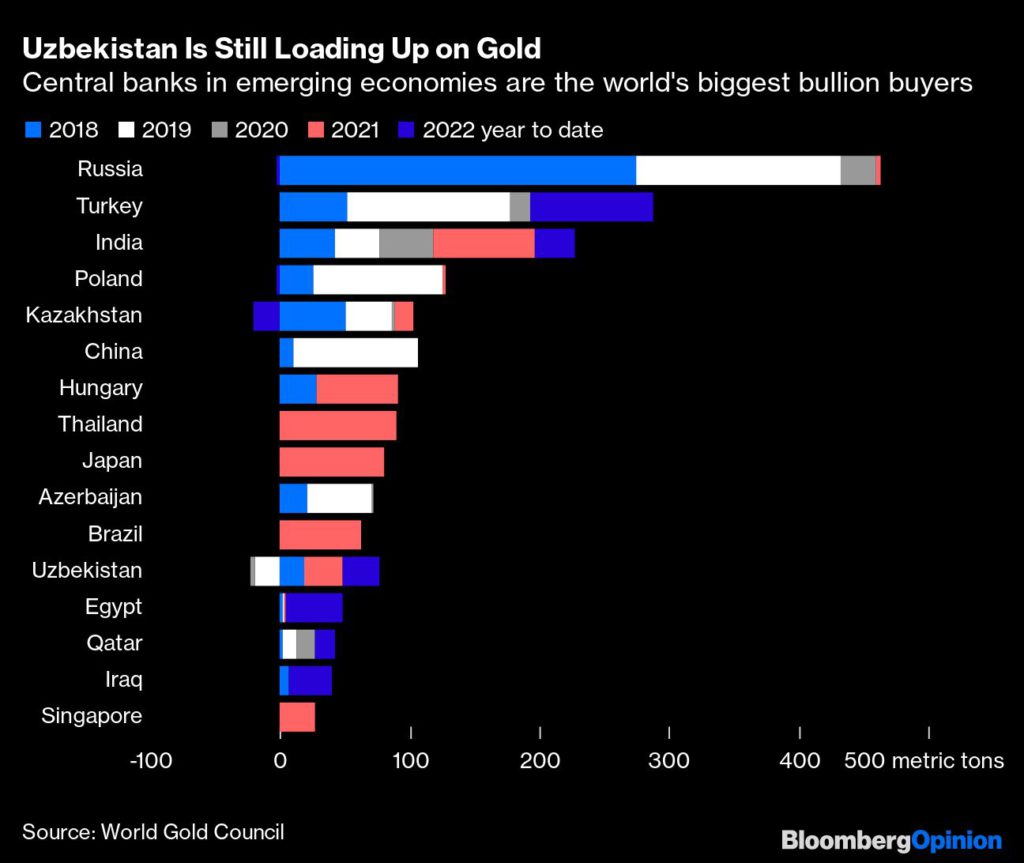

The world’s second-biggest buyer of gold among central banks last quarter believes there’s hardly such a thing as too much bullion.

Uzbekistan has brought the share of the precious metal in its $32 billion reserves to almost two-thirds, in a reversal of a plan to cut it below 50% by buying US and Chinese sovereign debt.

