Two thousand metres down the mine shaft, you can see just as far as your headlamp shines, says photographer Louie Palu. It’s as hot as a scorching July day and the air smells like diesel. Your boots sink in the mud underfoot.

And when the shrieking drills quiet, you may hear the sound of cracking rock from elsewhere in the belly of the Earth. Miners call these unnerving noises “the bumps.” Some bumps are okay; some are not.

From 1991 to 2003, the Toronto-born photojournalist, now based in Washington, documented hard-rock mining operations in northeastern Ontario and northwestern Quebec.

Visiting more than 100 active, abandoned and closed mines in places such as Cobalt, Ont., and Val-d’Or, Que. – locales named for the metals pulled from the ground – Palu developed a holistic picture of mining that includes the work, the workplaces and the workers, as well as their communities.

The landmark series was collected in a pair of books created in collaboration with Charlie Angus (a writer and journalist before he became an MP). Some images appeared in The Globe and Mail, where Palu was once a staff photographer.

This fall, the Toronto Metropolitan University’s Image Centre revisits Palu’s seminal works of documentary photography with the exhibition Cage Call, including more than 50 photographs and a collection of ephemera from his time in the hard-rock mining belt.

It’s an exceedingly Canadian industry: Seventy-five per cent of the world’s mining companies are headquartered here, as art historian Siobhan Angus, Charlie’s daughter, notes in a supporting essay. But it’s a story rarely shown to Canadians.

“It’s this world that has been such a foundational part of our consumer culture,” Palu says, “but there are almost no photos of it.”

Just as Palu’s photojournalism has illuminated other hard-to-see topics, from asbestos exposure to the continuing militarization of the Arctic, Cage Call lends a human perspective to an immense industry that’s largely unseen.

”His profession drives him to really look for places where people can’t go themselves,” says exhibitions curator Gaëlle Morel. “He’s kind of the witness.”

