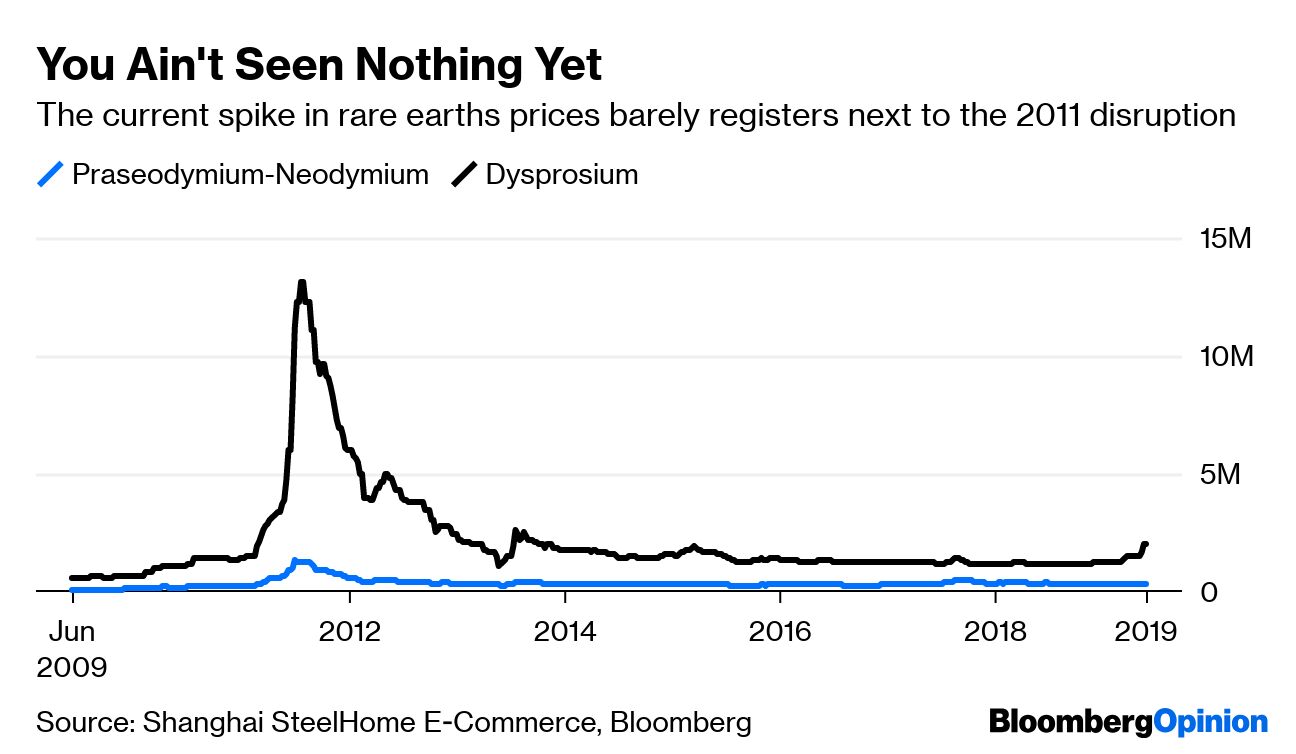

Once every decade or so, the world goes through a collective freak-out about rare earths.

The suite of 17 elements strung toward the bottom of the periodic table are notable in that they’re essential in several high-technology applications such as wind turbines, electric cars and lasers, and largely made in China.

That makes them a scary-sounding weapon in economic and diplomatic disputes. Back in 2010, China cut off exports of the minerals to Japan when the two governments were in dispute over ownership of some islands east of Taiwan. Now, state-owned Chinese media have been clamoring to do the same again in the trade war with the U.S. “If anyone wants to use products made of China’s rare-earth exports to contain China’s development,” the Global Times quoted an unnamed official as saying, the Chinese people “will not be happy with that.”

The truth, however, is that rare earths are a paper tiger. As we wrote last week, the 2010 case backfired spectacularly for China. Fearful of being caught short again, Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corp. – a government agency – went in with trading house Sojitz Corp. to provide a series of development loans to Lynas Corp., an Australian company looking to build a rare-earths supply chain outside China.

The first loan, at an interest rate of around 3% (1), was astoundingly good value for a company that wouldn’t post operating cash flow for nearly five years. Australia’s Fortescue Metals Group Ltd., the world’s fourth largest iron-ore producer that was then getting operating margins in the region of 50%, had to pay as much as 8.25% at the time for its borrowings in the U.S. junk bond market.

