The Gold Report: Paul, your speech at the Hard Assets Conference in San Francisco was titled “Rational Expectations.” You spoke about monitoring the real rate of monetary inflation based on the total money supply.

Many goldbugs like gold as a hedge against Federal Reserve policies and high inflation. Paul van Eeden, president of Cranberry Capital, says he does not fear high inflation due to Fed policies. Van Eeden is a different kind of goldbug and in this interview with The Gold Report, he explains how his proprietary monetary measure, “The Actual Money Supply,” is the reason why.

The Gold Report: Paul, your speech at the Hard Assets Conference in San Francisco was titled “Rational Expectations.” You spoke about monitoring the real rate of monetary inflation based on the total money supply.

You take into account everything in your indicator that acts as money, creating a money aggregate that links the value of gold and the dollar. You conclude that quantitative easing (QE) is not resulting in hyperinflation and is not acting as a driver for the continuing rise in the gold price. What then is pushing gold to $1,700/ounce (oz)?

Paul van Eeden: Expectations and fear. It’s very hard to know what gold is worth in dollars if you don’t also know what the dollar is doing. When we analyze the gold price in U.S. dollars, we’re analyzing two things simultaneously—gold and dollars. You cannot do one without the other. The problem with analyzing the dollar is that the market doesn’t have a good measure by which to recognize the effects of quantitative easing.

Since approximately the 1950s, economists have used monetary aggregates called M1, M2 and M3 (no longer being published) to describe the U.S. money supply. But M1, M2 and M3 are fatally flawed as monetary aggregates for very simple reasons. M1 only counts cash and demand deposits such as checking accounts. M1 assumes that any money that you have, say, in a savings account isn’t money. Well, that’s a bit absurd.

TGR: What comprises M2?

PvE: M2 does include deposit accounts, such as savings accounts, but only up to $100,000. That implies that if you had $1 million in a savings account, $900,000 of it doesn’t exist. That’s equally absurd.

“If gold is money, we should be able to look at gold and compare gold as one form of money against dollars, another form of money.”

M3 describes money as all of these—cash, plus demand deposits plus time deposits, but to an unlimited size. One may think then that M3 is the right monetary indicator. But the problem with both M2 and M3 is that they also include money market mutual funds, a fund consisting of short-term money market instruments.

That’s double-counting money because if I buy a money market mutual fund, the money I use to pay for that mutual fund is used by the mutual fund to buy a money market instrument from a corporation. The corporation takes the money it received from the sale of the instrument and deposits it into its bank account, where it is counted in the money supply. I cannot then count the money market mutual fund certificate as money, as it would be counting the same money twice.

TGR: So there is no accurate indicator.

PvE: M2 and M3 double-count money; M1 and M2 don’t count all the money. All are imperfect measurements. That is why I created a monetary aggregate called “The Actual Money Supply,” which is on my website at www.paulvaneeden.com.

TGR: How is your measurement more accurate?

PvE: It counts notes and coins, plus all bank deposit accounts, whether they’re time deposits or demand deposits. This is equal to all the money that circulates in the economy and can be used for commerce—nothing more and nothing less.

TGR: How does that separate out gold from the dollar in value terms?

PvE: I’m a goldbug. I believe gold is a store of wealth and gold is money. If gold is money, we should be able to look at gold and compare gold as one form of money against dollars, another form of money.

Changes in the relative value of gold and dollars will be dictated by their relative inflation rates. If I create more dollars, I decrease the value of all the dollars. If I create more gold, I decrease the value of all the gold.

TGR: The relationship is determined by both quantitative easing and mining?

PvE: Correct. Essentially most of the gold that has been mined is above ground in the form of bars and coins and jewelry. We can calculate how much that is. That’s the gold supply. That supply increases every year by an amount equal to mine production less an amount used up during industrial fabrication. That’s gold’s inflation rate.

“If the Federal Reserve starts to see an increase in price inflation or a rapid increase in loan creation—monetary inflation—it can sell assets back into the market.”

