Woxna, situated about 160 miles (259 kilometers) north of Stockholm, was mothballed in 2001 amid a slump in prices. Now, a Canadian company called Leading Edge Materials Corp. is preparing to revive operations.

(Bloomberg) — The global race to develop batteries for electric cars is reaching deep into the pine forests of central Sweden, where a dormant graphite mine is getting a new lease on life.

Woxna, situated about 160 miles (259 kilometers) north of Stockholm, was mothballed in 2001 amid a slump in prices. Now, a Canadian company called Leading Edge Materials Corp. is preparing to revive operations.

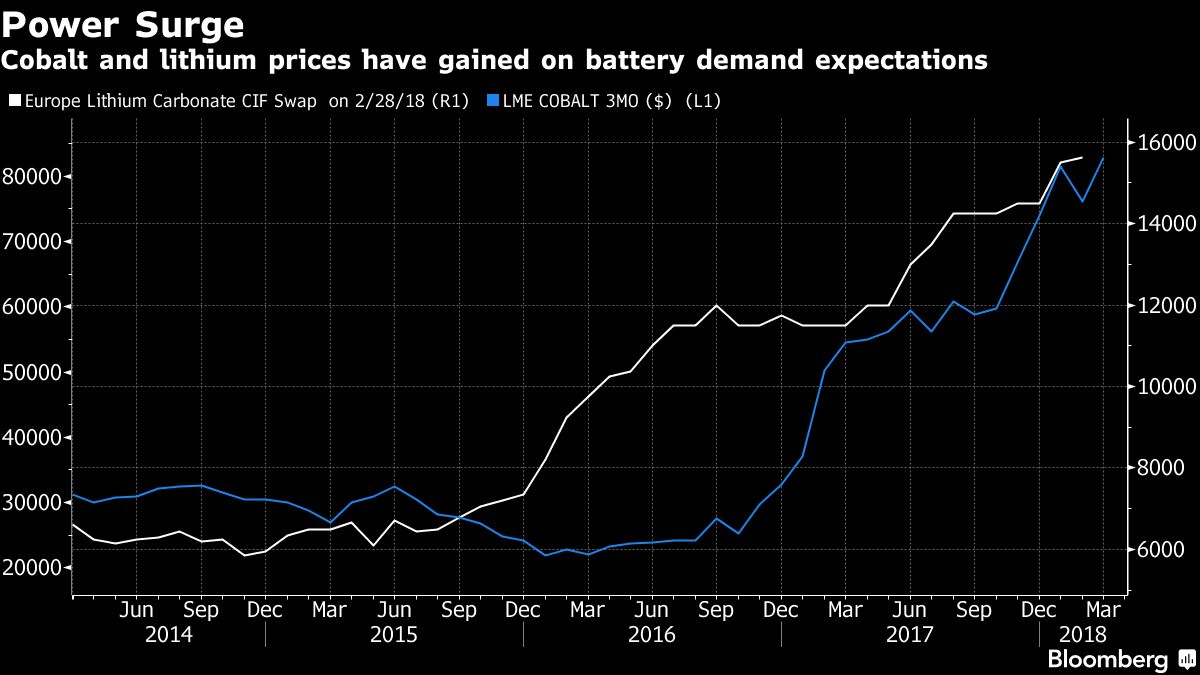

Though graphite has grabbed fewer headlines than other battery components like lithium and cobalt, whose prices have surged in recent months, the carbon material makes up a large part of the raw material costs.

Leading Edge’s push in Sweden is part of a wider trend in recent years of mining companies snapping up European permits as carmakers rush to develop electric models. Finland, Portugal and the U.K. have attracted prospectors. In addition to graphite, the Vancouver-based firm is also studying lithium deposits near Woxna, and has plans to go after cobalt in neighboring Finland.

The company wants to be a “one-stop shop” for battery manufacturers, according to Chief Executive Officer Blair Way. It’s testing a purified form of graphite from Woxna with the goal of making enough by 2020 to sell to battery-makers such as NorthVolt AB, which was founded by a former Tesla Inc. executive and plans to start large-scale output in Sweden. The miner has also held talks with car-makers including BMW AG.

“We’ve proven our graphite in the labs,” Way said in an interview. “We now have to produce enough so that these guys can take a big bag away and use it in their own cell production.”

A sustained shift to EVs would be the biggest revolution in the car industry since the invention of the internal combustion engine. The number of battery-powered vehicles is expected to rise to 530 million by 2040, from around 3 million today, and prices for key battery materials have jumped. Cobalt has tripled in the past 18 months, while lithium rose by about a third.

What’s different about graphite — which is widely used in the steel industry to insulate furnaces and has historically been exploited for pencils — is that it’s not a metal like lithium and cobalt and can be made synthetically. According to the Leading Edge CEO, a $20,000 battery pack for a Tesla contains about $1,200 worth of graphite, mainly of the synthetic variety. While the Palo Alto-based car maker doesn’t publicize component costs, whose prices fluctuate, its batteries are likely to also require about $1,300 worth of lithium and $800 of cobalt.

By replacing some of the man-made graphite with a purified natural form, according to Way, the cost could drop by as much as 40 percent. And by using renewable energy to cut emissions during the purifying process, the executive wants to position Leading Edge’s graphite as sustainable.

European industry executives and EU politicians have said they’re pushing for local development of batteries in order to crack dominance by China, which is expected to control supply chains over the next decade. Rio Tinto Group aims to start lithium production from its Jadar deposit in Serbia by 2023, and Sweden’s Boliden AB is currently considering whether to refashion its mine in Kylylahti, Finland, to focus on cobalt from copper, zinc and gold.

Securing raw materials is a “vital part” of the European Union’s efforts, even though they aren’t abundantly available in the region, according to Maros Sefcovic, the European Commission’s Vice President for Energy Union. To lower dependency on third country sources, the EU is promoting recycling and the use of substitutes, he said.

Finland has some of Europe’s largest reserves of cobalt, as well as facilities that refine almost 15 percent of global cobalt production, with most of the raw material currently imported.

“We have several known deposits, and there is certainly potential for finding new ores,” said Pekka Nurmi, Director of Science and Innovation at the Geological Survey of Finland. “There is a huge interest in battery metals from Finland.”

The miners’ plans are part of a larger blueprint for future European battery production, which is still in a nascent phase. German chemical maker BASF SE is planning a 400 million-euro ($492 million) cathode factory, South Korea’s LG Chem has said it will open Europe’s largest lithium-ion battery factory in Poland this year, and startup projects such as Germany’s TerraE and NorthVolt are underway.

“If the forecasts are correct then by 2020 we’d probably be able to supply meaningful amounts to those customers,” Way said. “If they should stumble along the way, we have to be careful that we aren’t ahead of them. The last thing I want to be is in production and not have a customer to sell to.”

(Written by Niclas Rolander and Jesper Starn)