Something is amiss in Brazil’s biggest carbon market.

At best, the program known as RenovaBio that mandates fuel distributors purchase biofuel credits is “asymmetrical” and “inefficient,” with an expected shortage of credits driving prices to more than triple since the start of the year, said Joisa Dutra, a professor at the Fundacao Getulio Vargas business school who has studied the program. At worst, its sharpest critics say, the program overpromises on emissions impact, ignores international standards and risks shrinking the potential market for other carbon credits — ones they say could more directly help the country meet its climate goals.

“They are not removing any kind of greenhouse gas emissions at all,” said Patrizia Tomasi-Bensik, an engineer who does contract work for a UN climate agency and is arguably the program’s loudest critic. “It’s a huge scheme.”

RenovaBio, signed into law in 2017 as an incentive to expand biofuels production, is an important part of Brazil’s plan to cut greenhouse gas emissions 50% by 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2050, the country’s energy ministry said in response to questions. As it points out, a Brazilian flex-fuel car running on ethanol produces less carbon dioxide per mile than European electric vehicles. Fuel distributors avoided emitting 24 million tons of greenhouses gases in 2021 thanks to the program, Brazil’s energy ministry said. In short, leaning into biofuels like sugarcane ethanol as a solution to climate change given the nation’s position as a global agricultural powerhouse just makes sense, advocates of the program say.

The program exemplifies just how hard it is to satisfy all parties when trying to meet climate pledges set under the Paris Agreement. Bite off too ambitious a goal and the project may fail; take too small a step forward and critics will cry greenwashing. And unlike other publicly traded commodities such as a barrel of oil or an ounce of gold, there is an ongoing debate over how to even measure a ton of carbon removed from the atmosphere in the first place. That means every attempt to quantify it is under the microscope — and in an increasingly ESG-minded world, not all carbon-reduction schemes will ultimately pass muster.

The way this specific program is set up, biofuels producers and importers generate decarbonization credits, known as CBIOs, representing a ton of carbon that would have been emitted by an equivalent amount of fossil fuels. In turn, fossil fuel distributors are required to buy the CBIOs to meet their decarbonization targets. The credits began trading in 2020.

But the program is running into some problems — big or small, depending who you ask. For one, it’s lopsided: The government sets a target for the number of CBIOs that need to be purchased, but there’s no corresponding quota for the number that need to be created. That’s leading to a squeeze on availability and driving prices to skyrocket — an added cost for fuel distributors that inevitably trickles down to the consumer in the form of higher gasoline prices, though probably only a few centavos a liter. At current prices, fuel distributors will need to spend about 7.5 billion reais ($1.4 billion) on CBIOs next year to meet the government’s target, more than sixfold what it cost them last year.

