China is in the midst of a breakneck expansion of its copper industry that’s reshaping global flows of the essential metal for the world’s energy transition.

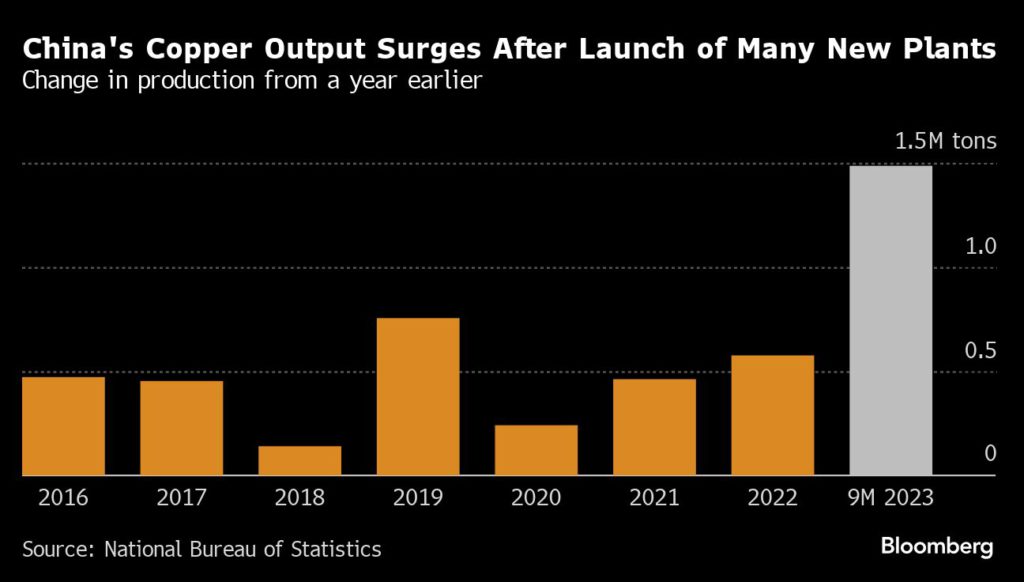

The Asian nation’s grip on the supply of other green metals like lithium, cobalt and nickel, used in electric vehicle batteries, has already prompted worried Western governments to encourage separate supply chains. Meanwhile, China’s production of refined copper — and its share of world output — is heading for a record this year after a burst in construction of new smelters.

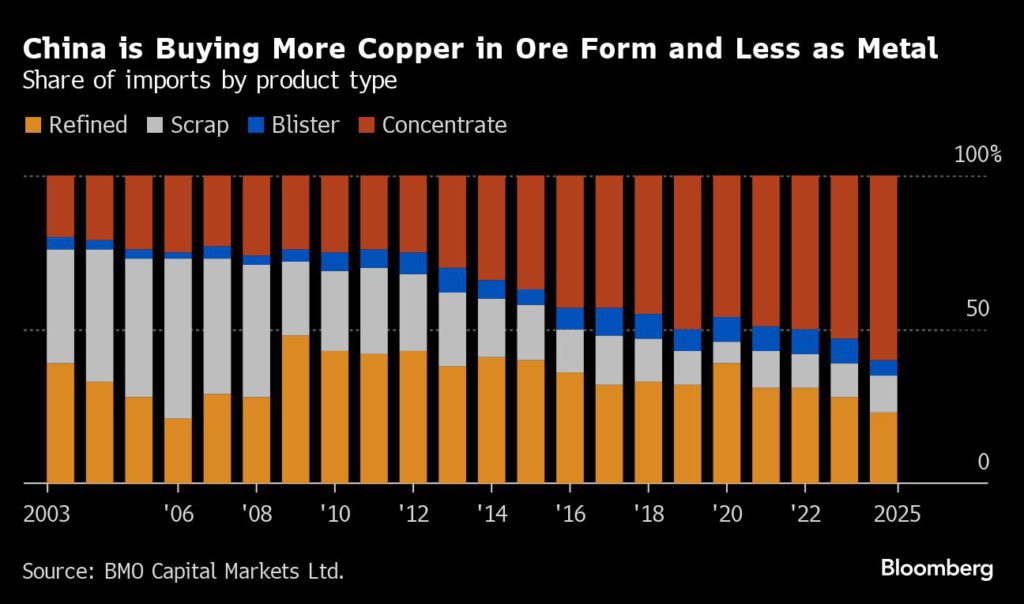

The rapid ramp-up in capacity brings a fresh dynamic to a market that for 20 years has been driven in large part by how much buyers in China are willing to pay. The country will still import growing amounts of copper, but more as ore rather than refined metal.

