Commodities love a tragedy.

Last week’s burst of a tailings dam at a Vale SA iron ore mine in Brazil’s Minas Gerais state has left close to a hundred, and possibly approaching 400, people dead. Far from wilting at the news, iron ore has been surging – up 12 percent in the last five days, its biggest five-day jump in about 18 months.

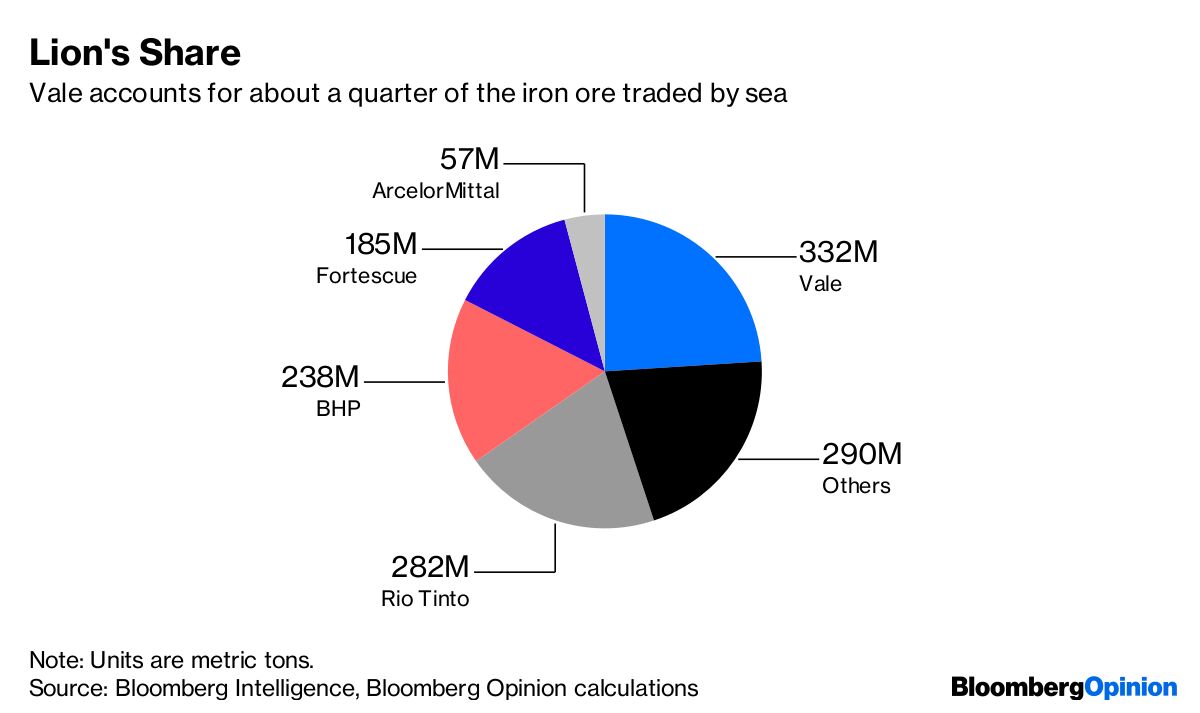

That seeming cold-heartedness is only natural. Vale produces about a quarter of the iron ore traded by sea. With the company announcing this week that it would close 10 similar dams, a considerable slice of the market – some 40 million metric tons – will be temporarily going off-line just as China’s post-Lunar New Year construction cycle kicks up a gear.

The pace of the freight-rate decline is highly concerning, and isn’t just the result of traditionally weak seasonal demand

Still, those inclined to make a bullish bet on disaster may be in for a dose of karma. This rally is more likely to collapse than extend.

For one thing, there’s the fact that 40 million tons isn’t all that much in the context of a seaborne iron-ore market that ships about 1.4 billion tons a year.

While Vale’s iron ore is uniquely prized thanks to its high iron content, the shuttered operations are also at its lower-quality pits. Product from the Vargem Grande and Paraopeba complexes has to be processed to turn it into salable pellets or blended with higher-grade ore from the Amazon before being shipped.

Vale’s prize asset, the S11D mine, is still running at barely more than half the full annual-production capacity of 90 million tons that it should hit next year, giving plenty of scope to make up the shortfall from other pits.The more important issue is what’s happening on the demand side, though. The Baltic Dry Index is a frequently watched measure of shipping costs, heavily influenced by the price of leasing the Capesize bulk ships that transport coal and iron ore. On Friday it fell to its lowest level in nearly two years, down almost 40 percent in the space of a month.

“The pace of the freight-rate decline is highly concerning, and isn’t just the result of traditionally weak seasonal demand,” Bloomberg Intelligence analysts Rahul Kapoor and Chris Muckensturm wrote Tuesday.

While profits at Chinese steel mills look to be rebounding because of a slump in the price of metallurgical coke, their customers appear to be having a harder time. Attempts to stimulate the industrial sector are misfiring, as my colleague Anjani Trivedi wrote last month, a fact underlined by Friday’s survey of factory purchasing managers by Caixin Media and IHS Markit, which posted the worst result since February 2016.