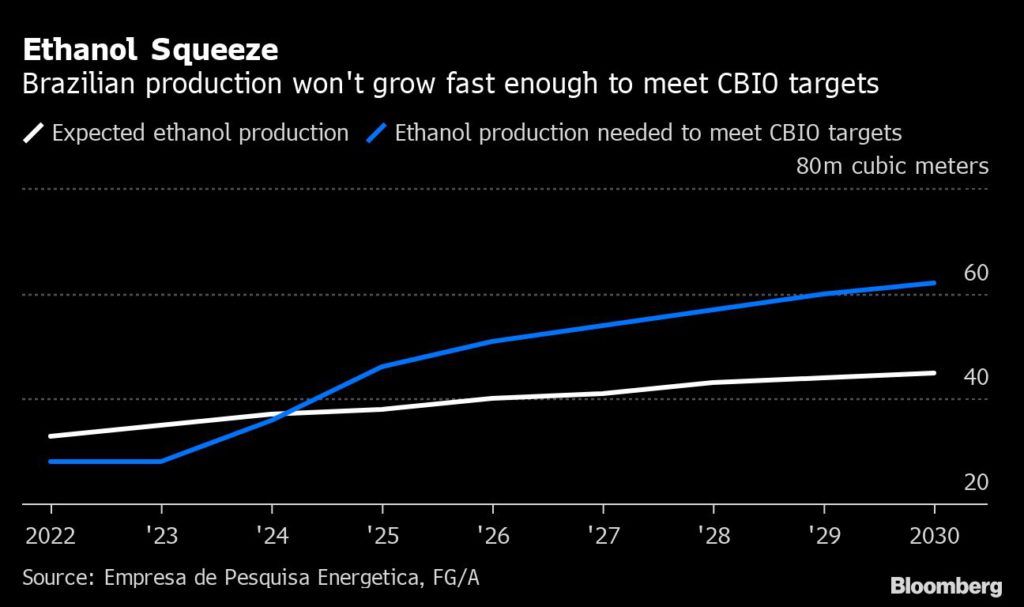

Why are prices going up? For one, fuel distributors are required to buy 45% more of these credits this year than in 2021, but the production of biofuels has actually been declining since 2019. Brazil’s main sugar industry association, Unica, contends ethanol producers are on track to supply enough CBIOs to meet demand this year; still, fuel distributors are getting nervous about the future. According to estimates from FG/A, a consulting firm based in Sao Paulo state, Brazil’s ethanol output must almost double by 2026 to meet CBIOs targets, an unlikely scenario as there are no major ethanol expansions in the works.

In fact, some fuel distributors are likely already buying for 2023 to avoid any shortages, said Plinio Nastari, the president of consultancy Datagro. To be sure, if credit prices do stay elevated, it could encourage mills to produce more ethanol, potentially increasing supply by 5 billion or 6 billion liters per year, said FG/A partner Willian Hernandes. Higher credit prices could even trigger new ethanol projects, boosting the biofuel production to meet long-term goals, he said. Going forward, Unica said it expects ethanol producers to both certify a greater percentage of their production with RenovaBio and produce more ethanol from the same amount of sugarcane.

But if major gasoline subsidies were to become a reality — something other countries are increasingly doing to keep costs in check — it would make ethanol less competitive, encouraging mills to prioritize sugar instead and worsening the disconnect between credit supply and demand.

Beyond the supply and demand mismatch, the program has other key flaws, critics say. For one, it’s based on the premise that Brazilian ethanol produces far less carbon dioxide than gasoline — about 90% less, according to Unica, citing a study from the US Environmental Protection Agency. But Tomasi-Bensik — who’s on the roster of experts advising the Clean Development Mechanism’s assessment team, a part of the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) — says she calculates it’s only 21% cleaner when taking into account emissions from rotting plant waste left on the field. Unica disputes that math.

Tomasi-Bensik has been railing against RenovaBio for years. She wrote a book accusing Brazil’s politically influential sugarcane growers of shaping the legislation and reaping the financial rewards while doing little to curb global warming. She even filed a lawsuit last year against top Brazilian officials who helped draft the law. The greenwashing case was quickly thrown out by a judge. In her reading of the program, “you are making people buy something that is fake,” she said. “They discredit the whole market.” UNFCCC didn’t reply to multiple requests for comment on whether it shares her opinion.

Others are also critical of the program, mainly because they say it shows how easy it is to overlook the international standards that UNFCCC has spent decades to define. A key rule known as additionality, or the reduction of emissions below what would have occurred in a business-as-usual scenario, isn’t a requirement in Brazil. The UNFCCC also rejects biofuels projects from land that could be used to grow food.

Read more: Carbon offset trading is taking off before any rules are set

Shigueo Watanabe, a physicist and collaborator at ClimaInfo, an organization that focuses on climate change information and education, was hired by Brazil’s energy ministry to consult on RenovaBio leading up to its approval. Watanabe said he suggested that the government should split CBIOs into two classes: one that includes additionality and a class that doesn’t. “I disputed that with the people in the process,” he said, noting that his suggestion didn’t make it into the final bill.

Brazil’s energy ministry declined to comment on the lack of additionality in CBIOs, which are formally called decarbonization credits.

“In the end, it’s a carbon tax,” said Adriano Pires, one of the program’s supporters and the director CBIE, a Rio de Janeiro-based infrastructure consultancy. “There need to be more countries using sugar for ethanol.”

(By Peter Millard and Tatiana Freitas)

Comments