We can also look at the money supply and see how it increases every year. That’s the dollar’s inflation rate. The value of gold vis-a-vis via the dollar will be dictated by these relative inflation rates.

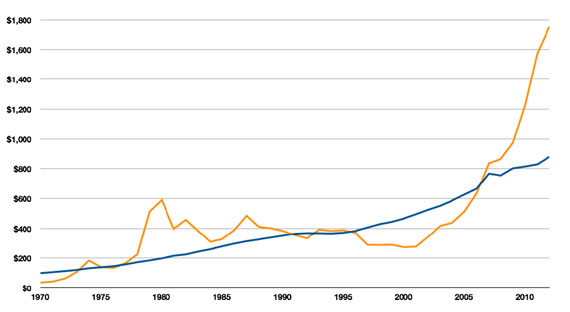

I have data on both gold and the U.S. dollar going back to 1900 and thus can compare the two. By doing that, I can calculate how the value of gold changes relative to the U.S. dollar and what gold is theoretically worth in terms of dollars.

Keep in mind that the market price is not the same as the value. In the market, price is seldom equal to value. Price often both exceeds and is below value. But it will always oscillate around value.

For example, in 1980, gold was trading much higher than value. By 1995, the gold price had sufficiently declined and U.S. dollar inflation had sufficiently increased to bring the gold price back to value, vis-a-vis the dollar. By 1999, gold was substantially undervalued. By 2007, it was again reasonably valued. But in 2012, it is again substantially overvalued.

TGR: The value of gold is not $1,700/oz?

PvE: No. The value of gold is about $900/oz. Expectations of monetary inflation are keeping gold prices high.

In 2008, after the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve Bank announced the first round of quantitative easing. The gold price started to rally because there was an expectation, with the Fed openly engaging in quantitative easing, that we would see massive U.S. dollar inflation. But that didn’t happen.

“Whether annual mine production goes up or down, it makes no difference to the price of gold.”

When the Fed engages in quantitative easing, it does so by buying assets in the open market, such as Treasury notes or bonds. When the Fed buys a government bond in the open market it creates the money to pay for it out of thin air. The payment is credited against a commercial bank’s account at the Federal Reserve Bank and is not available for commerce in the economy. It’s part of the monetary base, but not the money supply, as the money supply only counts money that can be used for commerce.

Thus, the money that the Fed creates is not in circulation. It’s not part of the money supply because it cannot be spent. The commercial bank in whose name it is credited cannot withdraw it. The only thing it can do is to create new loans against that reserve asset. But the bank can only create new loans equal to the demand for such new loans.

Right now, as a result of QE1 and QE2, there is an enormous amount of excess reserves on account at the Federal Reserve on behalf of these commercial banks. These excess reserves in theory could be used to create new loans. The reality is that new loan creation by commercial banks have proceeded at a very normal pace, and not at all at a rate that should cause fear of hyperinflation.

TGR: Is it that there isn’t a demand or that the banks don’t see creditworthy people to loan to?

PvE: It doesn’t matter; the result is the same. The point is that the marketplace is not creating those loans.

Money that is counted in the money supply is created when consumers and corporations borrow money from commercial banks. When a loan is created by a commercial bank, the banking system creates that money out of thin air just as the Federal Reserve created its money out of thin air.

When a loan is repaid, that money is destroyed. The natural increase of the money supply is the balance between loan creation and loan repayment from consumers and corporations to commercial banks. Their ability to create those loans is dependent, to some extent, on their reserve assets in the monetary base that they have on account at the Federal Reserve. Right now, those reserve assets are much, much larger than what is necessary to account for existing loans of banks. So banks have enormous capacity to create loans, but capacity to create is not the same as having created. We are not seeing runaway inflation in the market. The U.S. money supply is increasing at an annual rate of around 7%, which is high, but not high enough to cause the type of hysteria that the gold price is exhibiting.

TGR: The expectation that banks will eventually loan up to their lending capacity is what is causing the fears of hyperinflation and the gold price to go up.

