Blade runners: how LFP batteries brought EV metal markets back to earth

In February 2020, your reporter published the following headline:

Tesla’s China surprise big blow for cobalt, nickel price bulls

In a surprise move, China’s top battery manufacturer CATL will supply Tesla with lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries for Model 3 production at its newly built $2 billion factory outside Shanghai.

A follow up a year later confirmed the blow was bigly:

Cobalt, nickel free electric car batteries are a runaway success

Few months in, LFP Model 3 already commands 5% of global EV market, counts for 21% of Tesla battery capacity hitting roads–even before key patent expiry next year.

The iron fist

It’s January 2024, and unfortunately for said cobalt and nickel bulls the blow from the iron fist is even more severe than feared. And the runaway success has become a battery-powered juggernaut.

During that month nearly four years ago when Elon Musk first announced the move to LFP batteries, the cathode chemistry contributed less than 50 tonnes to overall battery metal demand, according to Adamas Intelligence, Toronto-based research consultants tracking demand for EV batteries by chemistry, cell supplier and capacity in over 110 countries.

The 50 tonnes LFP batteries used were a fraction of the nearly 13,000 tonnes of lithium, graphite, nickel, manganese and cobalt that found their way into the batteries of electric passenger cars sold during February 2020.

NCM (nickel-cobalt-manganese) and Tesla-Panasonic’s NCA (nickel-cobalt-aluminum) dominated the market for electric cars at the time. LFP fares badly against ternary cathode batteries in terms of energy and power density and therefore charging time and range. LFP’s cold weather performance is also significantly worse, but is hard to beat when it comes to cost, is better at thermal stability not catching fire and lifespan.

Musk had long voiced concerns about nickel supply – once saying that he called up all the big mining CEOs to ask them to please make (sic) more nickel. Thrifting out cobalt was also a priority at the Texas-based electric car pioneer with Musk saying publicly that Teslas were virtually cobalt-free while simultaneously inking offtakes with Glencore.

At the time, LFP was associated with tiny and tinny city runabouts like the Wuling Hongguang Mini EV Macaron (not making that up and yes, there is a cabrio version and it’s called the FreZe Froggy in Europe), end-mile delivery vans, buses and other special purpose vehicles.

Range then as now was a top concern for those looking to electrify and the Wuling Mini EV (a GM joint venture creation now available in the top-of-the-range Gameboy Edition; look it up) only managed around 100 miles in lab conditions.

The Mini EV surpassed the Tesla Model 3 as China’s bestselling EV in 2020. A sticker price of less than $6,000 clinched it.

Like other outlets, this one was skeptical of the idea that LFP fitted well with Tesla’s luxury and sporty carmaker image.

We were wrong. Sorry again Mr Musk.

Build your nickel, cobalt free dreams

Weeks after Tesla’s Shanghai surprise, LFP received what turned out to be an even bigger boost to its build out.

In March 2020, BYD “unsheathed to safeguard the world” its Blade batteries. The Shenzhen-based auto and battery manufacturer’s breakthrough technology compensated for the inherent energy density limitations of LFP by cramming more cells into battery packs.

BYD even said at the event (online only – this was March 2020 after all) it was happy to share the technology with all interested parties. Much was made of the safety of LFP over NCM. BYD shifted its entire range to LFP.

The month of the unsheathing Tesla supplied new owners of its S,3,X models and just launched Y, nine power hours for every one BYD did.

Today BYD’s full electric range outsells Tesla in good months. Factor in its popular plug-ins – also LFP only – and BYD is nearly 600,000 car lengths ahead of Tesla. Tellingly, BYD started out as a battery company in the 1990s.

BYD, in which Warren Buffet famously bought a stake in 2008 for $232 million that is still worth some $6 billion after years of steady divestment, sells one out of every five EVs around the world. That’s despite being largely absent from markets outside China (BYD supplies Tesla’s Berlin factory with LFP batteries).

LFP now also runs the gamut of vehicle segments. All the way from the Wuling Hongguang Nano EV (for those who found the Mini a bit too bulky) to BYD’s gigantic YangWang U8. The YangWang wagon can do a 360 degree tank turn, float on water and sail at 1.62 knots and retails for $150,000, making it China’s most expensive EV. It also weighs 3-and-half tonnes (another comparative downside of LFP).

