Gold is among the safest of havens in times of war, or any other type of geopolitical instability.

During the 1970s, which saw a number of upheavals in the Middle East including the Iranian Revolution, the Iran-Iraq War, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, gold rose 23% in 1977, 37% in 1978, and 126% in 1979, the year of the Iranian hostage crisis.

Gold also spiked when the US bombed Libya in 1986, when Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, after 9/11, and when the US attacked Iraq in 2003. More recently, in 2020 gold reached $2,034 an ounce on fears of the coronavirus spreading and causing economic devastation.

While gold has since pulled back, on speculation that the US Federal Reserve would raise interest rates (last week it did, hiking the overnight lending rate by 0.25%) to tackle record-setting inflation (currently 7.9% in the US), the precious metal once again returned to safe-haven status following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

After the US and the UK announced bans on Russian oil imports, on March 8 spot gold touched $2,051 per ounce, the highest since August 2020 when the metal reached its all-time peak of $2,072.50.

The Russia-Ukraine war, unthinkable mere weeks ago, has alarmed NATO countries on Russia’s western flank, that one of them could be next. A Russian missile attack that killed 35 people in western Ukraine, just 15 miles from Poland, introduced the possibility of an errant missile or bomb landing on a NATO member (Poland, Romania, Hungary and Slovakia, all bordering Ukraine, are all part of NATO), thus widening the conflict. By NATO’s constitution, an attack on one member is an attack on the entire defensive alliance.

Days after Russia launched an invasion of its pro-Western neighbor, Vladimir Putin ordered his country’s nuclear forces be put on high alert. Suddenly the possibility of World War III seemed no longer far-fetched.

Setting aside the apocalyptic scenario of a nuclear exchange, the threat of a prolonged conflict in Ukraine including Russia invading European countries (or former Soviet vassal states) has jolted NATO countries out of their post-1989 stupor, leading to a re-think of military spending and the age-old “guns versus butter” debate.

The guns versus butter model portrays the relationship between a nation’s investment in defense and civilian goods. Because a country has finite resources, it must choose how much to spend on defense/ the military (guns), against the amount budgeted for items that are needed for non-defensive purposes (butter). Of course, it can also buy a combination of both.

The United Kingdom is a good example of a country that is currently having this guns vs butter debate.

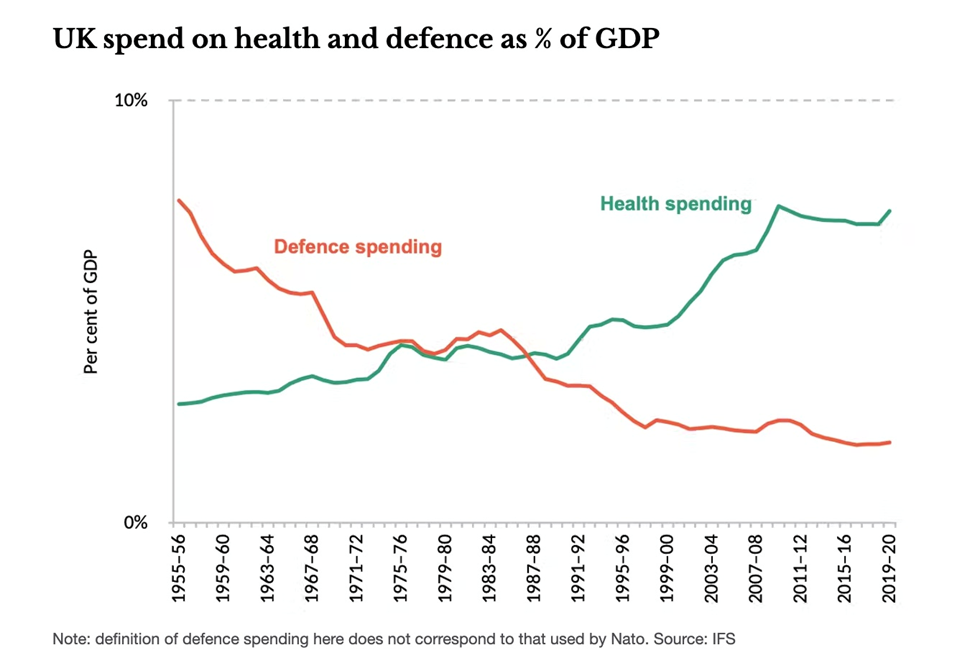

The “peace dividend” from lower spending on defence over the past several years has allowed successive UK governments to pay for a growing welfare state. The country now spends a little over 2% of GDP annually on defense, but it wasn’t always this small. In the mid-1950s the UK spent 8%, falling to about 4% in 1980 and 3% in 1990. In comparison, government spending on the National Health Service rose from around 3% of GDP in the mid-1950s to over 7% by 2020.

