Avoiding a climate catastrophe is often portrayed as a question of political willpower. Yet the shift to net-zero carbon emissions is also a daunting technical challenge. For one thing, retooling power systems built around fossil fuels so they can run on renewable energy will require far more copper — the essential artery of power networks and electrical equipment — than the companies able to produce it are currently equipped to deliver. It’s far from clear whether a traditionally cautious mining industry will embrace the scale of investment needed to rewire the world. Failure would throw the energy transition off course.

1. Why is copper so important right now?

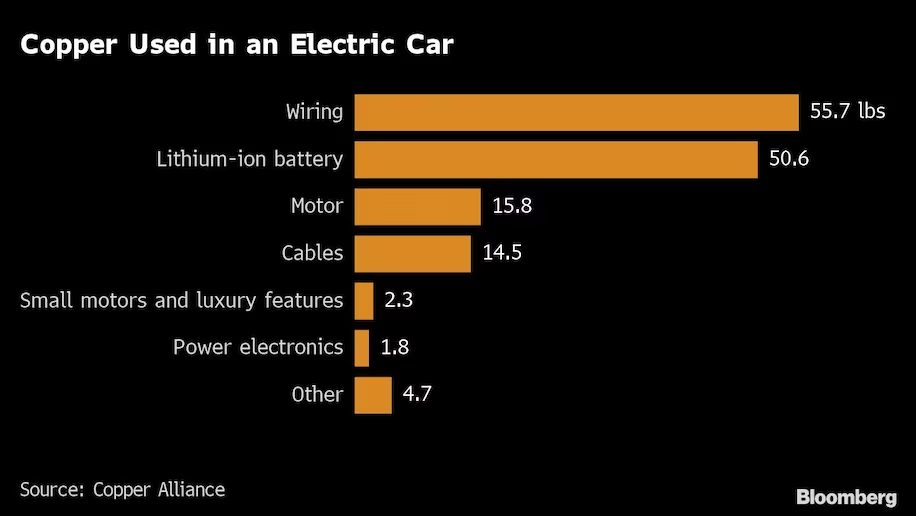

Copper is an efficient electrical conductor that’s relatively abundant, and there’s no obvious substitute. You can find it in all kinds of products, from toasters to air conditioners and computer chips. There are about 65 pounds (30 kilograms) of copper in the average car and more than 400 pounds in the typical home. Decarbonizing power networks, transportation and industry will require far more of it than is currently available. Millions of feet of copper wiring are needed to build the denser, more complex grids that can handle electricity produced by decentralized renewable sources and balance out their intermittent supplies. Solar and wind farms require a lot more copper per unit of power produced than centralized coal and gas-fired power stations. Electric vehicles use more than twice as much copper as gasoline-powered cars, according to the Copper Alliance. As a result, annual demand is set to double to 50 million metric tons by 2035, according to an industry-funded study by S&P Global. That assumes enough of the red metal will become available, which is far from certain.

2. Why is that?

Recycling more copper won’t bring enough new supply into the system, so the only alternative is to dig more out of the ground. But growth in supply is forecast to peak as soon as 2024 as fewer new mining projects come online and existing sources dry up. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimates that miners need to spend about $150 billion in the next decade to overcome an 8 million-ton deficit. (For context, the global deficit in 2021 was just 441,000 tons, equivalent to less than 2% of demand for the refined metal, according to the International Copper Study Group.) Current worst-case projections from S&P Global show a shortfall by 2035 equivalent to about 20% of consumption.

CHART: Copper exploration budgets jump, but major discoveries elusive

3. Why can’t miners just boost production?

These companies got badly burned in the past when the industry cycle turned and they found themselves boosting output just as demand was falling. Since then, they have prioritized strong balance sheets and become more wary of investing in new projects. The specter of global inflation makes heavy capital spending even less palatable as it pushes up operating and borrowing costs. What is more, rich copper deposits are getting harder, and more expensive, to find. And increased scrutiny of mining’s social and environmental standards has raised production costs and placed more barriers to expansion.

4. How is this playing out already?

Just as oil took center stage in the geopolitics of the last century, copper is becoming a national security issue in this one. Governments are hurrying to lock in future supplies for their fast-growing clean-energy industries. Copper’s supply chain is currently skewed toward China, which processes and consumes a large chunk of the metals extracted in Latin America and Africa. China’s dominance in metals like copper, lithium, and cobalt has helped it to become the leader in manufacturing electric vehicles. Its economic rivals such as the US and Germany are now looking to source more of those metals locally or among their allies. Some US lawmakers have advocated that copper should be added to a list of minerals deemed critical to the US.

5. What if there’s not enough copper to go around?

If supply shortages turn out to be as severe as some analysts predict, it would cause a surge in prices that risks damaging the economics of smart grids and renewables and slowing their adoption. Manufacturers of clean-energy technologies could help themselves by finding ways to use less copper in their products. And higher prices would give miners at least some incentive to ramp up production. But it takes several years to develop a new mine, so even if a burst of new demand gave miners the confidence to embark on massive new investments, it would take about a decade to move the needle on output.

6. Will copper producing nations play along?

National politics could put a brake on new supply. Countries with large reserves of metals are pushing for a bigger share of the profits from mining to address economic inequalities, which could discourage some investment. Bureaucratic hurdles can also get in the way. In Chile, the world’s biggest copper producer, mining projects have been held back by regulatory uncertainties. In Panama, a major mine is embroiled in a tax dispute. Environmental damage is another risk for nations weighing new mining projects. Copper is extracted from ore using chemicals that can enter groundwater, contaminate farmland, kill wildlife and pollute drinking water. Copper tailings — the waste rock left over after the ore is processed — are set to grow from an annual rate of 4.3 gigatons in 2020 to 16 gigatons in 2050, according to researchers at the University of Queensland in Australia. That’s not just an environmental problem: The additional storage cost could amount to $1.6 trillion, the researchers estimated.

(By James Attwood)

2 Comments

Michael James Bue

There have been panic in the Cu market during past cycles. Plenty of Cu in the ground and higher Cu prices will provide the finance for development. A higher Cu price will also result in the use of Al as a replacemnt in electrical circuits. All the hoha about the Cu shortage is just another cycle of opportunity for brokers to push up the price.

Edward Gates

Higher copper demand will lead to higher copper price. At some point, an equilibrium will be reached where only the more wealthy will be able to afford green energy, and the rest of the world will continue with fossil fuel. There is a lot of potential copper production that is being stopped by governments, environmental groups and indigenous communities. The “mine in someone else’s backyard” mentality.