The cheaper of the pack

During the first ten months of 2023 LFP cornered 31% of the global EV battery market in GWh terms despite virtually zero LFP manufacturing capacity outside China. By the time final registrations for the calendar year are tallied, it may well be a third.

Nickel and cobalt containing batteries are now cut out of over half the Chinese market in GWh terms. With China leading the pack, on a cumulative basis LFP recently overtook NCM 523 (roughly 50% Ni, 20% Co, 30% Mn) as the top cathode technology in the global EV parc. Adamas battery capacity data is based on vehicles delivered to end-customers, not wholesale markets or sales to dealerships.

LFP is now also firmly in the driver seat at Tesla. The vast majority of newly sold Model 3s around the world this year have been LFP powered. And the LFP-version of the Model Y occupies the top spot in China in terms of battery capacity deployed.

The cost advantage of LFP shrank considerably as lithium flirted with $80,000 a tonne in 2022, but the decline has been swift since then. In China, spot prices for lithium carbonate are below $16,000 a tonne, hydroxide used in hi-nickel batteries dipped below $15,000 last week and spodumene averaged $1,300 a tonne – all down by 80% in 2023 with losses accelerating into the new year, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

The bounce caused by the trucker strike in central Africa and worries about DRC elections have turned into a dead cat and cobalt enters 2024 below $30,000 a tonne.

Coupled with the chaotic highs on London nickel markets giving way to a steady decline to the mid $16,000s a tonne on the LME, lithium’s losses have turned LFP cheap and cheerful again.

Thanks a tonne

The 50 tonnes of LFP induced demand of February 2020 is now 27,000 tonnes per month, to which you can add another few 100 tonnes from best of both worlds LFP-NCM combo batteries finding their way into more and more EVs.