Will the Ukraine war force the UK government to re-order its priorities so that more is spent on the defence of Europe? The answer isn’t straight-forward. As The Conversation notes, Britain is already the second largest spender in NATO (US$73 billion in 2021) after the United States ($811 billion). In fact the constitutional monarchy is one of only a handful of countries to have consistently met the NATO pledge, that each member spend 2% of GDP. Recall President Trump’s beef with Germany that it wasn’t pulling its weight in NATO, by only spending 1.3% of GDP. Other European NATO members who have consistently under-contributed to the NATO target, include France (avg. 1.9%), Italy (1.2%) and Spain (0.9%).

However, German Chancellor Olaf Scholtz has just promised to invest €100 billion in the German military and to spend at least 2% of GDP in every year going forward. Other countries including Denmark and Norway, are talking about following suit.

If Germany succeeds in meeting its 2% of GDP target, for Britain to maintain its position in NATO as number 2 top spender, it needs to boost its own defense spending by about 20%. The Conversation calls that a substantial sum. If nothing else, Germany upping the ante will pressure the UK to cancel planned defense cuts over the next three years.

It’s worth delving a bit deeper into Germany’s increasing militarization, given the history. After World War II ended in Germany’s defeat, there was much debate about whether it should even be allowed to have armed forces. When the Budeswehr formed in the mid-1950s, its sole purpose was to defend West German territory, not to fight abroad.

The latter has changed since re-unification, with Germany deploying troops overseas, but sensitivities remain. The BBC reminds us of an alleged cover-up in Afghanistan in 2009, after a military strike involving German forces caused civilian deaths.

Two days after Russia invaded Ukraine, Germany reversed a historic policy of never sending weapons to conflict zones. The government said it would send 1,000 anti-tank weapons and 500 Stinger anti-aircraft defense systems to Ukraine, authorized the Netherlands to deploy 400 rocket-propelled grenade launchers, and told Estonia it would ship over nine howitzers.

Last week Scholz went a step further, as mentioned promising to spend 100 billion euros on upgrading Germany’s military, including €44 billion for fighter jets and ammunition. The country has already ordered 35 American F-35 fighter jets made by Lockheed Martin, to replace its aging Tornado combat planes, Reuters said, adding that investment in more nuclear weapons is likely.

Poland and the UK are also in the mix of new defense spenders, with the former planning to buy MQ-9 Reaper drones and Britain budgeting $700 million on a US defense system. Jefferies analysts quoted by Reuters say that NATO needs to shell out an additional €62 billion per year, just to meet its 2% of GDP spending requirement.

