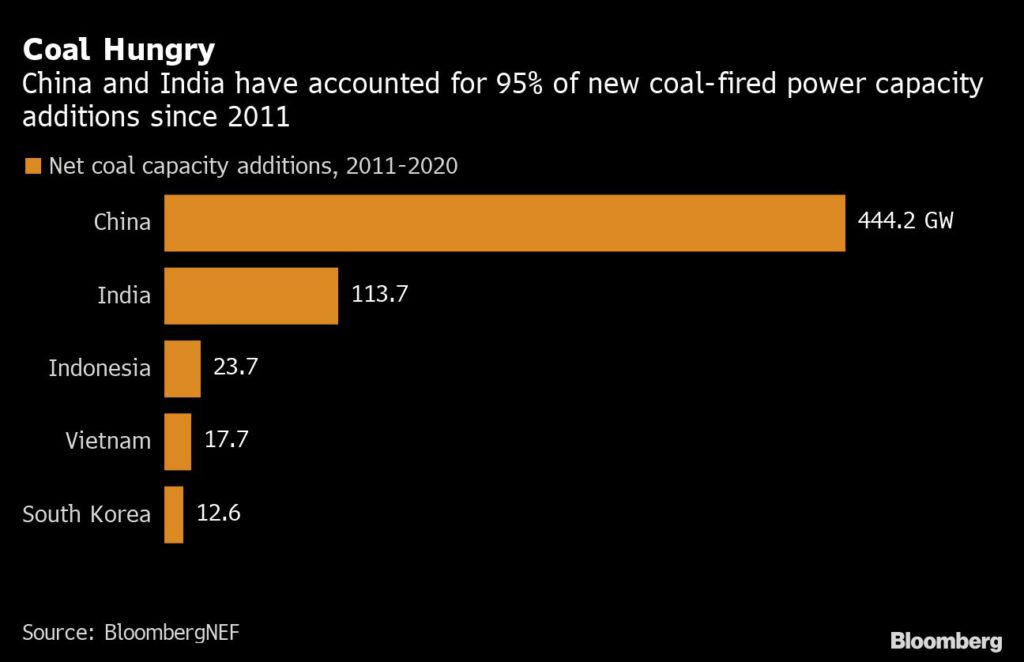

There’s a reason India and China defended coal’s future at the Glasgow climate summit: no nations have added more coal-fired power-plant capacity in the past decade than these two major emitters.

China and India are currently mining a combined 14 million tons a day of the dirtiest fossil fuel. Coal not only remains crucial to their current energy needs but it looks set to have a role for decades to come. That’s even as the two Asian giants install huge volumes of renewables and chase targets to zero out greenhouse gas emissions.

The global pipeline of coal power under development rose last year, the first advance since 2015, driven by a wave of proposed new facilities in China, according to Global Energy Monitor. India’s government forecasts coal plant capacity to grow to 267 gigawatts by 2030 from 208 gigawatts now.

Typically, new coal-fired plants would be expected to operate for at least 30 years, cementing the fuel’s role in the global energy mix beyond the middle of the century.

Negotiators grappled Saturday with last minute changes to the COP26 pact that reduced a call to accelerate the “phase-out” of unabated coal power to a pledge to “phase-down” use of fuel following pushback from India and China. That sparked backlash against the two nations, with COP26 President Alok Sharma saying in a BBC interview that the countries will have to explain themselves.

Meanwhile, mines across China and India have been ramping up production in recent weeks to ease a supply crunch that’s caused widespread power shortages and curbs on industrial activity. China’s miners have beaten a government target to raise output to 12 million tonnes a day, while India’s daily production is close to 2 million tonnes.

“The power cuts since mid-to-late September show that we are still not prepared enough,” Yang Weimin, a member of the economic committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and a government advisor, told a conference in Beijing on Saturday. Additional funding is needed to ensure coal plants can be used to complement a rising share of renewables, he said.

Coal’s share in global electricity generation fell in 2020 to 34%, the smallest in more than two decades, though it remains the single largest power source, according to BloombergNEF.

In China, it accounted for about 62% of electricity generation last year. President Xi Jinping has set a target for the nation to peak its consumption of the fuel in 2025, and aims to have non-fossil fuel energy sources exceed 80% of its total mix by 2060.

For India, coal is even more important, representing 72% of electricity generation. The fuel will still make up 21% of India’s electricity mix by 2050, BNEF analysts including Atin Jain said in a note last month.

Coal “can help the country meet its energy needs without depending on imports,” particularly as alternatives like nuclear have been hampered by high cost and safety concerns, said Debasish Mishra, a Mumbai-based partner at Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu.

Climate scientists insist the push by the top coal-consuming nations to allow prolonged use of the fuel is incompatible with efforts to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius from pre-industrial levels.

“Coal has to be abandoned for us to secure a safe climate future,” Matthew England, Scientia Professor at the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, said in a statement. “Net zero cannot be achieved without urgent action to leave the world’s reserves of fossil fuels in the ground.”

(By David Stringer and Rajesh Kumar Singh, with assistance from Kathy Chen)

Comments