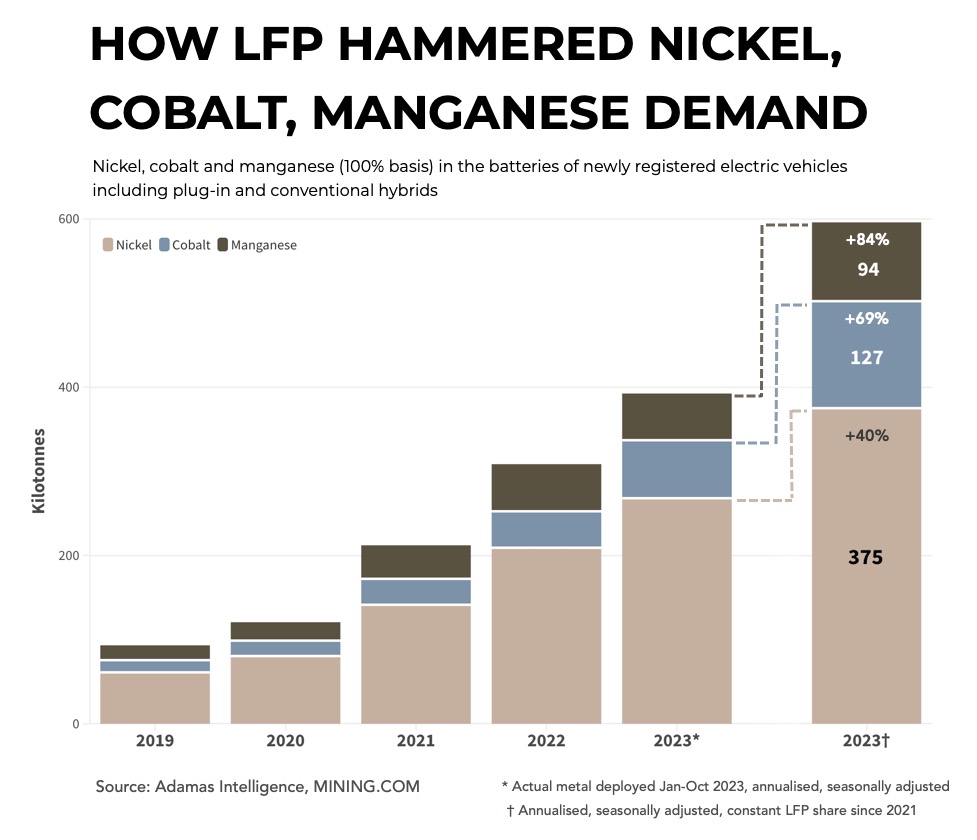

From just over 33% in 2019 before LFP’s coming out year, nickel’s share of global active battery material demand has now fallen below 25%. From a nicely carved niche of 8% in 2019, cobalt clings on at less than 5% now. Manganese is down from close to 9% to 6%.

Nickel’s waning battery metal share comes despite the rapid adoption of nickel rich chemistries for NCM batteries. In early versions of NCM the metals were applied in a roughly 1:1:1 ratio. In 2023 this mix makes up 1% and that’s probably dealerships moving stock forgotten on a lot somewhere.

So far this year NCM 811 with nickel in excess of 80% has cornered more than a fifth of the market in GWh terms, surpassing NCM 523 (roughly 50%+ nickel), according to Adamas. Tesla-Panasonic’s third generation NCA also contains over 80% nickel while NCM cathode chemistries with 90% nickel have been available for a while.

Since lithium carbonate equivalent tonnages and LCE prices are almost always quoted in industry literature it’s easy to forget that tonne for tonne nickel is in fact THE battery metal and on a 100% metal content basis total demand for cobalt and manganese is not that far behind lithium. (New Year’s resolution: Always divide by 5.323.)

Or in the words of Musk in 2016 well before LFP: “Technically, our cells should be called nickel-graphite, because the primary constituent in the cell as a whole is nickel. There’s a little bit of lithium in there, but it’s like the salt on the salad.”

Blade runners

So what would a world look like without blade runners like BYD’s Dolphin, Seal, Han, Song and YangWang and Fangchengbao luxury and off-road brands? What if Tesla opted to employ NCM and NCA for all their vehicles? Or if the LFP cells supplied by CATL – the world’s biggest EV battery maker by a country mile – did not displace a third of its NCM output?

Hold onto your hard hats. It’s not pretty.

The combined battery capacity of EVs (including conventional and mild hybrids) is likely to surpass 700 GWh in 2023, a 45% gain over 2022 and is more than five times the size it was in 2020 and the basket of battery metals in newly sold EVs should easily surpass one million tonnes, Adamas predicts.

On an annual basis potential nickel tonnes lost this year is likely to top 107,000 tonnes. For cobalt, the metal that went unwanted because of LFP would be more than 38,000 tonnes or roughly 20% of global production last year. Producers of manganese for the battery supply chain would have enjoyed 58,000 tonnes greater annual demand.

Add tonnes lost to LFP to actual use for the year, and you get to 94,000 tonnes of cobalt demand from the EV sector. That’s more than half of cobalt mined each year ending up in the EV industry. For nickel that number is 375,000 tonnes and manganese 127,000 tonnes.

Adamas crunched the numbers on the basis of mid-market NCM 5-Series being the battery doing the work of LFP, not NCM 811. Under the latter scenario the what-could’ve-been for nickel miners would naturally be even more eye-watering.

Also keep in mind the kilograms that end up in every EV are fractions of what would have been procured upstream.

A factor that is sometimes omitted from estimates of metal requirements is low yields in the conversion and manufacturing process.

CATL disclosed 50% yield in its factories early on, exacerbated by ramp up challenges, but even at a steady state your average cell producer turns as much as 30% of the metals entering factory gates into black mass. Between the mine mouth and the gigafactory many more tonnes are never recovered.

Battery bulge

Despite the havoc wreaked by LFP, other trends are nickel and cobalt’s friends. The combined battery capacity of EVs sold last year surged by 45% year on year and is running well ahead of new registrations which are up 33% globally, according to Adamas data.

Battery capacity is a better gauge of metal demand than unit sales alone and not only are packs bulking up, the shift to high-nickel batteries has some way to go.