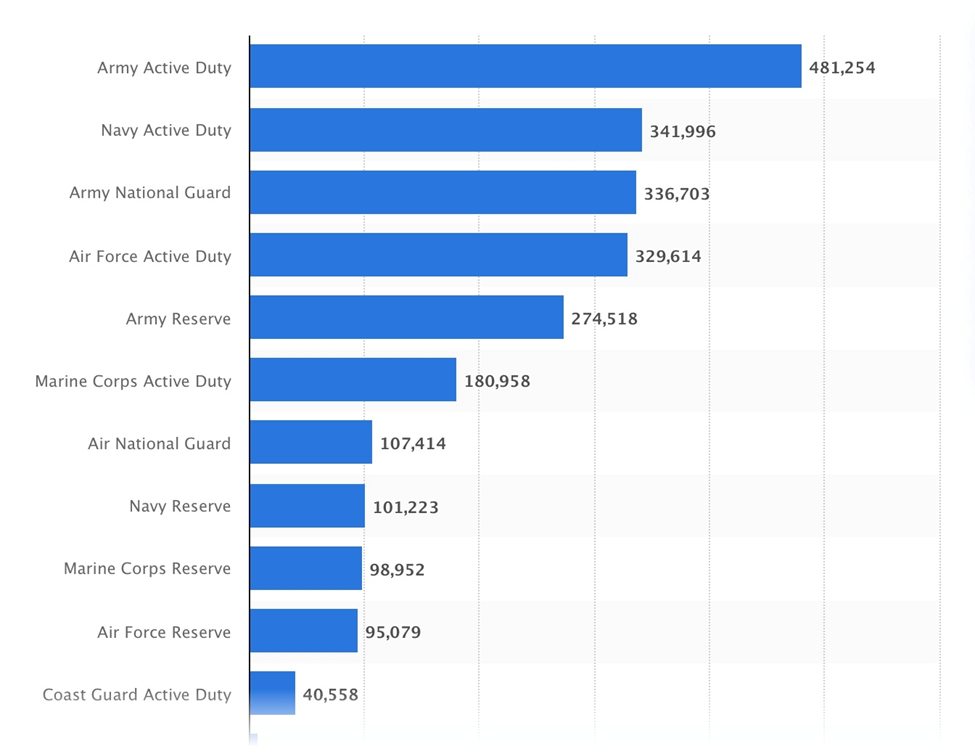

Scholz’s decision more than doubles Germany’s defense budget, which was only €47B in 2021. Still, it’s a long way from what the US spends. According to Breakingviews, via Reuters, the United States as top military power spends 10% of its budget on defense and has 2.3 million personnel, amounting to 0.7% of its population. The German ratio is just 0.25%. Bringing that into line with America would require an extra €14B, assuming an average salary of €37,000.

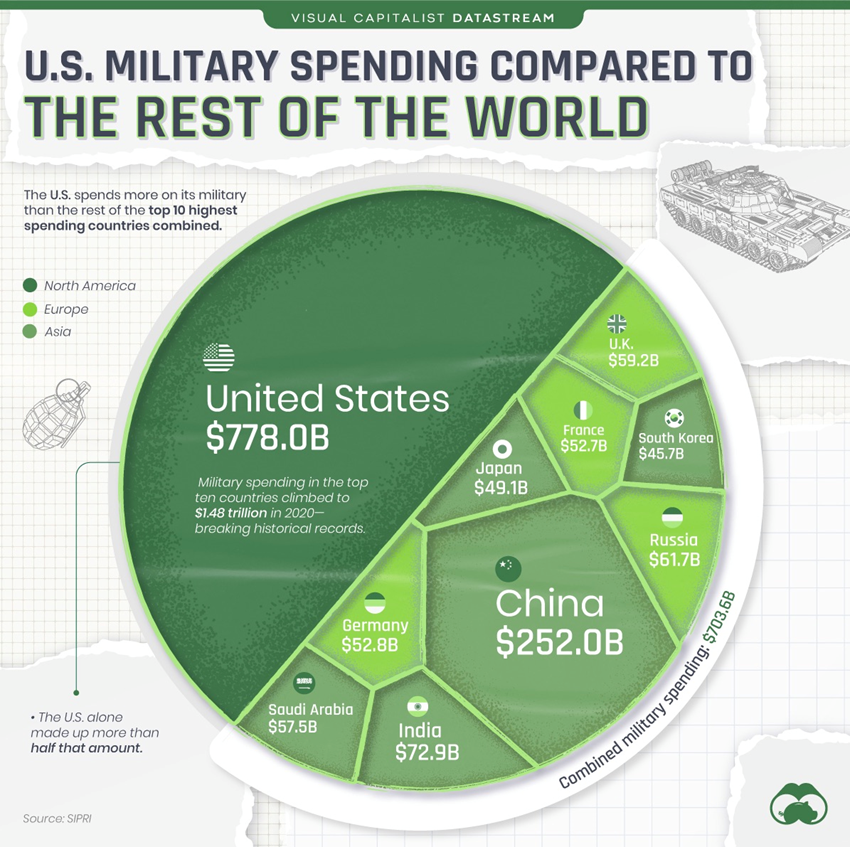

In 2020 the US spent $778 billion ( does not include costs for its nuclear force or veteran benefits) on military spending, more than the next nine countries combined. Defense spending reportedly accounts for more than 10% of all federal spending and nearly half of discretionary spending.