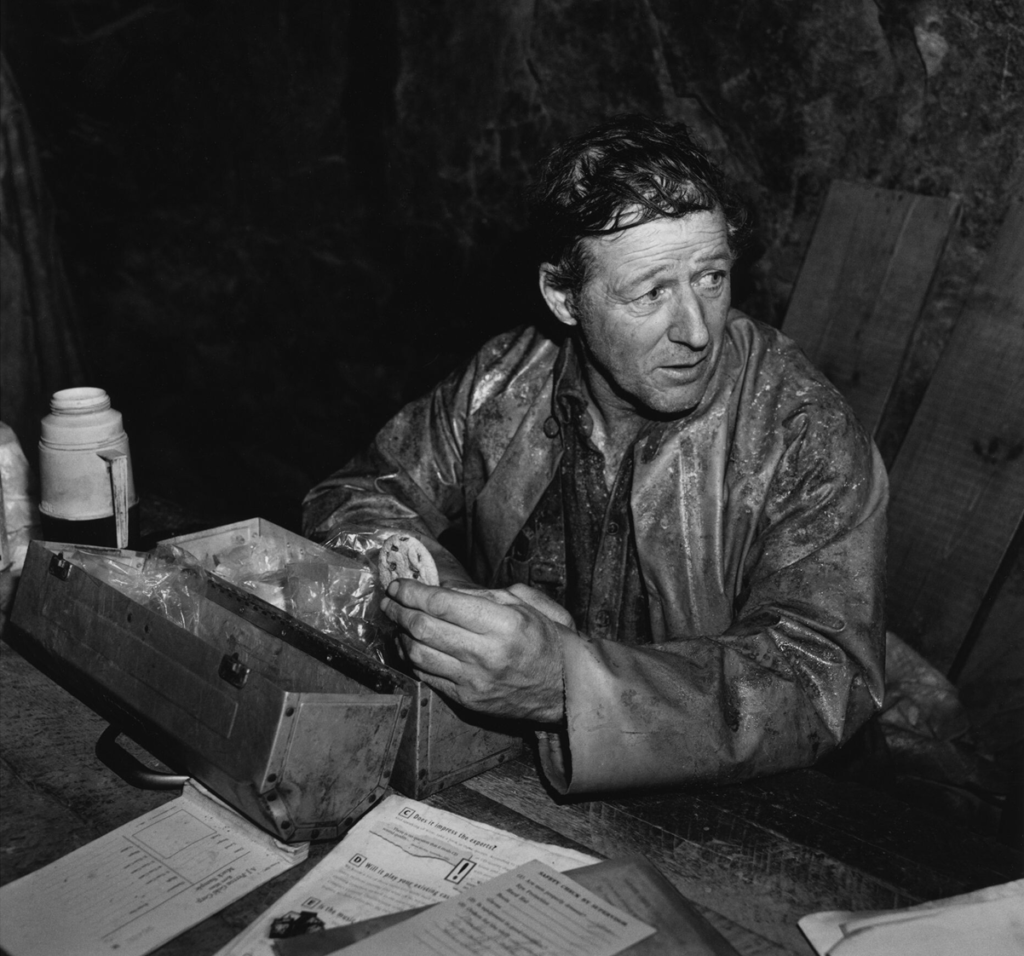

In dramatic black-and-white exposures, Palu presents sturdy figures armoured in oil slickers going to war on the rock face with spear-like jackleg drills. He pictures the Inco Superstack rising monumentally over a two-storey family home in Sudbury, Ont. He shows what lunch looks like 440 metres underground. He features bodies shaped by the dangerous, demanding work, and others – with burned or damaged or missing limbs – that have been reshaped by it.

“Bone and skin lose to rock and steel all the time,” Palu says.

In a newsprint supplement for the exhibition, which features some never-before-seen images the photographer calls his “hidden tracks,” Palu includes a picture of seven older women, nicely dressed, from a social function at the Porcupine Dante Club in Timmins, Ont.

This is called “the widows’ table,” he explains. “How much more clear can it be that this is the type of job that, at least in the past, had this real life-and-death thing going on?”

A counterbalance to such deeply human stories, one gallery wall collects photographs from the subseries Industrial Cathedrals of the North. Here, Palu surveys the awesome architecture of a couple dozen headframes – the tall structure that supports a mine’s hoisting machinery – rising heavenward like church steeples. The images are arranged in a grid – like the typological studies of photographers Hilla and Bernd Becher, the curator points out – evincing the quasi-sacred aura of the boomtown edifice in one example after the next.

On the wall opposite, one of Palu’s most famous images appears as a small print. You must move close to read it. The photo shows a miner at 760 metres underground signalling for his equipment during the tunnelling or “sinking” of an elevator shaft. Arms outstretched beneath the curious opening, the figure looks as if he’s hailing a spaceship. “It’s a unique moment that you can only photograph once in a mine’s life,” Palu says.

Riding a big metal bucket down into the abyss, then standing there among the blasted rock, Palu says he felt as if he’d just landed on the moon himself. For the shaft miners, though, the task was utterly ordinary; it was just another shift. The image portrays that dissonance, and suggests most Canadians are alienated from the kinds of work their country is deeply invested in.

While Cage Call presents viewers with a compelling documentary of mining – in its many facets – around the turn of the 21st century, it also addresses the immediate present, bringing into focus the extraction of materials that are evermore crucial to our daily lives.

We rely increasingly on this work. The phone in your pocket uses dozens of mined metals and minerals from all over the world. Even Palu’s silver gelatin prints use the very metal some of them picture.

“Mining is photography and photography’s mining,” he’s fond of saying. “You can’t separate the materials from this beautiful vision we make.” Offering these peeks beneath the subterranean curtain, Palu wants the viewer to feel implicated. It is the mission of his work.

“Every day, there’s an illusion,” he says. “I think photojournalism could be something that shifts our consciousness.”

Comments