Last year, the sales weighted average full electric vehicle – including LFP-powered units – sold globally contained just under 25 kilograms of nickel in its battery, 7% more than in 2022. The average battery in plug-in hybrids, which are soaring in popularity, particularly in China, had 6.4kg of the devil’s copper, a 12% year on year jump.

The big battery bulge is also keeping cobalt weightings from falling more quickly amid ongoing thrifting. On average full electric cars sold globally in 2023 contained 4.8 kilograms and plug-in hybrids 2.2 kg up 5% and 2%.

Nickel’s not classy

It’s perhaps too easy to blame LFP for today’s Ni-Co situation although it was earlier predictions for spectacular demand growth from electric cars that spurred much of the investment in new supply and in the case of nickel, new industrial processes, in the first place.

Global nickel exploration (and by extension cobalt) budgets, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence are up 19% last year to a remarkable $732 million, nearly a quarter of what is being spent expanding or finding new copper resources. Nickel only reached annual output of 3 million tonnes last year and that’s after years of robust growth – the copper industry is nearly eight times the size.

Most of the nickel mined around the world still ends up as stainless steel and soft demand from the construction and manufacturing sector on the all-important Chinese market has seen vast surpluses in non-class 1 nickel – not suitable for the battery supply chain – build up.

However, when it comes to demand from the EV sector, nickel class matters less today. Large chunks of the China-Indonesia nickel-pig-iron industry are pivoting towards LME and battery -friendly products (not so environmentally friendly though).

A rapid ramp up in Indonesia nickel mining, thanks to a slew of new high-pressure-acid-leach (HPAL) projects (even attracting investment from as far afield as Dearborn) which are about as environmentally conscious as they sound, only adds to the weak fundamentals. Indonesia is already responsible for half of global nickel output and Chinese investment in the archipelago is not slowing.

Cobalt blues

Cobalt probably had most to gain from the EV revolution. It’s a small highly concentrated market, with few big players and sparkling per tonne prices.

Indeed, Glencore was the first major to herald a new dawn for mining thanks to electric cars, telling investors in 2017 that “as early as 2020, when electric vehicles would still make up only 2% of new vehicle sales, related metal demand already becomes significant.”

That prediction proved conservative – global penetration reached over 5% in 2020.

But cobalt thrifting had become more of a priority after the 2018 spike to above $100,000 tonne scared automakers and ESG-transgression hunters went looking for breaches in the Congo.

Nearly all cobalt supply is a byproduct of nickel and copper mining. As far back as 2019, BMW’s offtakers pounced on what is the only primary cobalt mine in the world. Jervois halted construction on its Idaho project March last year, but Canada’s Fortune Minerals may provide an opportunity for enterprising automakers.

In an irony that would not be lost on cobalt promotors, rumours are swirling that Glencore is considering suspending production at Mutanda again to shore up cobalt prices (as it is, Mutanda’s output is down 15% due to lower grades).

It worked in 2019 when Mutanda still had 20% of the market, but new supply not just from the Congo but also Indonesia where laterites come with a thick layer of cobalt would mute the impact this time around.

Cobalt just does not have much going for it at the moment. Vast cobalt stockpiles from Tenke Fungurume in the DRC are still being sold downstream and the copper-cobalt mine’s Chinese owner’s expansion plans are well under way. Tenke could soon rival Mutanda as the world’s largest cobalt mine and CMOC overtook Glencore as the world’s number one cobalt producer in 2023.

A new railway through Zambia to Tanzania’s Dar es Salaam port will also alleviate cobalt’s lasting logistics problems, which have underpinned prices in the past.

EVs overtook all else when it comes to cobalt demand a few years ago now, so a fall-off at the margins coupled with the small size of the market can quickly and thoroughly depress prices.

Manganese meh

Manganese is often overlooked in the battery metals space and the excitement stirred by Volkswagen’s newly-formed PowerCo battery subsidiary back in March 2021 has long dissipated. At the time, the world’s no 2 carmaker said it’s building six new plants and is looking at high-manganese batteries for its mid-range vehicles.

But last month Volkswagen said a fourth European battery factory is postponed indefinitely, much to the relief of Czech taxpayers who unlike their Canadian counterparts now won’t have to shoulder billions in subsidies and tax breaks for the honour of having a large battery factory.