According to World Population Review, the 10 countries with the highest military expenditures are:

However, the US military is not the world’s largest; its 1.388 million active personnel are outnumbered by India’s 1.455 million and China’s 2.185 million. Another 1.037 million are in the National Guard and reserves.

That bring up another interesting statistic. When reserves or paramilitary service members are counted, the American military falls to seventh place in the world. The countries with the highest number of military personnel, are, in order, Vietnam (10.5 million), North Korea (7.7M), South Korea (6.7M), India (5.1M), China (4.0M), Russia (3.5M), and the US (2.1M).

While the United States and the rest of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization have refused to impose a no-fly zone over Ukraine, which would require them to shoot down Russian warplanes, the US hasn’t shied away from providing military aid to Ukraine.

Notably, even before the war began, President Joe Biden asked Congress for a US defense budget exceeding $770 billion for fiscal 2022-23, an amount higher than the budget requests by former President Trump.

As Commander in Chief of the armed forces, Biden on March 17 announced $800 million in military equipment would be transferred directly to Ukraine, bringing total US military aid since the Russian invasion began to $1 billion. His administration previously approved another $1 billion in aid before the invasion.

The latest package includes anti-aircraft, anti-tank weapons and drones. Specifically, there are 800 Stinger anti-aircraft systems that can be used to defend against helicopters and low-flying aircraft using infrared sensors; 2,000 Javelin shoulder-mounted weapons guided by computers to hit tanks; 100 Tactical Unmanned Aerial Systems (drones); and a multitude of lighter weapons including 100 grenade launchers, 5,000 rifles, 1,000 pistols, 400 machine guns, 400 shotguns, along with body armor, helmets and ammunition, Al Jazeera reported.

It’s interesting to note, as the Wall Street Journal did Monday, that Washington is also sending to Ukraine, some Soviet-era air defense equipment it secretly acquired decades ago. The Ukrainian military already has such equipment but it needs more of it. According to WSJ,

The shoulder-fired Stinger missiles that the U.S. and NATO nations are providing to Ukraine are only effective against helicopters and low-flying aircraft.

The U.S. is hoping that the provision of additional air defenses will enable Ukraine to create a de facto no-fly zone, since the U.S. and its NATO allies have rebuffed Ukraine’s appeals that the alliance establish one.

So far, the war has shown the fortitude of Ukraine’s military, many of whose soldiers have been battle-hardened fighting Russians in eastern Ukraine. Realistically though, their chance of success is low, considering the extent to which Russia outspends and outnumbers them.

Ukraine’s military spending in 2020 was just $6 billion, about a tenth of Russia’s $62 billion. There are 900,000 active Russian military personnel compared to Ukraine’s 209,000, and Russia can call upon an additional two million reservists, versus Ukraine’s 900,000. The Russian army has quadruple the number of tanks as Ukraine, and there is an even greater imbalance in term of armored vehicles and artillery. Russia has over 500 attack helicopters and 1,500 fighter jets, compared to Ukraine’s 34 attack helicopters and 98 jets.

In a piece published immediately after the invasion, the National Post states, [t]he military strategic context has also changed in just the past five years, as a survey of military capability shows. The very fact that Russian President Vladimir Putin can deploy more than 100,000 troops to the Ukraine border regions, and 30,000 in the allied former Soviet state Belarus, marks the fruition of Russian military investment over the last 15 years or so, since Russia’s war in Georgia to reclaim influence over Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

During the hottest moments of the last Russian war on Ukraine in 2015, there were approximately 12 Russian battalion tactical groups in action around southeast Ukraine. Today, there are well more than 100 involved in a full-scale invasion from Russia and Belarus, which is close to Ukraine’s capital Kyiv.

How about the world’s second and third-biggest military spenders?

China began building up its military in the mid-1990s, with the goal of keeping its enemies at bay in the waters off the Chinese coast. Long seen to be inferior to the powerful US Navy, including the Japan-based 7th Fleet, the People’s Liberation Army is now the largest navy in the world, its submarines capable of launching nuclear missiles.

