Delta variant caused fresh supply-chain disruptions. Effects? Slower growth and higher inflation. Sounds like a perfect mix for gold!

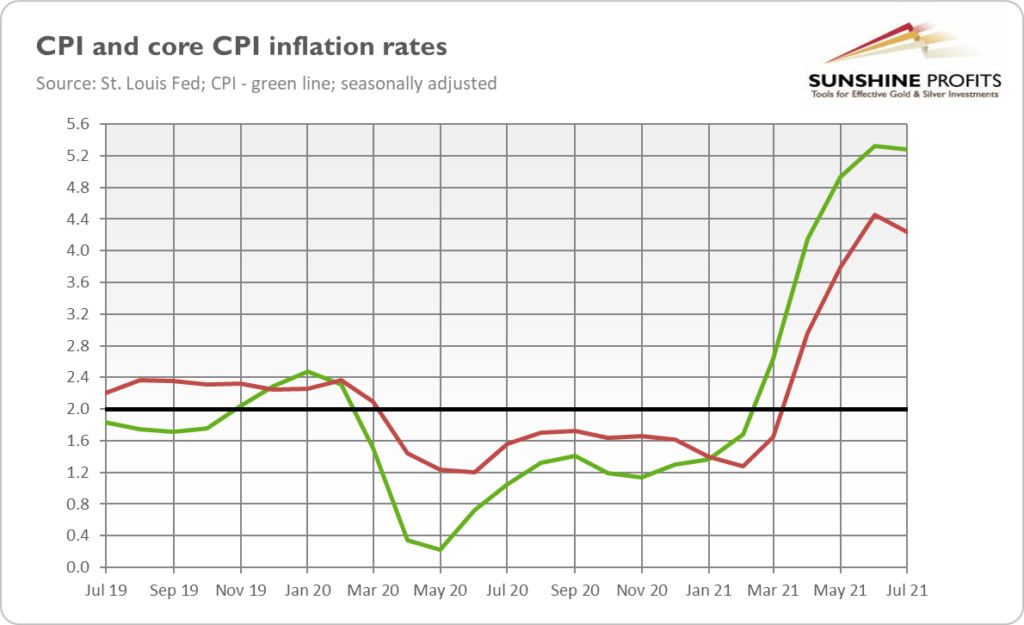

The Delta variant of the coronavirus is spreading all around the world. Although it won’t affect the world economy as much as the first wave of the pandemic, it will add to the already existing problems. Namely, the rising number of new cases will prolong the supply disruptions, hampering the GDP growth and strengthening the already high inflation (see the chart below).

In particular, last week, the Ningbo-Zhousan port in eastern China was partially closed until further notice after its worker was infected with the Delta strain. The problem is that it’s the world’s third-busiest cargo port, so its closure will cause fresh pressure to the already disrupted shipping industry.

The spread of the Delta variant and related disturbances in global trade have already caused Goldman Sachs to cut its forecasts for the US economy from 6.4% to 6% this year. “The impact of the delta variant on growth and inflation is proving to be somewhat larger than we expected”, the bank’s analysts explained in a note to the clients. The supply chain’s hurdles are expected to curb production and further raise prices, which would lower the purchasing power of consumers and limit their spending.

It implies that high inflation will likely stay with us for longer than the Fed thinks, just as I’ve been saying for a long time. The current situation shows a disturbing resemblance to the 1970s. As you know, inflation was surging then, but the US central bank was downplaying it, blaming the temporary effects of the first oil shock. The result of such a careless stance was the Great Stagflation and the need to aggressively hike federal funds rate by Paul Volcker. Inflation was defeated, but a double-dip recession emerged.

We also have a negative supply shock now (or, I should say, a series of shocks). It’s not an oil shock, but it’s also significant, as the issue broad-based — namely, the semiconductor shock and container shock, which hit all kinds of products. Semiconductors are key for the modern economy. They are used in various industries from consumer electronics to vehicles, and you practically cannot transport goods without containers. And as in the 1970s, the Fed believes that inflation is transitory and will go away on its own.

Yeah. Maybe it would happen if we had to deal with the supply shocks only. But the economy has also been hit by demand shocks – i.e., by the surge in the broad money supply and fiscal deficits used to finance cash transfers to the citizens and generous unemployment benefits. All this adds to inflationary pressures.

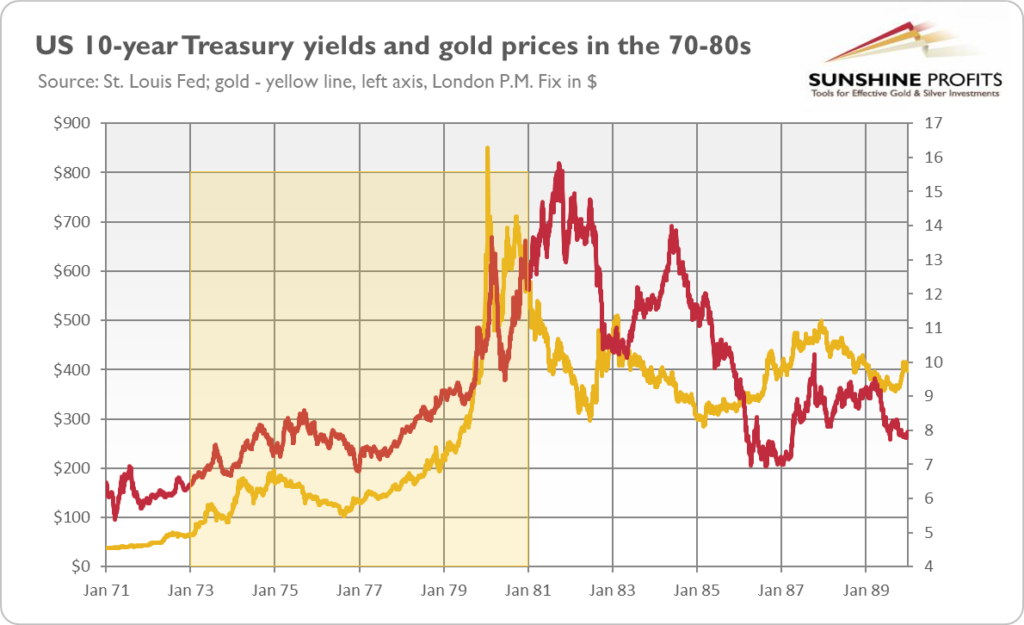

What does all this mean for the gold market? Well, slower economic growth and higher inflation due to the spread of the Delta variant are good news for gold. It brings us closer to a stagflationary environment, which should be welcomed by the yellow metal. Although gold doesn’t always protect against inflation, it served as a good inflation hedge during the 1970s, so we could reasonably expect similar performance during the potential 2020s stagflation.

Unfortunately, there is one big scratch in this picture: the Fed’s tapering of quantitative easing. More persistent inflation could mobilize inflation hawks to tighten monetary policy in a more rushed manner. As a result, the bond yields could increase, especially given that they are at very low levels, creating downward pressure on gold prices.

Luckily, history teaches us that bond yields can increase in tandem with gold prices. As the chart below shows, this is what happened in the 1970s. After all, what really counts for the gold market is real interest rates, and they could stay at an ultra-low level or even decline further if inflation surges.

Last but not least, the Delta variant is also likely to hamper economic growth. So, the Fed could actually become more dovish and postpone the end of its asset purchases, especially given that it has already expressed some concerns about the Delta spread. So, although the price of gold could decline further amid potential normalization in interest rates, inflation risk should provide some support or even materialize, pushing inflation itself higher.

(By Arkadiusz Sieron)

Comments