Tesla has also expressed interest in manganese, with Musk saying last year high-manganese batteries could be an alternative to LFP, but there’s been little news since then.

Besides, with ore production of 20 million tonnes per year, LMFP and other high-manganese chemistries were never going to light a fire under manganese at the mining level.

That said, downstream battery ready compounds do become scarce from time to time and manganese sulfate in China has not succumbed the way lithium, cobalt and nickel have. Manganese sulphate is down 29% over the last year, changing hands for less than $700 a tonne in China.

US, EU 2. Affordable Chinese EVs 0

Other development that could keep the LFP wolf from the door on markets outside China a bit longer are geopolitics and a growing mercantilist approach to trade in the world’s largest economies.

While Chinese-made EVs have close to zero presence in the US, Europeans can and often do choose Geometry, HiPhi, Lynk & Co, Ruixing, Seres, Aeolus, Zeekr, XPeng, Weltmeister (one of China’s earliest EV startups ribbing Wolfsburg and co), and others over homegrown automakers like Volkswagen, Peugeot and Fiat.

Get behind the wheel of a Tesla, Citroen, BMW, Dacia, Honda, Renault or Smart and there’s also a good chance you’re driving a made-in-China vehicle. Last year in terms of battery capacity rolled onto roads, nearly a fifth of the EVs bought by Europeans were made in China.

The EU’s probe of Beijing’s subsidies to its EV industry is all but inevitable to result in tariffs and other measure to limit access to EU car markets while in the US, long-awaited new rules on so-called foreign entities of concern (FEOC) all but eliminates direct Chinese involvement.

In 2024 EVs that contain any battery components manufactured or assembled by China will not be eligible for the US federal tax credit, currently a maximum of $7,500 per vehicle. The incentive cut-off date for any lithium, nickel, cobalt and graphite or other battery metals produced by, or which make their way through China, is 2025. Rare earths used in nearly 90% of all EV motors are already subject to IRA rules.

Not much more than a handful of electric cars sold in the US would qualify. On top of that a bipartisan group of lawmakers also recently asked for Trump era duties of 25% on Chinese automobiles to be doubled and to close any loopholes should China locate factories in Mexico, for instance.

The new guidelines may allow US automakers to cut licensing and technology deals with Chinese companies. This should give a green light (although that’s far from clear) to ventures like Ford’s partnership with CATL for its LFP plant in Michigan, and Tesla’s venture in Texas with the Chinese behemoth.

Ford made much of the fact that BlueOval – which is now going to be 40% smaller than originally envisaged – would produce LFP batteries, calling it a “key part” of its US EV plans allowing it to “scale more quickly, making EVs more accessible and affordable for customers.” Given the success of Tesla and BYD with LFP, US automakers are bound to follow in their tracks.

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence sees LFP factory growth outside China at factors more than NCM build-out. But that would not nearly be enough for the rest of the world to embrace the technology at the same speed and scale as China, which itself is expected to grow LFP cathode capacity by more than three times by the end of the decade, according to the London-headquartered research firm and pricing agency.

FEOC FOMO

The new EV provisions pitted automakers against mining firms with the former arguing that barring China from directly participating in the US mine-to-megawatt supply chain would be close to impossible given the short timelines and would delay EV adoption by Americans by pushing up costs.

The FEOC rules are intended to complement the Inflation Reduction Act’s requirement that any EV subsidy is conditional on a percentage of all material inputs being sourced either domestically or from a US free trade partner. Currently the threshold is 30% and will rise to 80% in 2027.

An exception was made for foreign subsidiaries of privately-owned Chinese companies in friendly countries, like Australia and Indonesia, but even these entities may fall afoul of the rules if they are deemed to be under the control of the Chinese government. Even off-take agreements with Chinese buyers – and for EVs they act as close to a monopsony – may be deemed to bring too much CCP influence to bear.

Miners, justifiably, want rules that speed up and incentivize domestic production, not least because the time from resource discovery to mine production is often counted in decades. The convoluted US permitting system also provides almost zero certainty that investments in new mines will pay off – no matter to what extent miners dot environmental i’s and cross social license to operate t’s.