Shipyards in China recently launched the navy’s first two Type 075 amphibious assault ships, which will play a role similar to that of the US Marine Corps, giving them the ability, with supporting weapons, to fight in distant conflicts. The 40,000-tonne ships are like a small aircraft carrier with accommodation for up to 900 troops, heavy equipment and landing craft. First renditions will carry up to 30 helicopters, with later versions expected to accommodate fighter jets like the US F-35B. A third Type 075 in November embarked on its maiden voyage and the navy could eventually have seven or more of these ships, according to China’s official military press.

China is also expanding its marine forces, estimated at between 25,000 and 30,000 troops, compared to just 10,000 in 2017. The Pentagon and other Western military experts however say the PLA marines are less capable that the 186,000-strong US Marine Corps, which has extensive experience in amphibious and land operations.

While China has established dominance close to its coast, the United States is considered to have more powerful ships and maintains an overall advantage at sea. For example, China’s 360 ships outnumber the US but they are mostly smaller vessels. The PLAN only has two aircraft carriers and a third under construction, whereas the US Navy has 11 carriers, the most of any country.

On land, the PLA’s ground force has traditionally been China’s foundation for asserting regional power. Its 915,000 active soldiers are nearly double America’s 486,000, according to the latest Pentagon China Military Power Report, cited by Al Jazeera. The army has been stocking its arsenal with high-tech weapons including the DF-41 intercontinental ballistic missile, which experts say could hit any corner of the globe, and the DF-17 hypersonic missile.

China’s air force is now the largest in the Asia-Pacific region and the third biggest in the world, Al Jazeera reports, with more than 2,500 aircraft and roughly 2,000 combat aircraft, according to an annual report by the US’s Office of Secretary of Defense published last year.

Most notably, the air force now possesses a fleet of stealth fighter jets, including the J-20, China’s most advanced warplane. It was independently developed and designed to compete with the US-made F-22.

China is also one of the world’s leading exporters of unmanned aerial vehicles (drones), especially to the Middle East. Its customers include the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

India, meanwhile, is shoring up its military with a 10% increase in expenditures. According to Defense News, this year’s defense budget is $54.2 billion, including $7.4 billion for new weapons purchases, $6.3 billion for the Navy and $4.2 billion for the Army.

Among the top line items:

Of course we can’t forget China’s naval rival, Japan, which has been quietly beefing up its military, too. In October, the Japanese Cabinet approved what Forbes is calling an unprecedented 773.8 billion yen (about $6.8B) in additional military spending. The investments include $861 million to intercept and destroy North Korea and Chinese missiles and bombers; $389 million to procure US-built PAC-3 MSE (Patriot) air defense missiles; $106M on new domestic surface to air missiles, $74 million for vertical missile launch systems for two new frigates; $580 million for three P-1 patrol planes, designed for hunting submarines, plus $192M for additional anti-submarine weapons including torpedoes and rockets; $224.4M on 13 Subaru-Bell UH-2 utility helicopters; and finally, $36M for faster deployment of missiles close to Taiwan.

If you build it, they will come. To paraphrase “If you build it, you will use it.”

As the world’s top militaries receive more funds from their respective governments, who have been scared into opening the defense purse strings by the volatility of global events, and now the reality of a full-blown war in central Europe, the gold price has been rising.

As most investors know, the price of gold is determined by a number of factors, including the value of the US dollar (the dollar and gold move in opposite directions), interest rates (typically the yield on 10- and 30-year Treasury notes), negative real interest rates (determined by subtracting the rate of inflation from the yield), geopolitical uncertainty, demand for physical gold, i.e. bars, coins and jewelry, and demand for gold ETFs, measured by flows of stored gold.

One of the most prevalent themes in the gold market right now is the amount of gold being purchased by central banks. The majority of gold and silver is traded on the Comex, a global derivatives market where precious metals are traded in futures contracts.

