Copper smelters are warning that plants may shut down or even go out of business if the industry’s processing fees drop too sharply, as annual supply negotiations with key miners get underway this week.

A wave of new smelter investments in China and elsewhere has left plants in growing competition to find enough ore to feed their furnaces, which means that miners can squeeze out increasingly attractive supply terms.

In private conversations, senior industry executives attending the annual LME Week said it’s likely that the key processing fee will fall to a level where smelters will struggle to turn a profit. The two sides began holding meetings this week to share their views on the market, although they have yet to put any numbers on the table, they said. There’s a broad expectation that the talks will be the toughest in years.

While the annual negotiations don’t get much attention outside of the metals world, this year the outcome could have far-reaching ramifications for the copper market. Smelter closures could reshape the map of global refined copper supply at a time of growing concerns about Chinese dominance over critical minerals. And, after a year in which the market for refined copper has been in oversupply even as miners struggled to lift output, the squeeze on smelters is likely to crimp refined supply — just as some expect China’s newly announced stimulus to kickstart consumption.

Smelters typically derive a large part of their profits from processing fees that are deducted from the cost of concentrates, the partly processed ore that they buy from miners. The industry agrees a benchmark for treatment and refining charges (TC/RCs) in the fourth quarter of each year — the fee is used as a reference for long-term supply contracts, while other ad hoc sales throughout the year are priced based on conditions at the time.

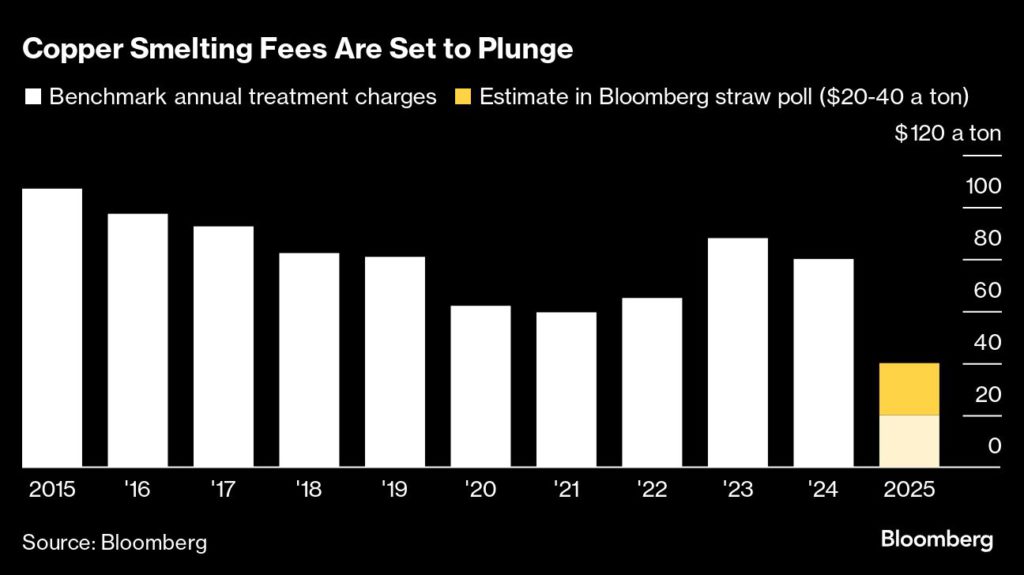

The mounting squeeze on ore supplies has led to a wide gulf between last year’s benchmark — which was set a $80 per ton of ore and 8 cents per pound of contained metal — and the terms being agreed in spot deals. The situation has grown so severe that the fees have turned negative; traders and smelters have been paying more for copper ore than the copper contained in it would fetch once processed, a highly unusual situation.

In a straw poll of more than two dozen miners, traders and smelters, respondents who provided an estimate said the benchmark would likely be agreed between $20 and $40 a ton and 2c to 4c a pound. Several respondents suggested that the negotiations could lead to a breakdown of the benchmark system, a potential watershed moment for the industry.