The one-two punch by US and European authorities may end up bringing the much talked about – and yearned for – premium pricing for metals and minerals supplied by Western firms. What it won’t do is make EVs cheaper or reignite sales growth in these markets.

The road not travelled

While nickel-rich EV batteries will always have a large niche, it’s difficult to shake a sense of what could’ve been:

The latest and greatest Model Y – the global bestselling EV on a GWh basis – coming out of Tesla’s Texas factory has a NCM 811 battery which uses kilograms of cobalt that approach double digits and more than 50kg of nickel. The Cybertruck uses NCA for now, but the bestselling truck in the US, the Rivian R1T is moving to LFP so that the California startup can stop making up in volume what they lose per sale.

Imagine selling 20 million a year – as Musk promised – of these workhorses. Instead, the unwanted tonnes of Ni-Co-Mn will only pile higher and higher. Or stay buried.

According to China’s automobile association, November was the first one million month for electric car sales and December is likely to top that. The US market is expanding by more than 50% year on year and penetration rates are still in single digits.

Germany is betting its industrial future, if not its national pride, on the ability to catch up to China in the electric car business. But at the moment three gasoline powered cars leave autohaus lots for each with a charging cable in the frunk.

South Korea is the world’s sixth largest EV market in terms of battery power rolling onto roads in 2023 and the only country that rivals China in battery output despite the absence of LFP capacity. Yet EV penetration is 11% south of the DMZ. As for Japan, its power hours fall short of Belgium’s.

How much of China’s lead can be ascribed to LFP remains up for discussion considering all the moving parts in the EV supply chain. But it’s safe to say China would not have been able to deploy more battery power in electric cars last year than the next 50 countries combined if it hadn’t.

Sodium on the podium

Vehicle electrification is the biggest thing to happen to the automotive and mining industries in a century. The green energy transition more broadly is allowing mining to step outside the shadow of oil and gas.

Crucially, for the first time metal extraction aligns with the goals of the environmental movement (even though the message does not seem to be getting through).

But the story of how LFP crashed into battery metals illuminates something else about mining.

Apart from gold which is money, the arrival of EVs has exposed the industry to the vagaries of technological change like never before.

LFP has severely dented nickel and cobalt prospects and after all metal pricing is all about the marginal tonnes. The next thing to come out of a lab could turn the mine that took decades to build into a white elephant. Substitution has and will keep miners awake at night.

Can sodium-ion batteries do to lithium-ion what iron phosphate did to nickel and cobalt?

BYD broke ground on its first $1.3 billion sodium-ion battery plant just today. Three former Tesla executives have set up a sodium-ion company and the first sodium-ion EVs could go on sale soon and sodium could also salt the field of stationary energy storage.

Until now graphite has been immune to changing chemistries, but the hard carbon anode used for sodium-ion cells can be made from food scraps. Can solid state lithium batteries, which can also do away with graphite for the anode, nix the parts sodium doesn’t?

Crude awakening

Unlike in mining, oil and gas demand destruction is not an intrinsic part of technological progress – at least not one that can play out over a few short years like cobalt and nickel free cells. As the outcome of COP28 showed, it must be imposed.

Indonesia, Russia and the Philippines control some three-quarters of global nickel supply, 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from the Congo and additional tonnes will mostly come from Indonesia.

If copper – ground zero for the energy transition – was crude and output could be turned up or down after a secretariate meeting in Vienna, Chile would be Saudi Arabia and all the Gulf states combined. It would be Peru’s sovereign wealth fund dangling $1 billion in front of a French soccer player.

But as platinum group metal watchers must realise by now, establishing an Opec+ style cartel will forever be a pipe dream in mining.

Nickel is not the new gold and no, lithium is not the new oil.

Yet here we are.

Back at the salt mines.

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

2 Comments

Richard

The article is too long, rambling and leaves me confused as to what it is trying to say.

Frik Els

Hi Richard. TL;DR: LFP batteries had a big impact on nickel and cobalt demand from the EV sector within a short period of time showing the risks posed by rapid technological change on mining industry economics, particularly given the mismatch between mine development timelines and changes in metal demand.