Official Chinese economic statistics for May told a story of a lockdown-wounded economy improving on the back of stronger industrial output and investment – but a deeper look suggests an economy still contracting.

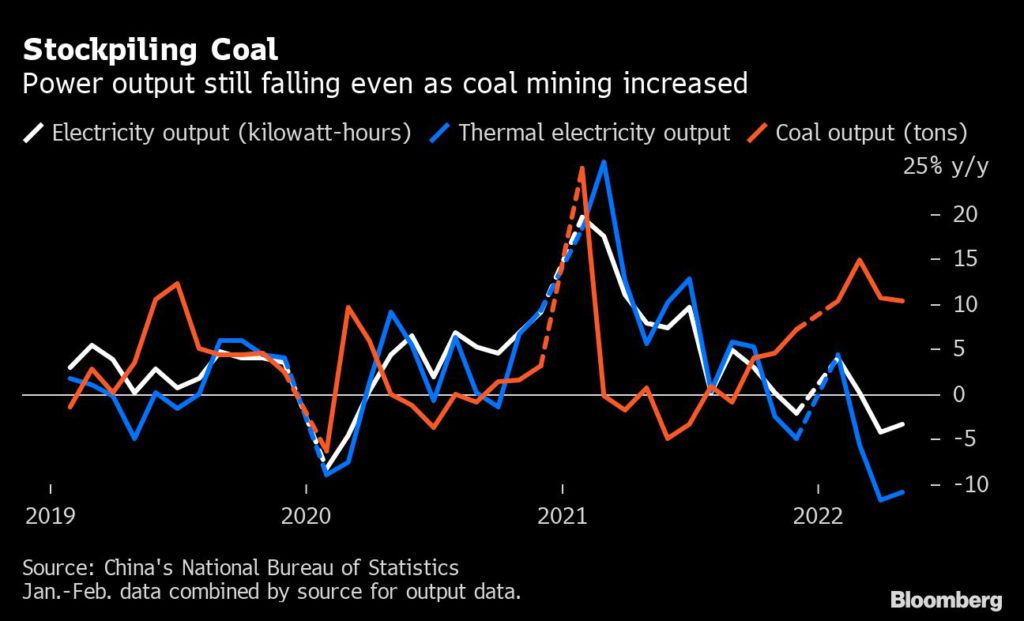

Headline industrial output in May grew an unexpected 0.7% from a year earlier, but the output of electricity was down 3.3% and power consumption was down 1.3% for the same period, according to government data released Wednesday. While gross domestic product data for this quarter won’t be released until July, that gap and other high-frequency data points to an economy that was still shrinking.

“We believe some fundamentals might be worse than the official data suggest,” economists at Nomura Holdings Inc. wrote in a note, pointing to falling production of power, cement, crude steel, autos and smartphones, and also an index of road freight which was almost 19% lower than a year earlier. That decline may have continued into this month, with truck activity down more than 20% in the first two weeks of June compared to the same period in 2021, according to G7 Connect, a digital logistics firm.

The gains for the industrial sector were concentrated in energy, specifically the output of coal, which grew more than 10% in the month. Sectoral data showed that production gains were concentrated in the mining sector, where output rose 7% on year, faster than the 0.1% gain for China’s much larger manufacturing sector. Of the 17 kinds of industrial goods tracked by the NBS, the output of 10 of them fell year-on-year in May. Output of cars, for example, fell nearly 5%.

“Production and supply of electric and heat power fell 0.8% y/y, after growth in April, which doesn’t seem consistent with factories coming back online,” said Craig Botham, chief China economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

With coronavirus lockdowns limiting consumer spending, China’s President Xi Jinping has promised “all out” effort to boost infrastructure spending to support the economy. However, there were few signs of that in the May data.

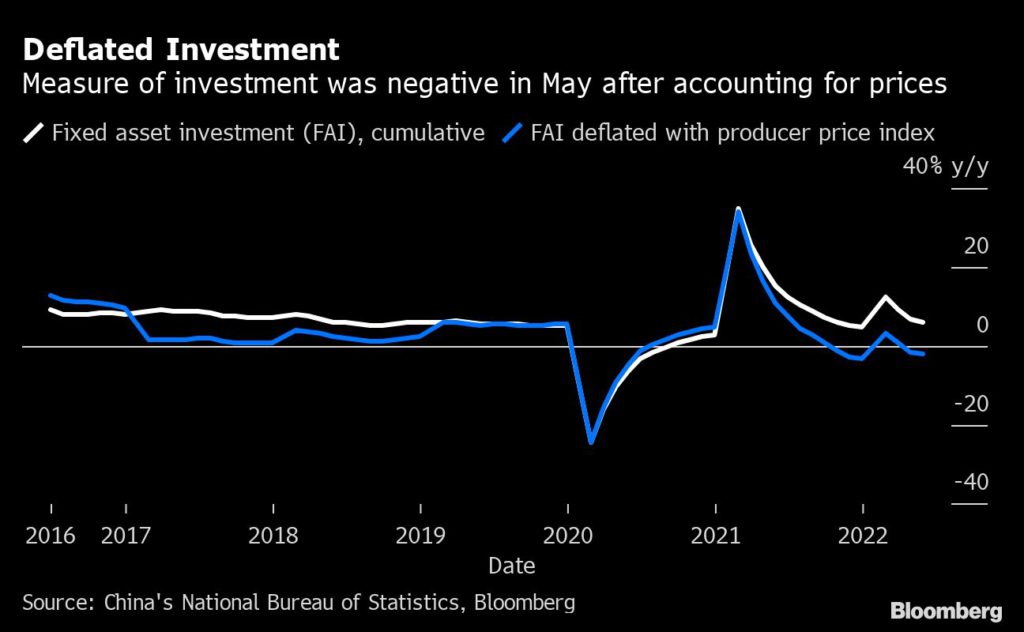

The headline figure for fixed-asset investment looked impressive at 6.2% growth if the first five months of this year. But with producer prices rising by around 8%, that means spending saw a fall in real terms in May. A big part of slowdown is the ongoing slump in the real-estate sector: new property construction starts were down almost 42% on year.

The figure for infrastructure investment was a more impressive – but that is belied by the 17% drop in cement output or the nearly 8% fall in the sale of construction materials.

That discrepancy is likely partly due to a quirk in how fixed-asset investment is calculated – it doesn’t necessarily correspond to spending on construction. For example, if a firm buys a second-hand manufacturing machine from another company, the full value of the purchase would be included as FAI even though it adds less than that to GDP. The investment data also includes land purchases.

Backdated payments to suppliers could also distort the FAI figures, according to economists at HSBC Holdings Plc. Some money that is being counted as new investment has actually been state-owned enterprises paying off debts to privately-owned companies, the economists wrote in a note.

China’s retail sales fell 6.7% year-on-year, as lockdowns curbed household spending and people saved more. But inflation apparently flattered that figure: among the biggest gains by-product was spending on petroleum, which rose 8%.

Retail sales are less of an indicator of household spending, as China’s consumers spend an increasing share of their income on services as they become wealthier. Official data for spending on restaurants and catering showed a sharper year-on-year decline than for overall retail sales, dropping 21% for a third straight month of falls.

“Even the most charitable analysts accept that the National Bureau of Statistics smooths the GDP data by understating weakness during downturns,” according to Mark Williams at Capital Economics. “We already saw signs in the first-quarter data that the full extent of weakness in the service sector was not reflected in the GDP figures.”

(By Tom Hancock, with assistance from Dan Murtaugh, Yujing Liu and Xiao Zibang)

Comments