PvE: That is correct.

TGR: When will banks start lending?

PvE: They are lending, which is why the U.S. money supply is increasing. But they are not lending at a torrid pace—the U.S. money supply is increasing only very slightly faster than the average annual rate since 1900, and slower than it was in the period from 2000 to 2009 before quantitative easing started. It is highly improbable that we will see the kind of monetary inflation the market is afraid of—the fear is misplaced.

The Federal Reserve alone controls the level of money in the monetary base. If the Federal Reserve starts to see an increase in price inflation or a rapid increase in loan creation—monetary inflation—it can sell assets back into the market. When those assets are sold back into the market the money that the Federal Reserve receives for the asset is destroyed. It evaporates.

Just as the Federal Reserve created money, it can destroy money. The Fed can absolutely prevent runaway inflation by selling assets back into the market, therefore constricting the ability of commercial banks to make loans.

TGR: If the Fed-created money isn’t loaned out, will the inflationary expectation in the market eventually disappear? Will the price of gold go to $800–900/oz?

PvE: That’s a possibility. The gold price rallied in response to QE1 and QE2 and when QE2 ended, the gold price started falling.

Prior to the announcement of QE3, the gold price rallied again in anticipation, but since QE3 has been announced, the gold price has been falling.

When the Federal Reserve announced QE1, there was a massive increase in the monetary base. When it announced QE2, there was another substantial increase in the monetary base, but much less than with QE1. But there hasn’t been an increase in the monetary base since the QE3 announcement. The Fed is “sterilizing” QE3 by offsetting sales of assets at the same time it is purchasing assets.

TGR: So the key is how the Fed implements quantitative easing?

PvE: Correct. The question is whether the gold market is rational in expecting hyperinflation or massive runaway inflation. That expectation is not being supported by the money supply, or by price inflation, or any other data. The only place the expectation is being manifest is in the prices of gold and silver.

TGR: If you look at the supply and demand expectations for gold versus the inflated valuation for gold, do you see more gold producers bringing gold out of the ground? If so, is that going to have an effect on the price?

PvE: If the gold price is high relative to production costs then yes, it does bring marginal mines into production, which increases the supply of gold. Incidentally, the increase in production from marginal mines then causes production costs to increase as well.

Does that have an impact on the price of gold? No. The reason is very simple. Approximately 1,000–2,000 tons of gold is traded each day. Annual production of gold is roughly 2,000 tons. If annual gold production increases by 5%, which is a lot, it’s 100 tons. We trade that in a couple of hours.

Whether annual mine production goes up or down, it makes no difference to the price of gold. The gold that’s trading globally is not just the gold that’s being mined; it’s all the gold that’s ever been mined, that’s sitting above ground in vaults and in storage. That’s where the price is set. Not on the margin of incremental production.

TGR: As you’re looking at the gold companies that are out there, are you seeing that we have some good prospects or are you seeing that the producers aren’t able to replace what they’re using and the juniors aren’t able to get the funding to find new sources?

PvE: I agree with your last statement. Producers are not able to replace their reserves. New exploration is not keeping up with reserve depletion and the juniors are not getting the funding to do the exploration.

The reason juniors aren’t getting funding is because the market has become quite risk averse. Junior exploration companies are among the most risky investments you can imagine. When risk aversion increases in the market, the ability of juniors to fund exploration evaporates.

It’s also true that the miners, particularly gold and copper, are having a tough time replacing reserves. Is that something that’s going to cause a calamity in the next 12 or 24 months? No. But, it is a reason why, over the long term, investing in mineral exploration is an interesting business. Without mineral exploration, there can be no mining industry and without a mining industry, our society does not function.

TGR: The last time we spoke to you, you said that you were very scared and that it was a healthy thing for investors to be scared because it keeps them from making mistakes. Are you still scared?

