Mark Bristow, known throughout the gold industry for his relentless focus on costs, is counting on his belt-tightening skills to take Barrick Gold Corp. to the next level.

“John really drove this business on multiple fronts, but his primary focus was the debt,” Barrick CEO Bristow said Wednesday in an interview at Bloomberg’s Toronto office, referring to the miner’s executive chairman, John Thornton. “He really pushed the envelope on cash flow.”

The “easiest’’ way to manage cash flow is to increase the grade of the gold being mined, Bristow said. “You go to the high-grade zones, and you mine them, and you get your cash flow.” However, that approach has its limits; the next step is to cut costs sufficiently that lower-grade gold becomes profitable — which also boosts reserves, he said.

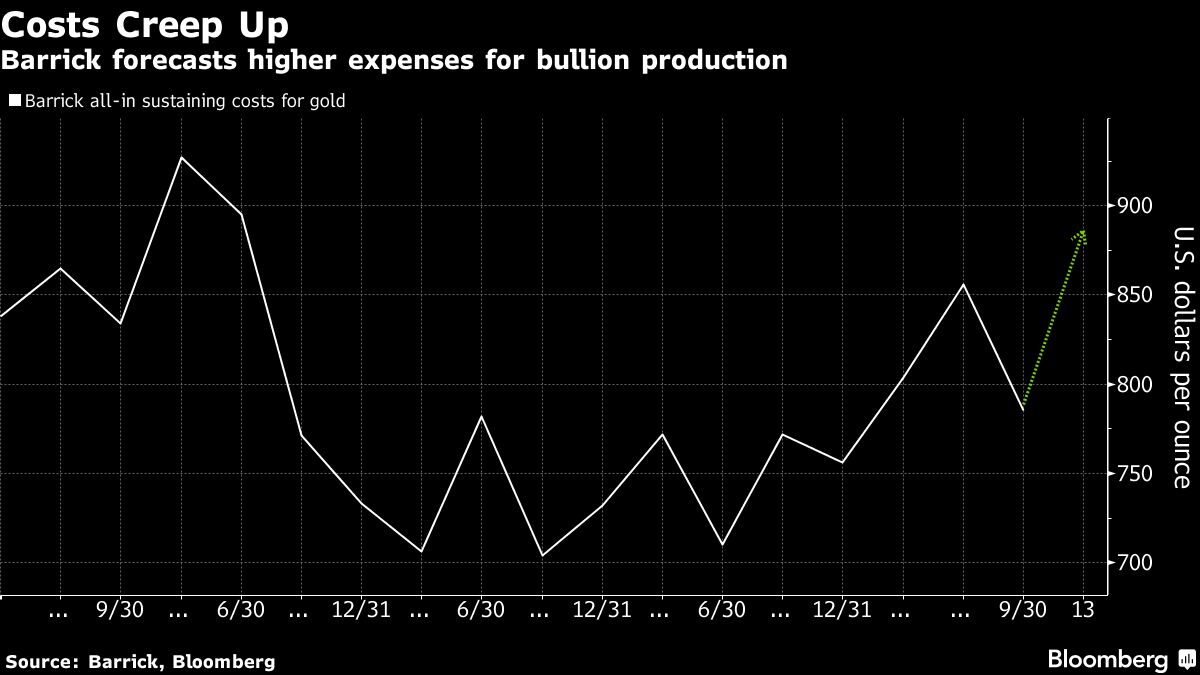

Last year, Barrick backed away from a goal, announced in 2016, of reducing all-in sustaining costs to $700 an ounce, citing inflation and falling production as headwinds. Now that Barrick has completed its $5.4 billion merger with Randgold Resources Ltd., Bristow said there is “every indication” that the new company’s costs can move toward that goal.

Bristow has said he intends to sell some Barrick assets to improve the portfolio, but declined to say whether those transactions will take place this year

Barrick, which released 2019 guidance on Wednesday along with its final fourth-quarter earnings as a stand-alone company, will provide more clarity on its five-year cost outlook later this year. But efficiencies at some of its top assets — its mines in Nevada and Pueblo Viejo in Dominican Republic — will drive the improvement, he said.

The transition from open pit to underground mining at Cortez Hills in Nevada is expected to be accompanied by higher costs this year. All-in sustaining costs are expected to be in range of $870 to $920 an ounce for the newly merged company this year, compared with $806 for stand-alone Barrick in 2018.

Andrew Kaip, an analyst at BMO Capital Markets, said in a note that the cost guidance was higher than he expected, and Barrick’s free cash flow of $37 million in the fourth quarter was below his estimate for $260 million.

Shares fell 2.8 percent to $13 at 11:05 a.m. in New York. The stock has slipped about 4 percent in 2019.

In Nevada, there is opportunity to shift to a margin improvement that is driven by cost cuts, Bristow said.

Digitization is part of that, as is more centralized control at the mine site. Whereas Thornton favored a decentralized model, in which more decision-making was done by mine managers, Bristow said he believes in “determined control,” by which he means a handful of more senior executives will call the shots from the ground. Bristow, who was CEO of Randgold, also favors managers he worked with at his previous company, noting that Barrick has replaced all of its minerals resource managers outside of Africa. “We’ve changed all the geologists.”

Barrick has cut its head office staff in Toronto as part of its restructuring — Bristow doesn’t believe in large head offices — and has overhauled the company’s senior management. Changes to the global team are now “done,” he said.

The job cuts have been controversial in Canada, where Barrick only has one operating mine, Hemlo, which is viewed as a strategic asset that offers a large tax shield. Earlier this month, Bristow said the asset would be sold if it couldn’t be made profitable, but that now seems less likely. “We’re going to deliver a profitable business at Hemlo, I’m convinced of that,” he said.

Bristow has said he intends to sell some Barrick assets to improve the portfolio, but declined to say whether those transactions will take place this year. With a raft of asset sales expected if the planned merger between Newmont Mining Corp. and Goldcorp Inc. proceeds, it might make more sense to put mines or projects on the market one at a time to keep prices high.

“We are working on disposal strategies and engaged with interested parties,” Bristow said. “We’ve got no real bleeders in the portfolio.”

(By Danielle Bochove)