From Africa to Australia, mining operations take place in some of the most challenging and inhospitable conditions on the earth. In the competitive race to provide these valuable resources to the world — whether its diamonds, coal or silver — some mining companies are doing everything in their power to maximize a global workforce through standardization techniques — but there is still much work to be done. Standardization in industrial terms means following repeatable actions to achieve consistent goals.

In this tightly knit community, word about innovation seems to travel fast because no one has time or money to waste. Counter to some professions, the older generation — geologists in their 60s, 70s and 80s — are highly coveted by mine operators for their successful methods to locate copper and coal in remote locations. How? By prowling ant hills, studying fossilized worm burrows and tracking termites, these old-timers have located major deposits.

These non-technical approaches are knowledge-based and have demonstrated business value in charting new territory — though most field camps rely on computers to manage large databases.

“Simplifying and standardizing the availability and access to data that feeds our scheduling and budgeting systems and the accessibility of systems that use our results, elevates their role and increases their reliability and dependability at mine sites worldwide,” said Andrew Lingard, RungePincockMinarco.

Another potentially bright spot in the global mining safety and standardization arena are the development of new ventilation systems for underground mines. Terradynamics believes the mining industry is expanding and they believe they can improve the efficiency of mines 35% amid increases in underground temperatures and ongoing concerns about production rates and safety regulations which apply in mines from Nevada to South America to Australia.

Global communication, too, can be standardized.

One way to ensure that standardization techniques are applied is through the use of consistent messaging throughout the mining environment. How do we convey messages? Among the ways are through documentation, websites and blogs. But when you’re a worker in a stifling Pretoria pit and you’re wondering where the core samples should be stored, you want to know and you want to know fast.

“I agree with that — particularly in less developed mining environments and geographies where human labor as opposed to automation is still the norm in mining. The relevant labor forces are usually poorly educated so visual communication tools are usually better understood then written documents,” said Dr. Gavriel Schneider, group director, Dynamic Alternatives Group.

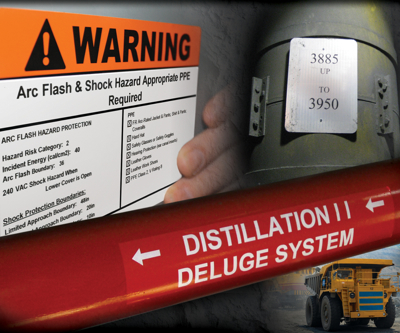

And that’s where signs, labels, pipe markers, valve tags, shadow boards and production boards get everyone on the same page for scheduling shifts, standard operating procedures, knowing where to go and who to contact in the event of an emergency and organizing the workplace for the best organizational structure.

Some techniques outside of obvious safety and maintenance signs and labels that are popular in the global mining community include:

Site-specific signs and labels can make all the difference for new hires and visitors, with messages targeted for that facility and those conditions. Generic signs just don’t cut it. Inspectors prefer labels and signs that are designed to inform and give clear instructions on hazards and operational procedures. Multilingual signs are often necessary to support the diverse workforce in the mining industry. This also depends on the location of the mine, but in many countries an array of nationalities and languages is the norm.

“I believe global standardization for multinational miners is important in terms of setting a minimum acceptable standard, particularly in terms of safety. But the push for standardization should not be considered more important than adapting to individual environmental challenges in different regions and countries,” cautioned Schneider.

“Workplace hazard communication, while important, is only one part of the many and varied risk control barriers that mining operations need to implement and maintain to ensure that hazards are controlled to acceptable levels,” added Andrew Hunt, technical director of Futuris Consulting. “A hazard sign or label should never be a substitute for hard infrastructure risk control barriers that eliminate a hazard or physically reduce the risk.”

Another area ripe for standardization is training.

In the United States, this year marks the 35th anniversary of the Mine Safety and Health Administration. Standard MSHA practices include 4x a year inspections at underground mines and twice per year at surface mines. MSHA also requires mine operators to provide training for new miners and annual safety retraining of miners during working hours and at normal compensation rates.

In Australia, companies like Global Mine Training develop business relationships with mining companies to encourage and train indigenous workers in open pit, underground, civil construction and road building. Remote training companies like Global 4WD are delivering site-specific training courses on vehicle recovery and defensive off-road driving.

The good news?

“Most companies and personnel working in different countries are generally willing to adopt and adapt new processes and technologies if they can see that it is a better way of operating and it provides financial and other benefits to the companies and personnel,” said Ken Jeffrey, finance director, Global Mining Services.

We still have a long way to go. Global operations are challenged with many different skill sets and levels, expensive equipment, huge investments and vastly different working conditions. A strictly cookie cutter approach might not work, but striving toward consistency and repeatable results will benefit all parties.