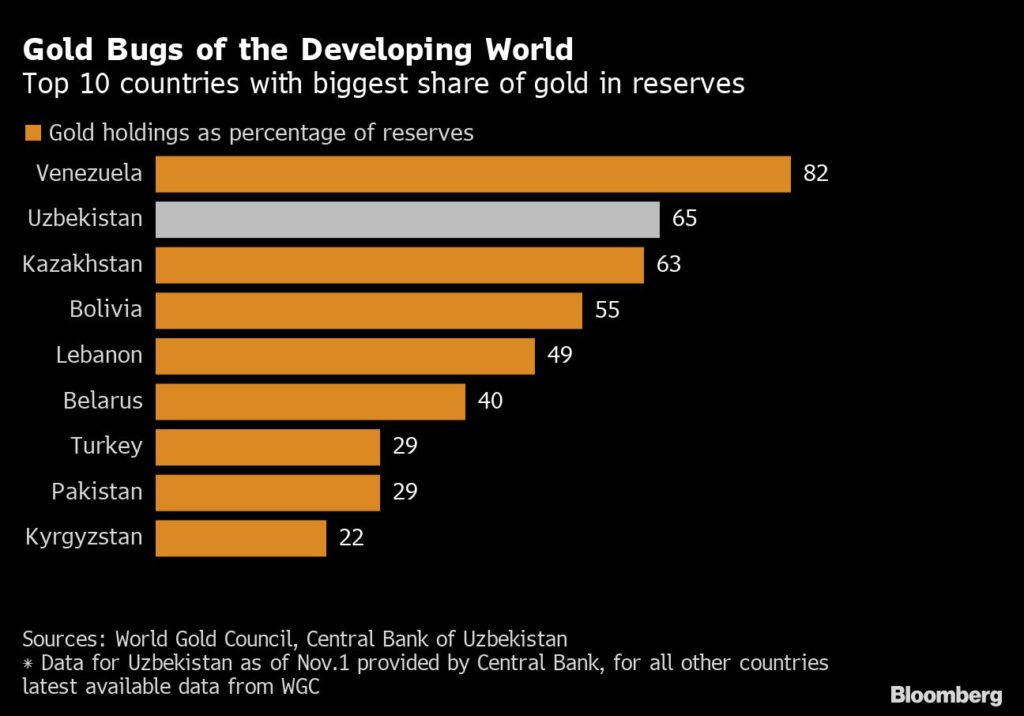

The proportion is now among the highest in developing economies tracked by the World Gold Council, even as total Uzbek reserves have grown by about a quarter since the central bank broached the idea of diversifying away from bullion more than three years ago.

“We thought about investing in Treasuries, but then the market itself didn’t let us do it,” the Uzbek central bank’s deputy chairman, Behzod Hamraev, said in an interview.

With gold prices surging to a record in 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic, Hamraev said the central bank changed course. “Prices were really good and we continued with gold,” he said in the Silk Road city of Samarkand.

Central Asia’s most populous nation has stood out this year even as central banks scooped up a record of almost 400 tons of gold last quarter, more than quadruple the amount a year earlier, according to the WGC, a lobby group for the mining industry. Uzbekistan’s purchases of 26 tons were second only to Turkey’s.

Gold’s appeal as a safe haven for investors has grown after sanctions imposed this year on the central bank of Russia, Uzbekistan’s second-biggest trading partner, over the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine. While penalties levied by the US and its allies cut off Russia’s access to about $300 billion of reserves held in foreign currencies such as dollars and euros, bullion remained largely beyond their reach.

Gold again rose above $2,000 per ounce in March as global inflation shocks fueled demand for the metal as a hedge. Since then, the US dollar has rallied and Treasuries have sold off as the Federal Reserve aggressively hiked interest rates. Meanwhile, gold declined for seven straight months in the longest losing streak since at least the late 1960s.

As prices peaked in the first quarter, the Uzbek central bank offloaded 50 tons, sales that were partly offset by domestic purchases at the same time. It hasn’t offered bullion in the market since then, in anticipation that the outlook will improve.

“There are two factors for us: the current price and the future price,” Hamraev said. “Is the price rising, or has it reached its peak and is coming down? This is the moment we are looking for. If the price is rising, we are better off waiting with sales.”

Uzbekistan, which became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991, ranks 11th among top gold producers globally.

The central bank buys the entire local output of more than 100 tons a year, paying producers in the local currency and selling dollars to offset the impact of the purchases. It’s already acquired 86.5 tons in the first 10 months of the year, raising its holdings near 399 tons.

Though gold historically tends to do well during periods of turmoil, this time may be different because global central banks have no intention of propping economic growth, Hamraev said.

“Usually as soon as a crisis starts, gold rallies,” he said. “Will it happen when the liquidity is shrinking? That’s the big question.”

Hamraev said in jest that he wouldn’t be “bothered” if all of Uzbekistan’s reserves were in gold, a scenario that “logically can’t happen” since the central bank needs to hold on to some cash. One of the mechanisms to avoid the ill-timing of gold sales is to conduct swap operations with Uzbekistan’s sovereign wealth fund, he said.

As for its own cash, the central bank parks it in deposits.

“The rates are really good right now, better than the Treasuries,” Hamraev said. “This is the tradeoff: the gold price is lower, but the deposit rates are good.”

(By Nariman Gizitdinov and Maria Kolesnikova)

Comments