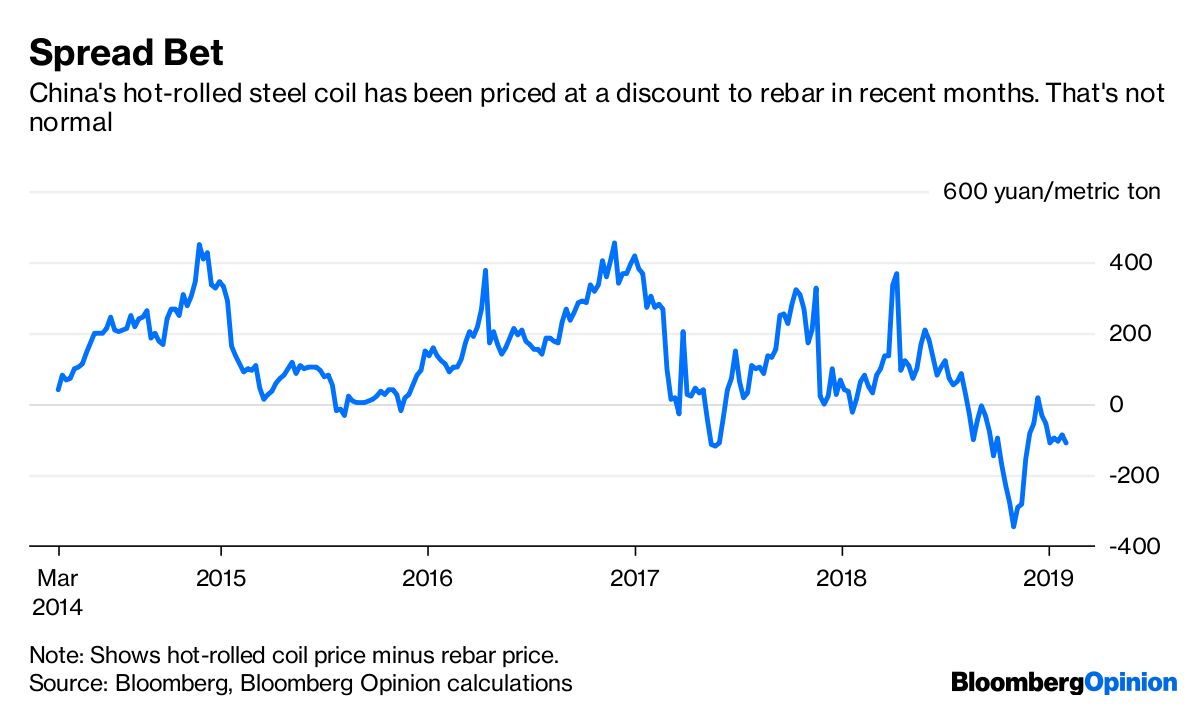

It’s also worth noting that the spread between rebar and hot-rolled coil should normally be positive, since the latter is of higher quality, used in consumer goods and vehicles, whereas the former is primarily for strengthening concrete. Yet it’s been negative now for three months. The overwhelming sense is still of a steel market that’s being propped up by spending on infrastructure and housing. Neither of those areas look set to catch fire soon.

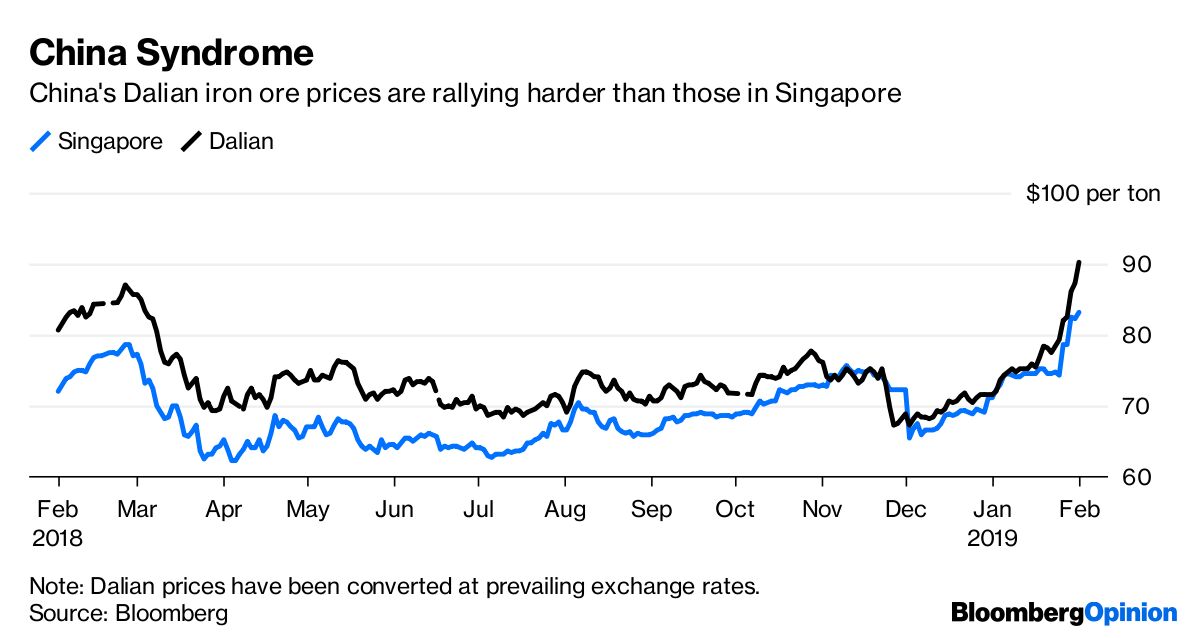

To be sure, Chinese investors if anything seem more bullish than those offshore about the current iron ore market. Futures in Dalian have risen, in dollar terms, even further than the Steel Index iron-ore contracts traded in Singapore, and started to climb before Vale’s dam disaster. It’s possible, then, that the extent of Beijing’s efforts to kick-start its slowing economy is only just being appreciated.

The more likely scenario is that prices trying to scale the hill of shrinking supply are ignoring the gulf of falling demand. This rally is living on borrowed time.

(By David Fickling)