PvE: I’m definitely concerned that the market is going to look worse in 2013 than it looked in 2012. I think risk aversion is not yet ready to be replaced by risk appetite. The big concern I have for next year is further deterioration of the Chinese economy. In particular, a tipping point is being reached in China where its banking system can no longer sustain the bad loans it has created.

If economic growth in China takes a really big hit at the same time the financial problems in Europe have not yet been resolved, I see more risk aversion creeping into the market. That’s not good for junior exploration companies.

What makes me optimistic is that I think the worst is behind us in the United States. I think that slowly but surely the U.S. economy is going to get better and better. With time the improvement in the U.S. economy will bring risk appetite back into the market, but I don’t see that happening in 2013. We’ll have to see this time next year what the prognosis is for 2014.

TGR: In 2008, you told your investors to sell everything. Is that still your position?

PvE: The end of 2007 and the beginning of 2008 was the top of the market for most metals and certainly for mineral exploration stocks. That was the time to sell everything. Now we’re very close to the bottom of the market. It could be a long and drawn-out bottom but, nonetheless, I think that we’re close to a bottom.

This makes it a very good time to be accumulating mineral exploration assets or junior exploration companies. It assumes an investor has the patience and financial ability to wait for the next bull market and stay with the trades. Remember that junior exploration companies don’t generate revenue. If the bear market is protracted, these companies will need several rounds of financings in order to stay alive.

TGR: You also invest in silver, base metals and energy. Are some of these sectors doing better than others?

PvE: Copper, like gold, is very expensive. So is silver. The other base metals, such as aluminum, zinc, lead and nickel, are much more reasonably priced. Oil is also very reasonably priced at $85/barrel. I see less systemic risk in those sectors than I see in gold, silver or copper.

TGR: What specific companies do you like in those sectors?

PvE: I have recently acquired additional shares of both Miranda Gold Corp. (MAD:TSX.V) and Evrim Resources Corp. (EVM:TSX.V). I’m on the board of both of those companies and so I am not at all independent, or impartial.

I also recently acquired shares of a company called Millrock Resources Inc. (MRO:TSX.V). And I continue to scour the market for more opportunities. I intend to be a buyer of mineral exploration companies for the foreseeable future.

TGR: Why do you like those three?

PvE: All three of those companies share one element that is critically important. All have competent, experienced management and they have management that I trust: trust that they’re not going to squander the money that we give them and trust that they will use their best efforts to create shareholder value. It is my confidence in management teams that causes me to invest in mineral exploration. Mineral exploration is a business about ideas. It’s not about assets. And when you’re dealing with ideas, the asset that you’re de facto buying is people—it’s management.

TGR: You say that you’re doing this for the long term. How long do you think that you’ll have to wait?

PvE: Who knows? 5, 10 years? Maybe we get lucky sooner. Maybe we don’t.

TGR: Thanks for your insights.

Paul van Eeden is president of Cranberry Capital Inc., a private Canadian holding company. He began his career in the financial and resources sector in 1996 as a stockbroker with Rick Rule’s Global Resources Investments Ltd. He has actively financed mineral exploration companies and analyzed markets ever since. Van Eeden is well known for his work on the interrelationship between the gold price, inflation and the currency markets.

Want to read more Gold Report interviews like this? Sign up for our free e-newsletter, and you’ll learn when new articles have been published. To see a list of recent interviews with industry analysts and commentators, visit our Streetwise Interviews page.

DISCLOSURE:

1) JT Long of The Gold Report conducted this interview. She personally and/or her family own shares of the following companies mentioned in this interview: None.

2) The following companies mentioned in the interview are sponsors of The Gold Report: Millrock Resources Inc. Streetwise Reports does not accept stock in exchange for services. Interviews are edited for clarity.

3) Paul van Eeden: I personally own shares of the following companies mentioned in this interview: Miranda Gold Corp., Evrim Resources Corp. and Millrock Resources Inc. I am a director of the following companies mentioned in this interview and receive remuneration as a director from these companies: Miranda Gold Corp. and Evrim Resources Corp. I was not paid by Streetwise Reports for participating in this interview.