Copper has been labeled the most important commodity in the age of decarbonization for its use in everything from EVs to wind turbines and vastly expanded power grids. Booming Chinese demand from green technologies has been a bright spot for an otherwise beleaguered world metals market in 2023.

“Like all countries, China sees a strategic need for copper — particularly now with the growth in green energy applications — and China like other countries wants to ensure self sufficiency,” said Craig Lang, principal analyst at researcher CRU Group. China will account for about 45% of global refined copper output this year, according to CRU.

The smelter build-up will be a key talking point for hundreds of copper-industry executives descending this week on China’s commodity hub of Shanghai for Asia Copper Week. Miners and smelters will negotiate key annual ore-supply contracts, and attendees will take the latest temperature of Chinese demand.

Despite the financial toll of the pandemic and China’s property crisis, the nation’s metals consumption has been relatively strong in 2023. That has probably helped copper stave off an even deeper market slump, with prices only slightly lower than this time last year.

CRU sees copper demand in China growing 5% this year, while Goldman Sachs Group Inc. named copper as one of its top commodities picks for next year on a “robust green demand environment” — especially in the Asian powerhouse.

“We expect to find Chinese players slightly less cautious than may have been feared two months ago,” Colin Hamilton, managing director for commodities research at BMO Capital Markets Ltd., wrote in a note ahead of the Shanghai gathering.

The expansion of smelting capacity echoes the history of China’s other metals industries. Until 2006, the country was a net importer of steel, for example. But a wave of new capacity eventually led to a flood of exports — hurting international steelmakers and fueling global trade tensions in the pre-Trump era.

China’s copper smelting capacity will increase by another 45% by 2027, accounting for 61% of expected new plants around the world in that period, according to Carlos Risopatron, director of economics at the International Copper Study Group.

Simon Hunt, a 50-year veteran of the copper industry who now runs his own consultancy, reckons China could turn net exporter of copper by 2025 or 2026 as production booms. That’s not a consensus view, but the viability of exports is a topic of discussion in the industry.

In any case, China’s copper smelters could pile pressure on their global peers in coming years as they “pay up” to get the feedstock they need, Hunt said. The closure of older smelters in the rest of the world could be the outcome.

For now, the rapid expansion of copper smelting capacity is triggering a race to secure copper concentrate to feed the smelters, with annual contract negotiations taking place this week against the backdrop of a tightening market for the raw material.

The treatment charges that miners pay smelters to process ore drops when concentrate is scarce. That dynamic is likely to be reflected in a fall in fees for next year to $84 a ton from $88, according to an estimate from Shanghai Metals Market.

“Global copper concentrate supply will be loose in the first half before switching to a deficit in the second,” said Mysteel analyst Meng Wenwen, who also expects a decline in fees.

At the same time, the increase in smelting is making China less dependent on imported copper metal, leading to expectations of an oversupply of the refined form that sets the price on the London Metal Exchange, the world’s benchmark.

That’s causing headaches for China’s traditional suppliers, like Chile, and has forced the world’s biggest copper producer Codelco to slash the annual premium it charges to Chinese buyers.

To be sure, China isn’t the only nation building new smelters. India, Indonesia and Africa’s copper belt are also adding capacity. And China is mulling caps on smelter expansions for environmental reasons, although restrictions are unlikely to be imminent.

The Shanghai copper event comes at a time of heightened uncertainty for global growth, with major economies still at risk of recession and investors unsure whether the Federal Reserve is done with rate hikes.

On Monday, copper ticked higher from its lowest close in more than two weeks, trading at $8,053 a ton by 10:28 a.m. Shanghai time. It’s down about 3.8% this year.

Although copper analysts broadly expect a slightly slower expansion in Chinese demand next year, China is still likely to outpace the rest of the world as Beijing continues to bolster the economy. Citigroup Inc. analysts including Wenyu Yao said a stable China should “give some support to commodities consumption and prices” next year.

“There are risks, like rising metal output, but demand concerns will be more focused around the rest of the world,” said Jiang Hang, head of trading at Yonggang Resources Co. in Shanghai. “For China, there aren’t too many worries.”

Comments