The US extended its claims on the ocean floor by an area twice the size of California, securing rights to potentially resource-rich seabeds at a time when Washington is ramping up efforts to safeguard supplies of minerals key to future technologies.

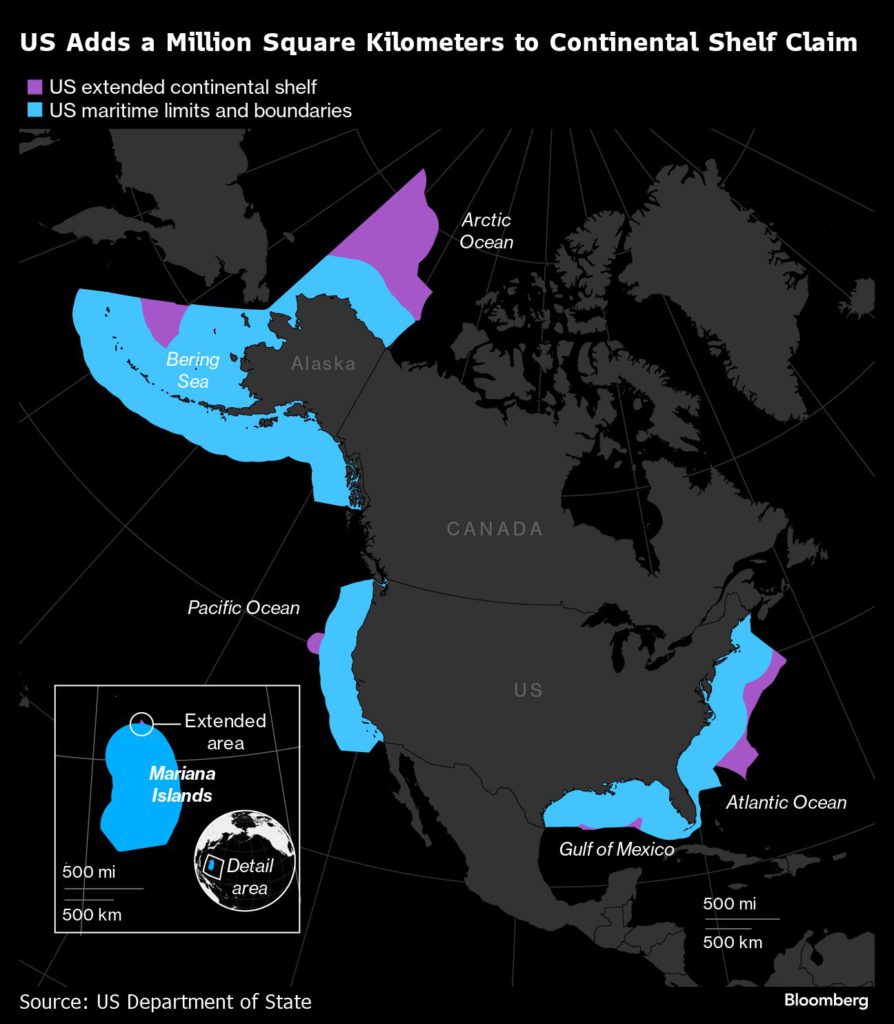

The so-called Extended Continental Shelf covers about 1 million square kilometers (386,100 square miles), predominantly in the Arctic and Bering Sea, an area of increasing strategic importance where Canada and Russia also have claims. The US has also declared the shelf’s boundaries in the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf of Mexico.

The long-awaited announcement earlier this week maps the outer reaches of the US continental shelf, the country’s land territory under the sea. Under international law, countries have economic rights to natural resources on, and under, the seabed floor based on the boundaries of their continental shelves.

“It’s a huge deal because it’s a huge amount of territory,” said Rebecca Pincus, director of the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, which has devoted an entire web page to the ramifications of this week’s news. “It’s US sovereignty over the seabed floor, and so whether it’s seabed mining, or oil and gas leasing, or cables, or what have you, the US is announcing the borders of its ECS and will have sovereignty over those decisions.”

The US State Department said that the development “is about geography, not resources.”

The US, like all countries, has “an inherent interest in knowing, and declaring to others, the extent of its ECS and thus where it is entitled to exercise sovereign rights” it said in an emailed response to questions. Continued mapping and exploration will be needed to understand the areas’ habitats, ecosystems, biodiversity and resources, it added.

While it’s unclear what materials, if any, can be exploited, the claims come as Washington seeks to boost access to so-called critical minerals that are necessary for electric vehicle batteries and renewable energy projects, industries the Biden administration has tagged as key national security concerns. Meanwhile, there are competing calls to protect the fragile Arctic environment — the fastest warming part of the planet — as climate change opens up the region to potential development.

The US continental shelf contains 50 hard minerals, including lithium and tellurium, and 16 rare earth elements, James Kraska, chair and professor of International Maritime Law at the US Naval War College, wrote in an article this week. The extension “highlights American strategic interests in securing these hard minerals on its seabed and subsoil, lying sometimes hundreds of miles offshore,” he wrote.

The most recent assessment by the US Geological Survey, conducted in 2008, estimated that about 90 billion barrels of undiscovered oil and 1,670 trillion cubic feet of gas lie inside the Arctic Circle, along with critical metals needed for electrification. However, most of that estimate is based on land studies and the offshore potential is largely unexplored.

More than half of America’s extended continental shelf — 520,400 square kilometers — stretches in a large wedge north of Alaska toward the Arctic Ocean, including an area that overlaps with Canadian claims to the seabed floor, according to the US statement.

Another 176,300 square kilometers lies in the Bering Sea, between Alaska and Russia, but falls on the US side of the maritime boundary between the two countries. Canada and the US don’t have a maritime boundary agreement in the Arctic and establishing the US outer limits in the Arctic “will depend on delimitation with Canada,” the State Department said in its executive summary.

Canada’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which the US never ratified, governs maritime zones around countries. Under the law, countries have the right to any resources in the sea or seabed floor within their so-called exclusive economic zones, which can stretch up to 200 nautical miles off the coast.

But beyond that, they can claim economic rights to resources on or below the seabed floor where their continental shelf extends, although not within the water column. The seas above also remain international waters. Russia, Denmark and Canada have waited years for their overlapping Arctic seabed claims to be reviewed by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, a UN supported group, with Russia the first to receive a ruling earlier this year.

The State Department said in its response to questions that the US would need to establish maritime boundaries in the future with Canada, the Bahamas and Japan where their claims overlap. It added that the US uses the same rules to determine its extended continental shelf as in UNCLOS, which it said the Biden administration supports joining.

The decision to unilaterally delineate its continental shelf boundary, rather than to ratify UNCLOS and then submit a claim through the commission, may raise the ire of other countries, said Pincus at the Wilson Center.

“I think a lot of other countries around the world are going to have thoughts about how the US has done this,” she said. It also may reduce the likelihood of the US ever ratifying the law since a major reason for doing so would have been to make a CLCS claim, she said.

(By Danielle Bochove)

Comments

Mark Rose

That map claims areas that Canada also claims. Canada has a maritime boundary dispute at both “ends” of Alaska.