Australia is joining the growing number of nations looking to compete in space, from launching micro satellites that track sheep to mining water on the moon. Its advantage? Half the country already looks like Mars.

With advances in technology and the falling cost of launch slots, the fledgling Australian Space Agency, set up last year, is taking a commercial approach to extra-terrestrial ventures. It aims to leverage the country’s industrial skills in mining remote locations, developing automation and tapping a fast-growing start-up culture to triple the size of the sector to A$12 billion ($8.5 billion) by 2030.

Without deep pockets, Australia’s ambitious space projects will need to be commercial enough to interest businesses

“We’re witnessing a massive transformation of the sector, due to things like the miniaturization of technology, the lowering cost of launch and faster innovation cycles,” ASA Deputy Head, Anthony Murfett said in an interview. ASA aims to be “one of the most industry-focused space agencies in the world.”

It will need to be. The government budget for ASA is just A$41 million for four years, compared to NASA’s annual $20 billion and the European Space Agency’s 5.7 billion euros ($6.4 billion). Without deep pockets, Australia’s ambitious space projects will need to be commercial enough to interest businesses.

Andrew Dempster, Director of the Australian Centre for Space Engineering Research at the University of New South Wales, is focused on reducing the investment risk for big resources companies like Rio Tinto Group in a proposal to mine water on the moon.

“What’s preventing them from participating at the moment is that the risks that are there are not risks they have dealt with before,” said Dempster. So as well as tackling the engineering challenge, his team needs to make a compelling business case.

Rio said in a January report that it was engaging with the industry to see how its mining technology could be used in space, in particular its use of autonomous drilling. ASA head Megan Clark is a non-executive director at Rio.

Moon water could be a potential source of rocket fuel to enable manned missions to Mars in the long-term. “Getting things from the surface of the Earth into orbit or into deep space costs a lot of money,” said Dempster. “If you can produce water in space for less than it costs to get there, then you’re ahead.”

Woodside Petroleum Ltd., Australia’s biggest listed oil and gas producer, partnered with NASA to use robot technology to improve safety at its offshore platforms

Lunar exploration is becoming increasingly crowded. China in January landed the first vehicle on the far side of the moon, Israel’s privately funded Beresheet probe is on its way there and an Indian lander and rover are due to launch this month. The European Space Agency has said it plans to start mining water on the moon by the middle of the next decade. Dempster’s goal is to send a mission there within five years, citing the proliferation of private companies like SpaceX that are making space more easily accessible.

Some Australian resources companies are already adapting terrestrial technology for space. Woodside Petroleum Ltd., Australia’s biggest listed oil and gas producer, partnered with NASA to use robot technology to improve safety at its offshore platforms. Woodside will also collaborate with ASA to apply its expertise in remote operations to the space sector.

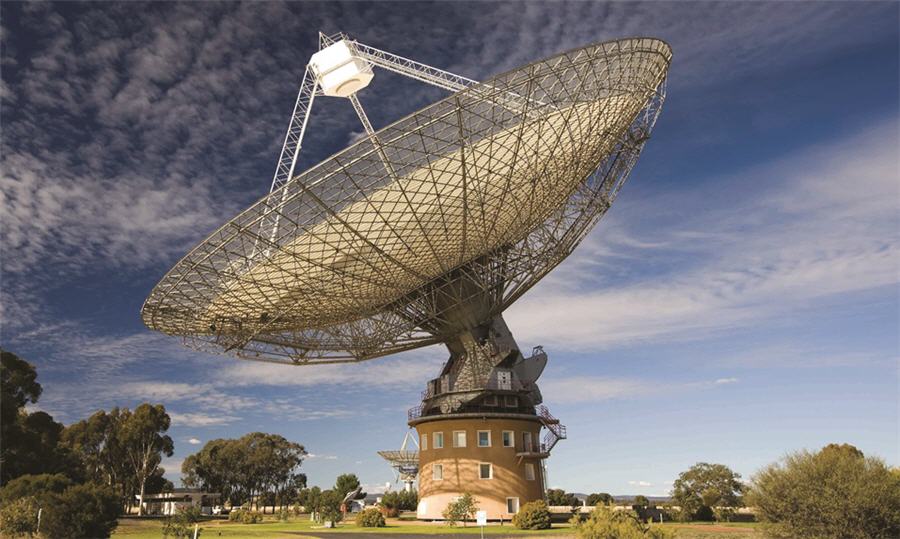

While ASA is less than nine months old, Australia’s cosmic ambitions go back to the earliest days of the space race. It was one of the first countries to launch a satellite from its own territory, sending a probe into orbit from the Woomera military site as early as 1967. And when Neil Armstrong made the first moonwalk two years later, it was Australia’s Parkes Radio Telescope that picked up the TV signals for most of the transmission that was broadcast to the world.

The vast, scarcely-populated outback has long been a mecca for astronomers thanks to its low light pollution and southern-hemisphere vantage point. The Sliding Spring Observatory 350 kilometers (217 miles) north of Sydney houses some of the most powerful telescopes in the world.

Today, most commercial opportunities for the county in space remain in the area of communications and remote sensing satellites.

Central Queensland University is leading a project which uses satellite positioning to track the movements of individual sheep or cattle to enable fenceless farming. Adelaide-based Myriota is trialing sensors for marine drifters in the ocean that would connect to a satellite network and provide precise data on currents, sea surface temperatures and barometric pressures — a trove of information for agencies and governments seeking to manage fragile marine eco-systems and predict major weather events such as El Nino.

Sky and Space Global Ltd., which listed on the Australian stock exchange in 2016, plans to launch a constellation of around 200 nano-satellites, each weighing less than 10 kilograms. that would provide another global communication network for voice, data and instant messaging.

Dempster says that the ability for startup companies to find commercial solutions like those are key to the growth of Australia’s space program.

“We’re not being weighed down by big lumbering agencies and huge multinationals,” he said. “There’s a lot of agile people with lots of interesting ideas working in this area. Success can occur quite quickly.”

(By James Thornhill)