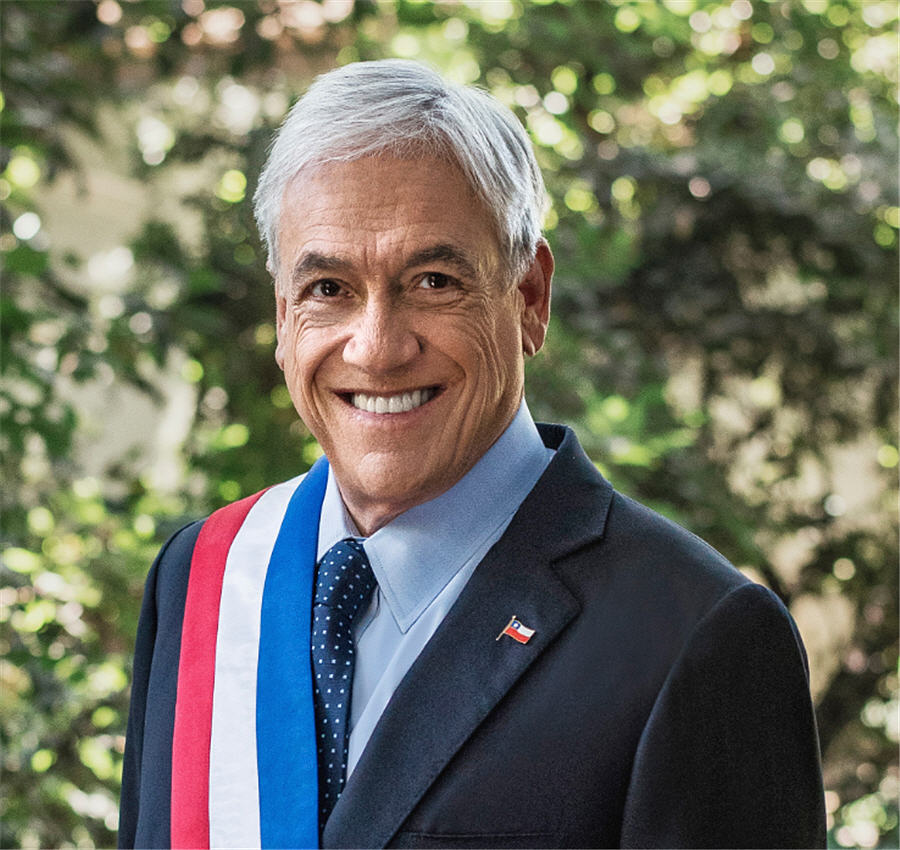

High expectations often come at a cost. For Chile’s President Sebastian Pinera, the second year in office looks to be riddled with challenges in keeping up with lofty promises of economic revival, passing important tax and pension reforms in a congress where he does not have majority, and unraveling redtape to stoke investment. Not to mention, the risk of the global trade war that would hurt copper prices, the country’s main export, while slowing down China, Chile’s main trading partner.

With the post-election honeymoon just about over, 2019 is the year Pinera must deliver. Below are key issues to look at next year:

Chilean citizens are still waiting to cash in dividends of Pinera’s election and promises of faster growth.

“The problem with Pinera is he is competing with himself, because of the incredible improvement during his first term,” Axel Callis, a political analyst in Chile, said in an interview. ”Next year, he will have to make good on his campaign promise for economic recovery so people can actually feel it.”

Pinera must pass these reforms through congress before the third year, when municipal elections begin and the government has its first political test

Growth in Pinera’s 2010-2014 first term averaged 5.3 percent. This year the economy is forecast to grow 4 percent and 3.5 percent next, compared to an average 1.7 percent of the second term of former president Michelle Bachelet, and investment is picking up. But consumer and business confidence have weakened and unemployment remains high (despite a debate on which job numbers to follow).

“There are still 2 to 3 percentage points of more self-employed people than before the last four years of slow growth,” Luis Oscar Herrera, an economist at BTG Pactual, told Pauta Bloomberg radio Dec. 13. “They want to join the labor market faster and that may weigh on salary growth and consumer expectations.”

All of this while the threat of a rekindled tariff war could produce a more pronounced negative effect, slashing chances of a true recovery.

Pinera’s government has hinged its growth prospects on a tax “modernization” and pension reform. However, both will have to pass through a divided congress in which the president has a limited ability to negotiate. A labor code reform and a law that should speed up environmental approvals for investments are also in the works. However, if the environmental approval bill passes in the next two years, it would be a big success, Joaquin Villarino, head of Chile’s mining council told Pauta Bloomberg radio Dec. 11.

“Pinera must pass these reforms through congress before the third year, when municipal elections begin and the government has its first political test,” Callis said.

Pinera’s popularity took a major blow in November after the death of a young man by police in the southern Araucania region rekindled an old conflict between the indigenous Mapuche population and the state. Protests took over from Santiago to southern Chile and his approval rating fell to its lowest since his term began in March, according to the Cadem poll.

With this panorama, Pinera will face losing more political capital in 2019 if he does not consolidate his reform agenda. Callis said Pinera is using other issues that have more play with the media, like migration, as a buffer for his popularity among the electorate, but that the effects are likely to be short-term.

“Most Chileans don’t have a problem with migration, as it’s really concentrated in only a few communities, but the retreat from the UN pact was used as a political statement,” said Callis. “After people forget about that, they will return to their original question: the economic promise.”

(By Daniela Guzman)