water mixed with chemicals is used to separate the copper from the slurry.

Lithium mining needs less fresh water but requires pumping large amounts of brine, the salty mud sitting below the crust of the salt flats. The mineral-rich brine is left in large pools to evaporate before processing. The world’s two largest lithium miners, Albemarle Corp. and Soc. Quimica & Minera de Chile SA, are currently extracting brine from the salt flat at unprecedented rates. Albemarle’s process is “absolutely clean,” a company official said in an email, and the company is developing technology to produce more lithium without pumping more brine than authorized. (SQM didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.)

Environmental impact studies conducted by the mining companies as part of the process to obtain government licenses consistently show no significant impact on water levels or wildlife. The government water authority, Dirección General de Aguas, which has no data of its own and monitors the salt flat through company reports, sees no risk of irreversible damage as long as legal requirements are fulfilled, said director Oscar Cristi.

The lack of government data or comprehensive independent research has made it hard to dispute statements from miners in the past. But recent studies and the testimony of local residents point to rapid deterioration.

From 2000 to 2015, the amount of water pumped out of the salt flat was 21% higher than the amount that filtered in, according to several reports by the Chilean government’s Committee of Non-Metallic Mining that analyzed data provided by mining companies. Water levels in some wells on the southern part of the salt flat declined by about one meter over the last decade in total. In the central part of the salt flat, levels dropped between 20 centimeters and 1 meter per year, on average, over the 15-year period covered by the data.

The falling water levels are felt by local people. Peine, the village closest to the mining, has license to pump 1.5 liters of water per second to supply 400 residents and a transient population of mine workers that can rise as high as 600. BHP’s Escondida copper mine has a license to pump 1,400 liters per second. Albemarle and SQM, the big lithium miners, have licenses to pump around 2,000 liters per second of brine.

The water allocated to homes in Peine often isn’t enough, forcing the local government to shut off running water at night so tanks can refill. During the height of summer, water cuts can last up to four days.

The Committee of Non-Metallic Mining reports tied decreases in water levels to the increase in brine pumping by the lithium miners. It also started to work on a model that would allow the government to independently monitor environmental changes. But when Chilean President Sebastian Pinera took office in March, his administration dissolved the committee.

Atacama’s infrequent rains and the highest solar radiation in the world—30% higher on average than in the Mojave desert—result in fast evaporation and allow miners to produce high-quality lithium at a low cost. But that method of mining, dating from the 1950s, results in the loss of large amounts of water. Companies and scientists are investigating ways to eliminate evaporation pools by capturing the lithium via chemical processes and then re-injecting water back into the salt flat, but these technologies haven’t reached commercial implementation.

Meadows and lagoons in the southern part of the salt flat have shrunk over the last few years, and the flamingo population has declined, according to the Atacama People’s Council, the umbrella group representing the 18 indigenous communities living around the salt flat. “Every company has their own studies, which are fully compliant with the rules,” says Francisco Mondaca, the council’s coordinator for environmental issues. “The problem is that the rules are weak. Water, flora and fauna are measured separately, so we don’t know how a change in one impacts the other.”

Local communities want to change that, and last month the council set up its first monitoring station in a lagoon on the salt flat. The installation will continuously monitor water levels, as opposed to the once-a-month measurements that mining companies do. There are plans to build 14 additional stations over the next year.

From 2000 to 2015, the amount of water pumped out of the salt flat was 21% higher than the amount that filtered in, according to reports

“The Chilean government is encouraging more and more companies to come here to explore and mine lithium, but they don’t have the capacity to oversee all of that,” says Sergio Cubillos, president of the indigenous council. “People need to realize that there’s an environmental cost associated to lithium, and that cost is being felt here.”

BHP has vowed to completely stop using fresh water in Chile by 2030 and has so far invested $4 billion in desalination plants. But the company is now requesting an extension of its water rights from 2020 to 2030, promising to cut the pumping rate to 640 liters per second. Monitoring hasn’t shown environmental changes different than those anticipated under existing permits, a company official said in an email. Antofagasta’s Zaldivar copper mine is also seeking a new license to pump 213 liters per second through 2029; the company wasn’t immediately available for comment.

The huge increase in lithium demand is drawing additional mining companies into the Atacama and other salt flats in the Andes. About 40% of Chile’s salt flats are now being explored for lithium, according to Dorador, the scientist. If the current way of mining continues, she warns, there’s a risk that the salt flats will run out of water.

This has happened before: Dorador points to the Lagunillas salt flat, significantly impacted after more than a decade of pumping by BHP’s Cerro Colorado mine. Also drier because of mining activity are the Punta Negra salt flat near BHP’s Escondida and the Michincha salt flat near the Collahuasi copper mine, which is owned by Anglo American and Glencore.

The Atacama salt flat is the largest in Chile, meaning any changes there will happen slower, but it could share the fate of other salt flats, says Mondaca of the indigenous council. He cautions that mining companies’ assessments of the environmental impacts don’t account for warming temperatures, which could accelerate the drying process.

“Climate change is just making this problem bigger,” Mondaca says. “Mining companies say the impact of what they’re doing now will not be felt for another 20 years, but with climate change that could be 10 years, or it could be five. No one knows.”

This could be the ultimate irony of the green revolution spurring demand for electric vehicles and batteries made from lithium. Scientists have come to view the fragile environment of Atacama as key to understanding the origins of life and the effects of climate change. Millions of years ago, the salt flat was a lake that has been slowly drying up, a process similar to what could happen elsewhere around the planet as temperatures rise.

“It is a picture of how our lakes will look like in the future,” Dorador says. To her, pumping water out of this dying ecosystem means taking away its last breath before scientists have had the chance to fully understand it.

(By Laura Millan Lombrana)

Comments