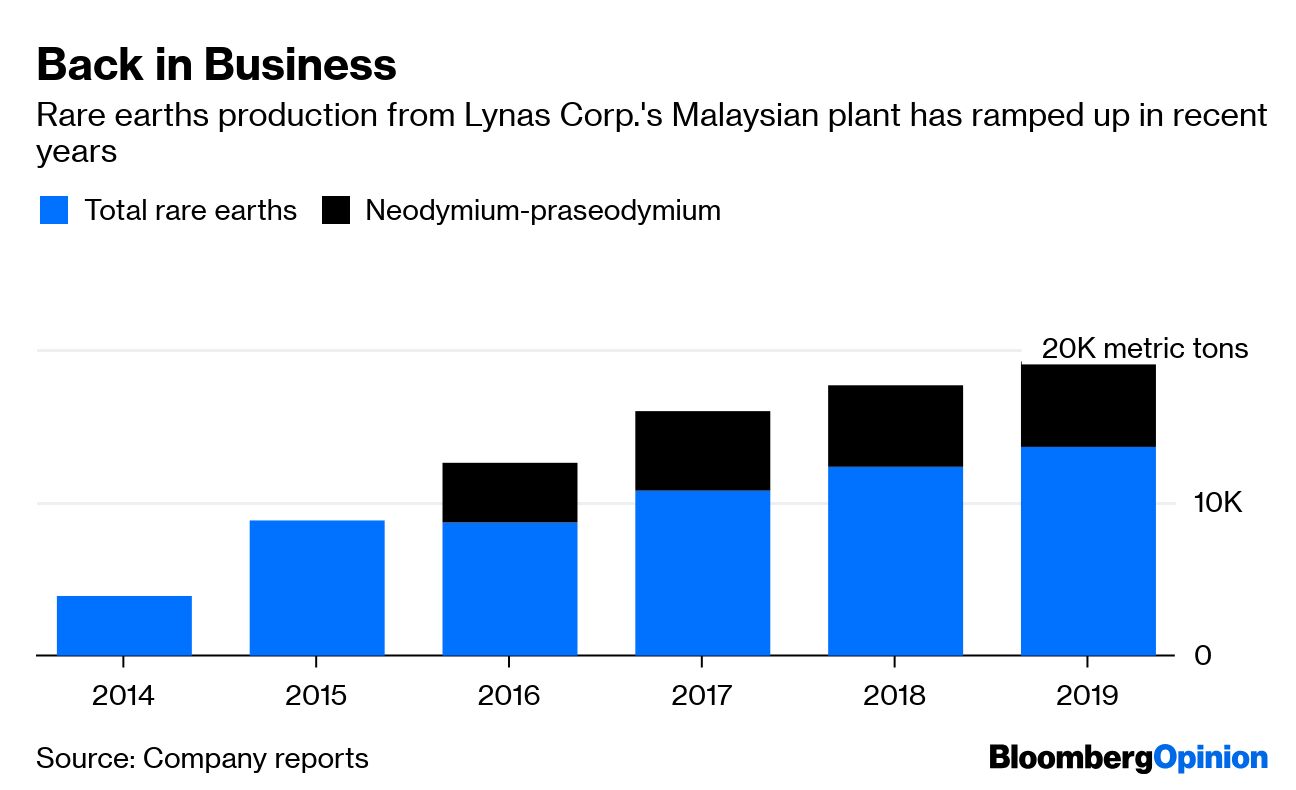

The result worked out well for all three players. China’s share of rare-earths production has fallen from 97% of the world’s supply in 2010 to around 71% in 2018. Lynas is now the second-biggest producer globally of neodymium-praseodymium, two rare earths crucial for making high-strength magnets, with about a quarter of the global market. Its sales agreement to Sojitz alone represents about 30% of Japan’s rare-earths demand.

China’s share of rare-earths production has fallen from 97% of the world’s supply in 2010 to around 71% in 2018

Lynas’s American cousin was less fortunate. Molycorp Inc. sought to turn the Mountain Pass mine in the Mojave desert into another non-Chinese source of rare earths, but things fell down – and down – over financing its roughly $1.7 billion in capital expenditure. An application for a $280 million loan guarantee from the U.S. Department of Energy was unsuccessful; $650 million in senior secured notes were issued at 10%, and Molycorp then had to seek another $400 million of support from distressed-debt fund Oaktree Capital Group LLC. Ultimately, the whole thing ended in bankruptcy court, and Mountain Pass is now owned by two U.S. funds and Leshan Shenghe Rare Earth Co., a Chinese rare-earths processor.

All that investment wasn’t a complete waste, though. While Mountain Pass’s new owners now export semi-processed ore for refining in China, full processing is due to restart in California by the end of next year. Lynas, meanwhile, last week signed a joint venture agreement with Blue Line Corp. to build a rival plant in Texas. If there’s anything that’s going to accelerate the shift to a wholly American supply chain, it’s the threat of a Chinese export ban (2).

