Bolivia steps up lithium dealmaking despite growing opposition

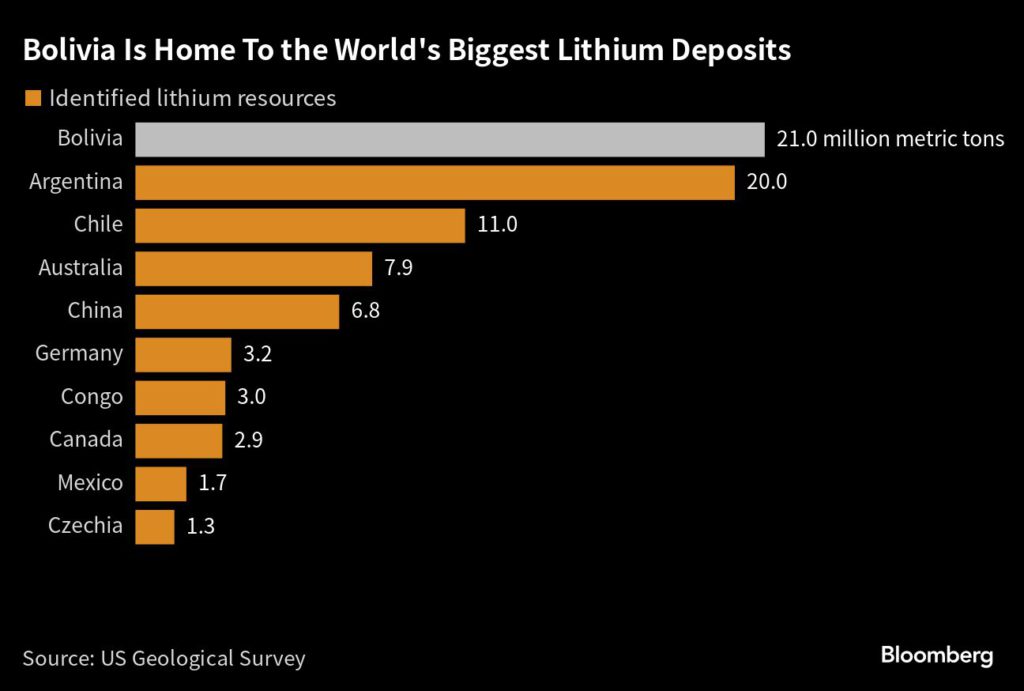

Bolivia is stepping up efforts to tap the world’s biggest lithium deposits, readying deals with new investors to build processing plants despite low prices and growing opposition from lawmakers and citizen groups.

The Andean nation opened its first industrial-scale plant in late 2023, built by a Chinese group, and last year signed deals for further investments with Russia’s Uranium One Group and a Chinese consortium, which are awaiting congressional approval.

“With the two new contracts, we plan to reach 49,000 tons of lithium carbonate annually within three years,” Omar Alarcon, president of state-owned lithium company YLB, said in an interview. “And we plan to send a new contract to Congress in the first quarter of the year.”

Authorities are negotiating contracts with European and Australian firms, he said in the Monday interview from La Paz.

Bolivia’s history of political and social unrest and a state-led approach to natural resources have been deterrents to private capital — as is a recent plunge in lithium prices in a glutted market.

For now, Bolivia’s contribution to global supply is negligible. While the landlocked country has much more resources than neighboring Chile, they aren’t yet deemed economically viable. Deposits suspended in brine under the remote Uyuni salt flat have high levels of magnesium, which make its lithium less pure and expensive to produce, and the nearest port is at least 500 kilometers (311 miles) and a border crossing away.

The government is betting on new direct extraction techniques to circumvent purity issues and shorten the path to production. A $970 million contract signed with Uranium One in September calls for construction of a plant with a capacity of 14,000 tons a year. Another contract, signed in November with China’s Catl Brunp and CMOC, involves a $1 billion plan to build two lithium plants that would churn out 35,000 tons a year.

Some civic groups, politicians and researchers say the contracts amount to sweetheart deals. Opposition lawmaker Juan Jose Torrez, from the highland city of Potosi, alleged a lack of transparency in the approval process and said royalties should be lifted to 11% from 3%. In recent days, a group of citizens marched against the contracts, while non-governmental organizations have called for Congress to reject them.

Alarcon dismissed those criticisms as politically motivated or misinformed. Bolivia will control the lithium sales and hold a majority stake in the ventures, he said, adding that YLB won’t begin to repay the investments until plants are running at full tilt, ensuring minimal financial risk for the state.

The nearly $2 billion in capital expenditure will be repaid in lithium carbonate to the Russian and Chinese firms as preferential buyers, over an average of 10 years, depending on international price moves, Alarcon said.

Although the contracts estimate a lithium price of $30,000 per ton, Alarcon noted that a price of at least $10,000 — more or less where prices are now — is necessary to ensure the plants’ commercial viability.

But Bolivia’s track record of lithium development is far from stellar. YLB’s first processing plant operated at just 17% of capacity last year and is projected to run at 23% this year, with no clear timeline for reaching full capacity.

The new deals are essential for Bolivia to finally realize its massive potential, Alarcon said. If they’re rejected, industrial-level production could be delayed by as long as 15 years.

“That would be catastrophic for the country,” he said.

(By Sergio Mendoza and James Attwood)

More News

US delays Canada, Mexico tariffs

The announcement comes a day after Trump gave a 30-day tariff reprieve to the big three automakers.

March 06, 2025 | 02:23 pm

Video: Seabridge CEO on KSM progress, questioned permits

The project, in the Golden Triangle of British Columbia, is one of the world’s top undeveloped gold deposits.

March 06, 2025 | 01:34 pm

Video: VRIFY’s new AI tool cuts exploration timelines from weeks to seconds

The platform provides real-time probability and variance metrics, which, VP says, challenges the old geological bias.

March 06, 2025 | 12:47 pm

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.excerpt }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments