Trafigura Group is being sued by the billionaire Reuben brothers, as the fallout of a massive nickel fraud reverberates through global metal markets and ensnares some of the industry’s best-known figures.

Legal filings seen by Bloomberg News shed new light on the case that shocked the market earlier this year, when Trafigura said it expected to lose nearly $600 million in what it called a “systematic fraud” perpetrated by Indian businessman Prateek Gupta.

In them, Hyphen Trading Ltd., the company owned by the Reuben brothers which is bringing the legal proceedings, alleges that the fraud didn’t just involve thousands of tons of missing nickel, but also counterfeit shipping documents — which ended up being used to obtain financing from leading commodity bank ICBC Standard Bank Plc. It describes how containers supposedly holding nickel were shipped back and forth around the world, apparently to avoid having to open them and reveal their true contents.

Moreover, Hyphen accuses a Singapore freight forwarding company of being involved in Gupta’s alleged fraud. It also raises questions about Trafigura’s own actions, saying that the trading house stonewalled its requests to inspect its cargoes.

Spokespeople for Trafigura and for the Reubens declined to comment.

David and Simon Reuben are some of the best-known figures in the history of commodity trading, having made their first fortune in the take-no-prisoners world of 1990s Russia. Now worth a combined $14 billion, they have not been major players in metals trading for decades, focusing instead on building one of the world’s biggest real estate portfolios. But they have continued to dabble in the sector through entities like Hyphen, which describes itself as a “commodities trader and financier” focused on refined metals.

The allegation that fraudulent shipping receipts – known as bills of lading – have been circulating in the nickel market will add to concerns among traders and financiers of the metal, which has been hit by a series of recent crises. The documents are central to modern commodity trading: original bills of lading represent legal ownership of a cargo of commodities and are often bought and sold numerous times, as well as being used as collateral for borrowing before the goods are finally delivered to an end user.

The legal filings offer a detailed account of the inner workings of a commodity trade – the mountains of paperwork required to organize a physical shipment of metal around the world, followed by the shock and recrimination when things go wrong. It’s a tale as old as trade itself, and one that has played out repeatedly in recent years, as cargoes have been stolen, stuffed with worthless goods, or simply sold multiple times to different buyers.

The Reubens’ company, Hyphen, is in separate legal disputes with Trafigura over two different cargoes of nickel.

In one case, which is the subject of legal proceedings in Singapore, Hyphen bought just over $10 million of nickel from the London Metal Exchange and loaded it on to several ships – only to find that Trafigura’s lawyers had written to the shipping company claiming that the trading house was the rightful owner of the cargo instead.

Both Hyphen and Trafigura claim to have the original bills of lading – an impossibility that suggests at least one set of documents is counterfeit.

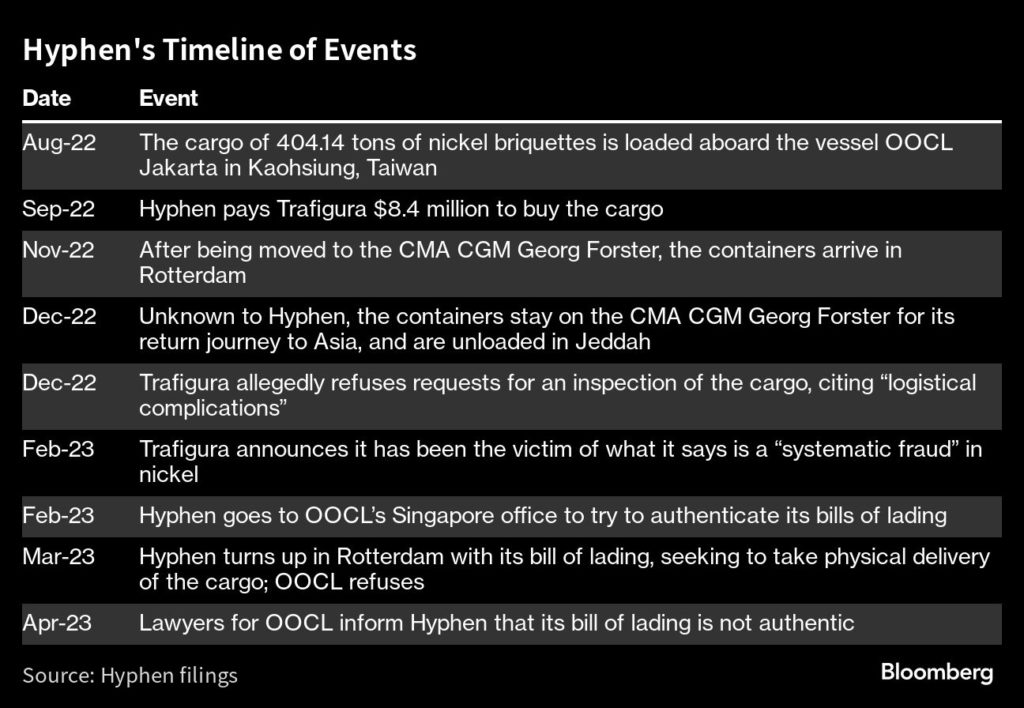

The other case, at the center of a UK High Court claim filed last week, focuses on a cargo of that Hyphen bought from Trafigura in September last year.

For $8.4 million, Hyphen bought just over 404 tons of nickel that had been loaded in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, onto a container ship called the OOCL Jakarta. The plan was for Hyphen to take delivery of the cargo when it arrived in Rotterdam. For a few months, it was financed via a repurchase agreement with ICBC Standard Bank. A spokesperson for ICBC Standard Bank declined to comment.

Things didn’t go so smoothly. While the containers did arrive in Rotterdam in mid-November — on a different ship — no-one told Hyphen. Instead, they inexplicably remained on the vessel when it set off on its return trip to Asia, before the “nickel” was finally unloaded in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, according to the complaint.

By December, Hyphen was still in the dark about the whereabouts of its cargo, and alarm bells were starting to ring. Together with Argentum, a US hedge fund it was working with, the trader began to press Trafigura for information.

“On 16 December, Hyphen asked for information concerning where the Goods had been stored at Kaohsiung (before shipment). Trafigura did not reply,” according to Hyphen’s complaint. “Hyphen pressed for a response on 19, 20, 22 December. Argentem itself pressed on 20, 21 and 22 December. Trafigura did not reply.”

Finally, on Dec. 27, Trafigura did respond to the demand for an inspection: according to Hyphen’s complaint, it allegedly refused the request, citing “logistical complications.”

By that point, unknown to the wider market, Trafigura was in full-blown crisis mode.

While Hyphen executives were becoming increasingly frustrated with Trafigura’s lack of answers about their cargo, Trafigura executives were in a similar state of agitation. Two months earlier, Citigroup Inc. suddenly informed the company it would no longer finance any trades with firms linked to Gupta. By December, Trafigura was applying “almost daily pressure” on Gupta for information, according to an earlier Trafigura court filing.

On Feb. 9, Trafigura publicly accused Gupta of fraud in a jaw-dropping announcement, saying it had spent more than half a billion dollars buying nickel from his companies only to discover when it opened the containers that there was no nickel inside. Gupta’s spokesperson has said he is planning a “robust response” to Trafigura’s allegations.

After that, Hyphen’s attempts to try and track down its cargo went into overdrive.

It visited the Singapore offices of the shipping line, OOCL, to present the original bills of lading it had received from Trafigura, in triplicate. But OOCL pointed out a discrepancy – while Hyphen’s bills of lading just listed Trafigura as shipper, the copy of the documents on OOCL’s system also included the name of a Singapore logistics company, Techies Logistics (S) Pte, as “forwarding agent.”

A month later, Hyphen tried a new tactic: it turned up in Rotterdam and demanded to take physical delivery of its cargo. OOCL refused. Finally, on April 5, OOCL’s lawyers finally delivered the bombshell: Hyphen had paid Trafigura $8.4 million and received a bill of lading that was not genuine.

“The Trafigura BL is likely to be a fraudulent document,” Hyphen concluded.

Since it went public in February, Trafigura has continually insisted that none of its employees were complicit in the alleged fraud.

And it acknowledged, in its lawsuit against Gupta, that it had sold cargoes bought from his companies to several third parties – including Hyphen – and was “potentially exposed to a claim by them in the event (which now of course seems likely) that those cargoes did not contain nickel.” It even raised the possibility that some of the bills of lading involved might not be genuine.

But Hyphen’s claim raises some uncomfortable questions for the trading house. It accuses Trafigura of preventing it from inspecting the cargo. And it further alleges that Trafigura was listed as the shipper on the bill of lading it delivered to Hyphen, meaning that the trading house had not just bought the goods from Gupta, but was the party responsible for delivering them to the shipping company.

Hyphen alleges that it was logistics company Techies that ordered the cargo to be sent back to Jeddah after it had already arrived in Rotterdam.

“Hyphen infers that Techies’ actions (whether known or unknown to Trafigura) were motivated by a complicity or other kind of involvement in the Gupta Fraud,” it said. Techies did not respond to emails, messages and phone calls seeking comment.

For Trafigura, the case represents yet another headache in the fallout from the alleged fraud. The company continues to pursue Gupta in court, and has made staffing and operational changes in response to the saga.

Hyphen, meanwhile, is seeking the $8.4 million it paid, plus costs and interest from Trafigura.

It still hasn’t been able to gain access to its “nickel.”

(By Jack Farchy, Alfred Cang and Joe Deaux, with assistance from Mark Burton and Archie Hunter)

Comments