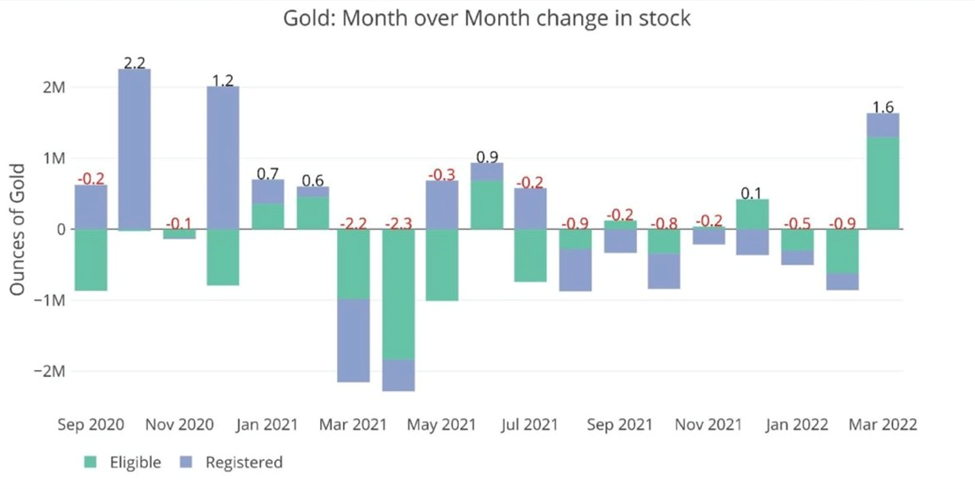

Over the past several months Comex vaults have been steadily depleted (signaling more selling than buying), however, 1.6 million ounces have showed up since March 1, according to a March 18 column by Peter Schiff titled ‘Banks are restocking gold at fastest pace in years.’

Schiff, a gold bug, states“This is the largest inflow since October 2020 and we are only halfway through March!” before coming to the conclusion that “The Comex gold market has been flashing warning signs since early January. This continues to be the case. The latest influx of metal further supports the notion that banks are preparing for higher delivery volume and potentially higher prices.”

Going back further, the trend of central bank gold buying is even more clearly defined. In 2021, the gold that CBs held in foreign exchange reserves rose to a 31-year high.

According to the World Gold Council, via Nikkei Asia, central banks have built up their gold reserves by more than 4,500 tons over the past decade. As of last September, reserves totaled around 36,000 tons, the most since 1990 and up 15% from a decade earlier.

Thailand was the top gold purchaser during the first nine months of last year, at 90 tons, followed by India (70 tons) and Brazil (60 tons).

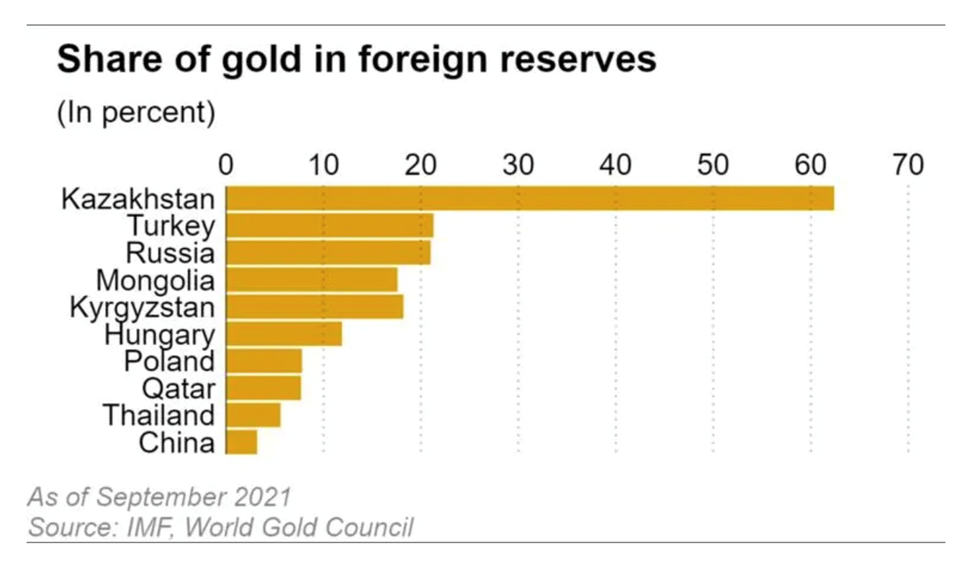

Nikkei Asia identified an interesting gold-buying sub-trend. While large gold purchases have previously been limited to countries like Russia and Turkey, that were (and are) trying to reduce their dependence on US dollars, recently the banks of emerging economies and smaller Eastern European countries have seen the appeal of bullion. These countries are buying gold to avoid being exposed to steep plunges in the value of their currencies. For example Kazakhstan, faced with persistent currency depreciation, sharply raised the ratio of gold to foreign exchange reserves. The chart below shows other countries that have done the same, including Hungary, which a year ago trebled its gold reserves to more than 90 tons.