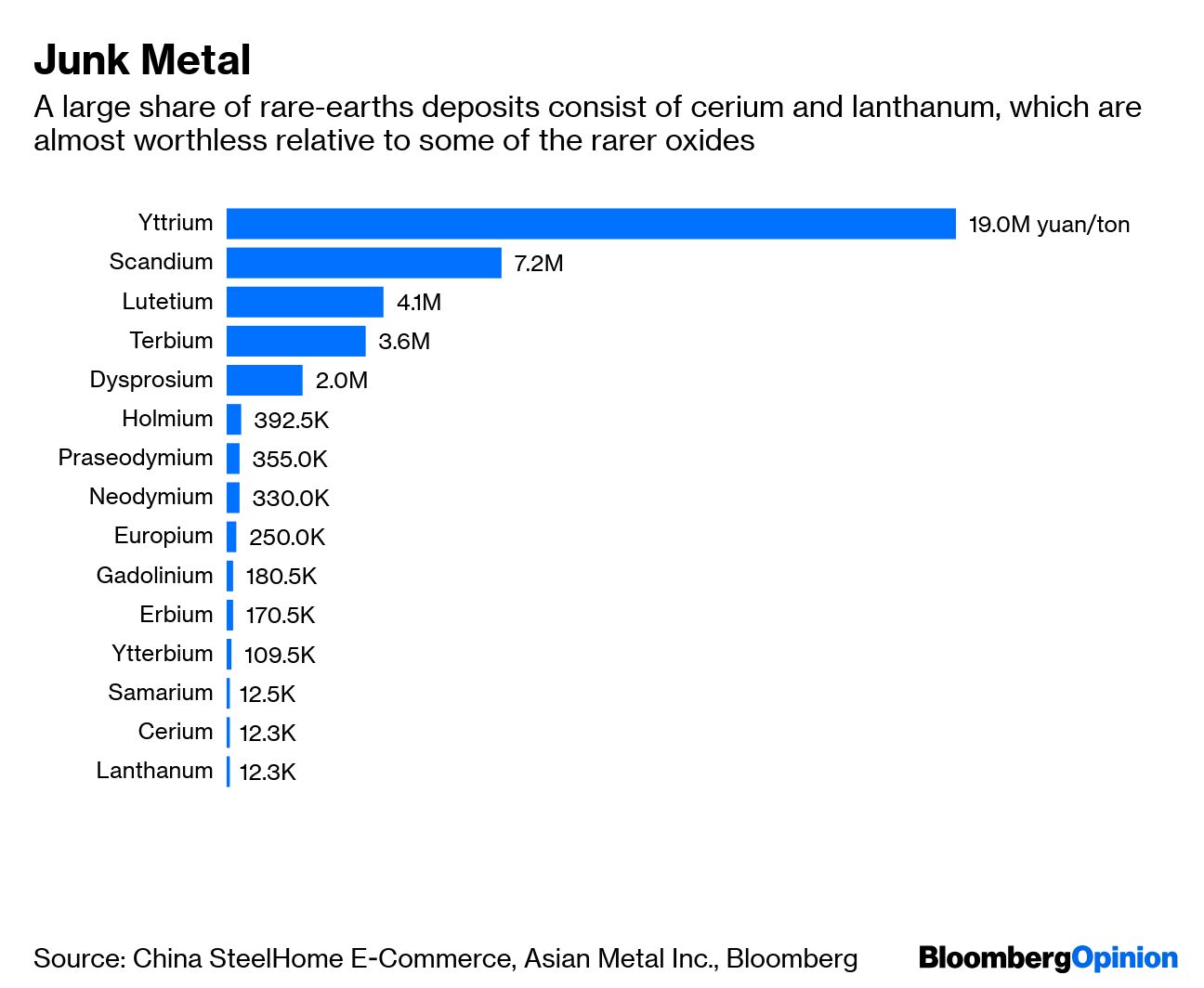

As is often pointed out, most rare earths aren’t in fact rare. Lanthanum and cerium are as abundant as copper and lead, and are used in such pedestrian applications as pool cleaner and cigarette-lighter flints. Even the more prized magnetic elements such as neodymium, dysprosium, praseodymium and samarium are humdrum enough that Apple Inc. uses rare-earth magnets to make its power cables stick in place. Pottery enthusiasts can pick up neodymium oxide for around $50 a kilogram online to give a blue tint to their glazes; that’s probably a bit more neodymium than you’d find in a typical electric car.

Supply is particularly generous when you set it against the most crucial and alarming segment of demand: military hardware. This amounts to no more than around 500 metric tons a year, according to a U.S. Department of Defense study, equivalent to what you’d get from Lynas’s plant in about 10 days. Solvay SA, a French chemicals company, recently set up a demonstration project to produce nearly 200 tons a year of rare earths just from recycling light bulbs.

The truth, however, is that rare earths are a paper tiger

In hindsight, the U.S. government might have been wise earlier this decade to provide the loan guarantees to put Mountain Pass on a more solid footing. It might also be sensible now to use some diplomatic muscle to encourage the China-skeptical government in Malaysia to resolve its current dispute with Lynas, which is currently a far bigger threat to diverse rare-earths supplies than Beijing’s saber-rattling.

Still, Washington’s relaxed approach to the 2010 flap was, in general, the right one. Supplies of rare materials are, by their nature, concentrated in a few countries. Unless we’re truly heading to an autarkic war-footing, those supply chains will continue to crisscross the globe. Most of us will barely have to think about them until the next panic breaks out.

(1) The rate on loan was in fact at 2.75% over U.S. dollar Libor, which was then hovering around 0.25%.

(2) There was also a major World Trade Organization case resulting from China’s 2010 export controls which Beijing lost — but in these times it’s safe to assume that, in extremis, neither side is going to let itself be constrained too much by WTO rulings.

(By David Fickling)