This year, the benchmark is expected to be negotiated with Chilean miner Antofagasta Plc, which in the past has tended to strike a tougher negotiating line than American rival Freeport-McMoRan Inc. The US company has often set the benchmark in recent years, but it will have far fewer concentrates to sell next year after building a huge new smelter next to its largest mine in Indonesia. Chief executive officer Kathleen Quirk said in an interview that Freeport won’t set the benchmark this year.

A spokesperson for Antofagasta declined to comment on the negotiations.

Representatives of Chinese smelters in London this week said they are emphasizing to Antofagasta that the industry already faces widening losses because there is not enough concentrate to go around, and warning that an aggressive cut to the benchmark fees could lead to production cuts and cause permanent damage to the industry. Officials at Chinese smelters said the industry would probably be lossmaking at fees below about $35 to $40 a ton.

“There’s been so much new capacity developed for smelters in China over the years, and there’s just not the concentrate available to feed everything,” Freeport’s Quirk said in London this week. “But for concentrate producers that are relying on smelters, they have to think: ‘Well, I don’t wanna push these guys out of business.’”

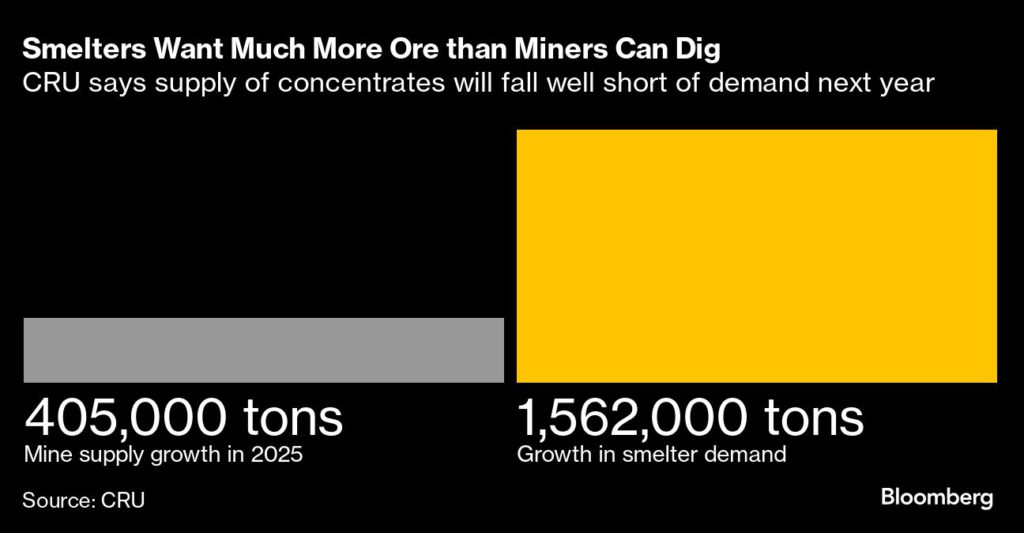

The huge mismatch between concentrate supply and demand stems from the commissioning of new plants in India, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as several major plant expansions in China. It’s also been a weak year for mine supply, but the rapid expansion in smelting capacity has fueled expectations that smelting margins will remain severely constrained even as mined output rebounds.

“We’ll maintain our production as we do have long-term supply contracts, and we’ll have to live with these lower TC/RCs for the coming year,” said Toralf Haag, who last month took over as CEO of Aurubis AG, Europe’s largest copper smelting group. “We’re optimistic that the situation will start to resolve itself over the coming year — some refining capacity will come off-stream, and some additional mining capacity will come onstream.”

Researcher CRU estimates that the difference between smelters’ needs and concentrate supply will balloon to about 1.2 million tons, the biggest deficit in at least a decade.

It expects that 70% of the gap will be resolved by smelters reducing their operating rates, but the remaining gap will need to be solved by temporary or permanent plant closures. And the more aggressive miners are in driving down TC/RCs, the more extensive the cuts will be, according to Erik Heimlich, the consultancy’s head of copper and zinc.

“Miners are in a very good position and they could force a very low TC/RC, but there are reasons that they won’t want to go as low as possible,” he said in an interview. “These are long-term relationships, and if you go very low, you’ll end up with an industry that loses a lot of players on the demand side.”

Read More: Mining industry struggles with valuation gap amid shift to copper

Comments