Is there a connection between increasing global conflict, and higher military spending, on gold? We see two points of contact. First, gold is a safe haven in times of political or economic uncertainty. The second is that military spending feeds debt.

Defense is the largest portion of the US federal budget behind Social Security. These two items are increasing the debt exponentially, adding deficit after deficit to the mounting pile, which, when combined with covid-related government spending, sits at a jaw-dropping $30 trillion.

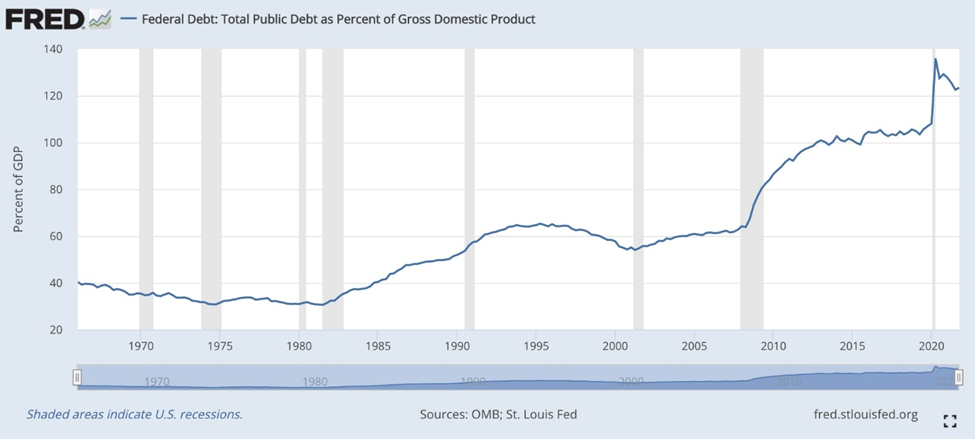

We know from a previous article that gold closely tracks the debt to GDP ratio, arrived at by dividing a country’s total GDP by its total debt. The US debt to GDP ratio has been rising steadily since 2010. It currently sits at 125.6%. As the debt-to-GDP-ratio rises, either because of a drop in GDP due to a recession, or a jump in government borrowing that piles up debt, or both, the gold price reacts.

President Biden’s budget for full year 2022 totals $6 trillion, more than any other previous budget. The US government estimates that for FY 2022, revenues will again fall short of expenditures, leaving a $1.8 trillion deficit. Better than the projected $3 trillion deficit for 2021 — almost the same as last year’s $3T — but it still means nearly $2 trillion will be added to the national debt. (CNBC notes the budgetary shortfall this year is equivalent to 13.4% of GDP, the second-largest level since 1945 and exceeded only by 2020 spending)

According to The Balance, The massive deficit threatens other national spending in areas of healthcare, education, infrastructure, as well as long-standing welfare programs like social security, which at the current pace is set to run out in the years between 2034-2037.

Recall our guns versus butter model. A country must decide how

much to spend on defense/ the military (guns), against the amount budgeted for items that are needed for non-defensive purposes (butter). For the United States to remain the “world’s cop”, it will have to maintain its strong military. There can be no letting up.

This obviously comes at a major cost. When defense spending isn’t matched by social spending to address certain inequalities, the effects can be incendiary, especially in the current high-inflation environment, as we pointed out in a previous article.

More immediately, as investors we should pay attention to what is happening around us. Military spending is on the rise globally, and central banks are hoarding gold like it’s going out of style. In these uncertain times, perhaps it would be wise to follow the smart money and do the same. At AOTH, we continue to buy physical gold and silver on the dips and to invest in quality junior resource companies, which historically offer the greatest leverage to rising metals prices.

(By Richard Mills)

Comments