Earlier this year, the Czech Republic’s central bank chief flew to London to have a look at a swelling stack of gold bars stored in the Bank of England’s concrete-encased vaults beneath Threadneedle Street.

Ales Michl’s mission to inspect the precious metal held for the Czech National Bank was part of the governor’s stated ambition to double the country’s stockpile to 100 metric tons in the next three years. It’s increased fivefold since he took office in 2022 with an aim to diversify the bank’s reserves.

“We need to reduce volatility,” Michl, who grew animated when queried on the subject, told Bloomberg Television earlier this month. “And for that, we need an asset with zero correlation to stocks, and that asset is gold.”

The Czech policymaker isn’t alone in accelerating bullion purchases. Peers from Warsaw to Belgrade are joining the gold rush as a way to diversify investments and bet on future price increases, making eastern Europe one of the biggest buyers of the metal and helping to drive the gold rally.

Central banks around the world are stocking their gold arsenals as a shield against external shocks such as prospective trade wars brought on by Donald Trump’s second presidency and geopolitical tensions in Ukraine and the Middle East. But eastern European monetary guardians have made a particular show of topping up their gold piles.

In addition to Michl’s foray to London, his counterpart in Warsaw has penned a movie script on the history of Polish gold. Serbian authorities hauled their stockpile held abroad home to keep it safer in Belgrade — and help cut storage costs.

Striving for a sense of security is a powerful motive in a region that’s been ravaged by Europe’s wars of the past — and that now finds itself next door to the continent’s deadliest conflict since World War II.

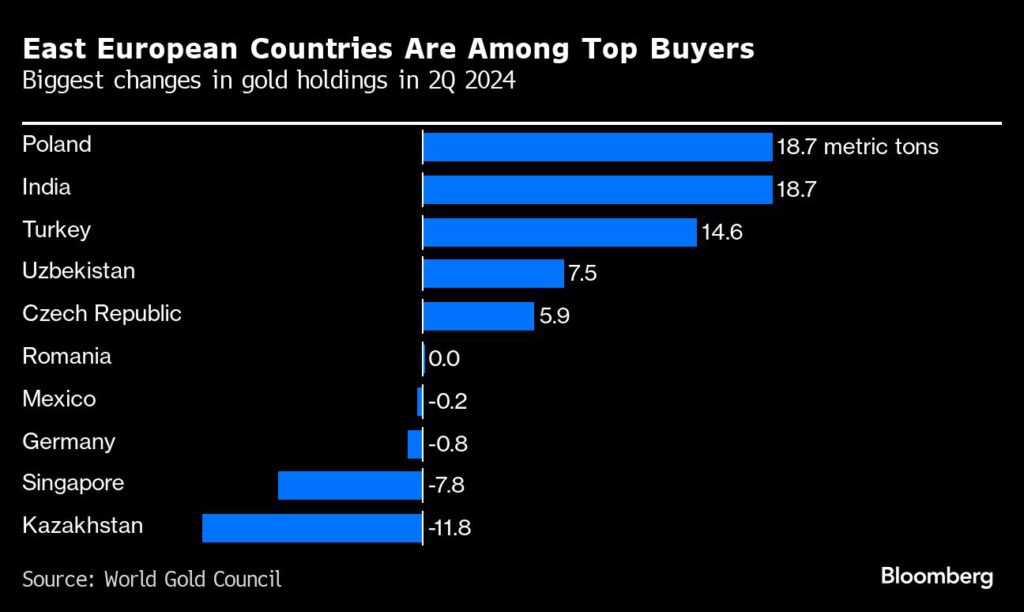

Poland, which shares a border with Ukraine and is a staunch supporter of Kyiv’s war aims, was the largest buyer of gold globally in the second quarter, according to the World Gold Council’s latest data.

Poland’s central bank governor, Adam Glapinski, said gold and hard currency reserves are crucial to protecting the economy against catastrophic events. He increased bullion holdings to some 420 tons as of September, about half the stockpile of India or Japan.

“We are entering the exclusive club of the world’s biggest gold owners,” Glapinski gloated during a news conference last month, reinforcing his aim to raise gold’s share to 20% of all reserves.

The head of the National Bank of Poland lamented having no time to work on his draft script. A YouTube video produced by the central bank in February shows Glapinski basking in a vault lined with sealed boxes of six thousand gold bars, intoning that the stash “is the property of all Polish people.”

The Czechs are also prospective club members. The central bank in Prague boasts about $150 billion in foreign reserves — nearly half of gross domestic product — one of the world’s biggest by proportion.

Michl, whose diversification drive includes US stock purchases, has confronted some criticism for buying gold as it reached a market record this year. Monetary officials have pushed back by insisting that the long-term purchases are gradual, reducing the impact of price volatility.

With the geopolitical winds churning, gold purchases have been a good bet for monetary policymakers. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. listed the metal among top commodity trades for 2025, saying prices could extend gains during Trump’s presidency and reach $3,000 an ounce by December next year.

“Geopolitical fragmentation is favorable for gold, while gradual dollar weakening should be a further tailwind,” Bank J. Safra Sarasin said in a report from Nov. 10.

For eastern Europe’s leaders, gold is viewed as a safe harbor — and a political selling point — as they maintain often complex balancing acts between the West, Russia and China. The Hungarian central bank has boosted its gold stash by more than a 10th to 110 tons this year.

The country’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban has relished being the EU’s chief disruptor with his ties to the Kremlin and Trump.

The central bank in Budapest has also lauded the metal as a safe haven. But gold has a role in the country’s historic identity.

The Money Museum, located in one of the palaces owned by the Hungarian National Bank, features a steam locomotive fashioned from yellow bars. The sculpture, called “The Rumble,” depicts the central bank’s staff, which fled the Soviet military at the end of World War II on a train loaded with gold reserves to prevent it from falling into foreign hands.

The associations figure no less in Serbia, where President Aleksandar Vucic, who like Orban holds a firm grip on power, had the country’s stockpile held outside the country repatriated in 2021. This year, he promised to buy bullion with “every surplus of money” that’s left in state coffers “to be safe and secure in hard times.”

Serbia’s central bank governor, Jorgovanka Tabakovic, has overseen a tripling of gold reserves to 48 tons since taking office in 2012. The accumulation was handled closely with Vucic, who provided the “strategic thinking, knowledge of global geopolitical relations and information” to back the gold purchases, she said.

“Gold is gaining value and importance in times of global turbulences, especially in geopolitical conflicts and periods of high inflation,” Tabakovic said in emailed response to questions. “Unfortunately, in recent years we’ve seen both factors at play.”

(By Peter Laca, Agnieszka Barteczko and Misha Savic)

Comments