For a global lithium industry still reeling from gluts along the battery supply chain, the greater long-term risk is producing too little of the metal rather than too much, according to the world’s No. 2 producer, Chile.

More threatening than oversupply in the coming years is the risk of a renewed shortage, which would send prices soaring and make alternative battery technologies more viable, the South American nation’s finance minister said.

“Production needs to increase so that it remains profitable and attractive to manufacture lithium batteries for electro-mobility,” Mario Marcel said in an interview Thursday from his office in Santiago.

Chile intends to do its bit to make sure that doesn’t happen. This week, the government unveiled a list of salt flats that will be opened up to mining as part of a plan to double output over the next decade under a new public-private model.

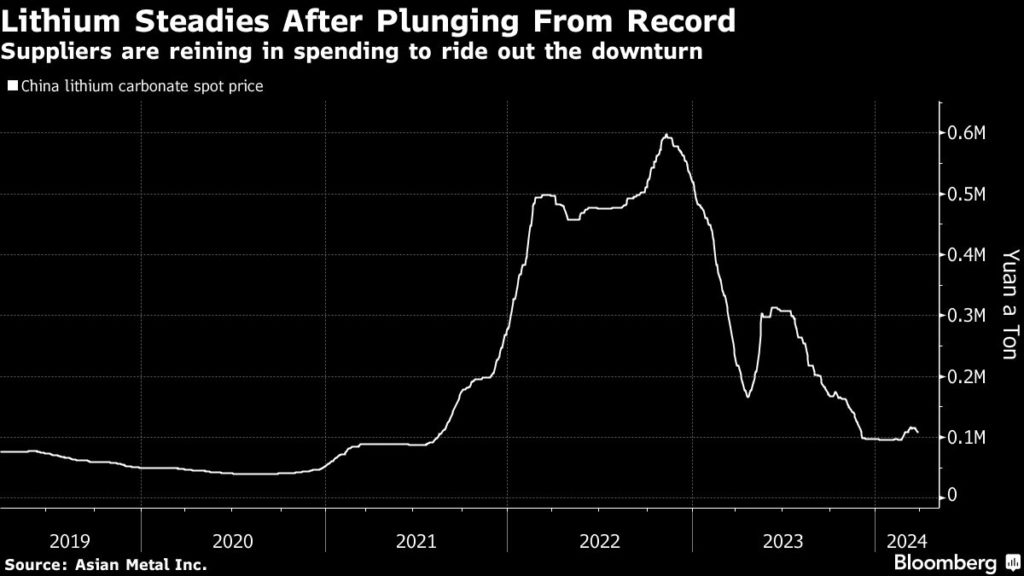

If Chile can pull it off, the flood of new supply would be cheered by the EV supply chain as demand grows in the move away from fossil fuels. Lithium remains a highly volatile and still immature market. Prices surged through late 2022 as battery makers stocked up amid accelerating EV sales before plunging last year as buyers ran down inventories.

Two thirds of additional production out of Chile would come from SQM’s planned partnership with state-owned Codelco, and the other third from new projects, Marcel said. The target doesn’t include proposed expansions at Albemarle Corp.’s operations.

President Gabriel Boric’s plan to tap more of the world’s largest reserves — putting an end to years of market share loss due to strict output quotas — is divided up into three categories.

Two salt flats are considered strategic, meaning future contracts will be controlled by the state. In two others, state-owned companies will have the flexibility to negotiate terms with private partners. In a third process, contracts for as many as 26 other areas will be put out to tender.

The government expects three or four new projects to be under development by 2026, including the Codelco-led Maricunga venture, one other area currently under the domain of a state company and a couple of private operations, Marcel said. Another mine on the giant Salar de Atacama “would be difficult” given water limits, he said.

When Boric first unveiled his lithium strategy a year ago, industry concern centered on his emphasis on a larger role for the state and the need to move to new methods that promise to make extraction more efficient and greener but are barely used commercially anywhere in the world.

This week’s announcement confirms that, at least in some areas, the door is open for companies to control projects and even go it alone. In addition, new production methods – collectively known as direct lithium extraction – will be a “desirable variable” rather than a requirement in new contracts, Marcel said.

“Many of the interpretations assumed that this was a more statist policy than it really is, perhaps because of political bias,” the minister said. “The important thing is that now the situation has been clearly clarified.”

(By James Attwood and Matthew Malinowski)

Comments