Cobalt price: 4 new Mutandas needed by 2030

The decision by Glencore (LSE: GLEN) this week to restart production at the mothballed Mutanda copper-cobalt mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo – the world’s largest cobalt mine – in 2022 will likely be one of many moves needed to ensure supply growth can match the trajectory of increasing demand.

The Swiss-based multinational commodities major’s decision to restart Mutanda follows a steady cobalt price recovery since the lows of August 2019 and rapidly intensifying demand from the electric vehicle (EV) and energy storage sectors.

Glencore announced the closure of Mutanda in August 2019, following an extended period of low prices. Meanwhile, the rollout of favourable EV policies by governments globally as part of the covid-19 pandemic recovery effort has seen fast-rising demand for the battery mineral under a backdrop of surging EV sales.

But cobalt prices only started a meaningful recovery in late 2020, according to London-based Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (BMI). Cobalt hydroxide cost, insurance, and freight in Asia is currently up by 125.1% versus August 2019, according to BMI’s April cobalt price assessment, which showed an average price of $44,025 per tonne ($19.97 per lb.) during the month.

When it last operated in 2019, Mutanda produced 103,200 tonnes of copper and 25,100 tonnes of cobalt hydroxide, compared with 199,000 tonnes and 27,300 tonnes, respectively, in 2018.

“This commitment from Glencore will likely be one of many that will be needed to ensure supply growth can match the trajectory of increasing demand”

BMI

Glencore cobalt trader Ash Lazenby told a BMI cobalt webinar this week Mutanda was expected to produce volumes approaching 20,000 tonnes of cobalt by 2025, highlighting a gradual but steady ramp as market demand increases.

The restart of the operation is fundamental to the cobalt market being able to supply the volumes needed by the battery industry to the mid-2020s, and even with the Mutanda operation back online, the market is expected to experience stock drawdowns and marginal deficits from 2023 onwards, says BMI.

“Whilst it is yet to be seen how the market will react to the announcement, in Benchmark’s opinion the outlined production plan is unlikely to see oversupply in the market, with much of the material likely destined to be locked up in long term contracts with key consumers looking to secure supply.”

The lithium-ion battery supply chain is undergoing a fundamental shift as previously theoretical forecasted EV consumption translates to real demand and as global automakers start to sell larger proportions of their fleets as electric vehicles,” says BMI.

“This commitment from Glencore will likely be one of many that will be needed to ensure supply growth can match the trajectory of increasing demand.”

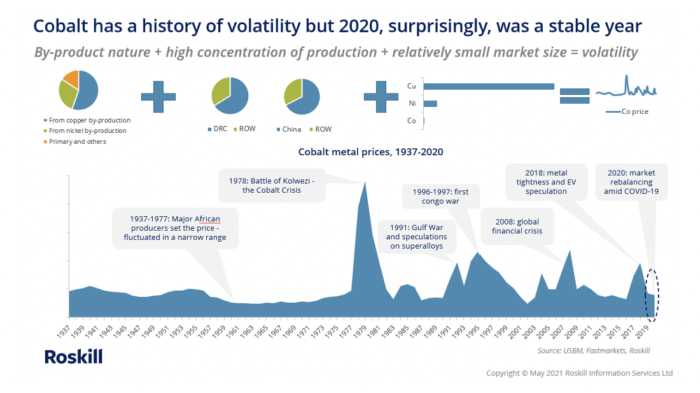

Price stability

Given the economic turmoil covid-19 has wrought on the global economy since early 2020, perhaps surprisingly, the cobalt price saw stability in 2020, Roskill senior analyst Ying Lu pointed out during a keynote speech at the 2021 Cobalt Conference this week. The metal has been noted for its stark levels of price volatility in the past.

Roskill believes there are two main reasons explaining the apparent stability. One is that after a period of oversupply, market fundamentals have improved over the course of 2020, largely as a result of the suspension at the Mutanda operation. Another factor is the cobalt market overall has been resilient to the covid-19 pandemic, which has limited downward pressure on prices.

Mutanda’s absence, coupled with logistic disruptions in Africa caused by the pandemic, resulted in tight hydroxide feedstock supply. This, in turn, led to a higher use of alternative feeds, such as cobalt briquette and scrap materials, over the course of 2020.

Lu said the biggest demand-side change over 2020 was the divergent trend between cobalt metal and chemical markets, with chemical demand surging and metal demand falling. This is mainly the result of more robust battery demand compared to other cobalt applications which rely heavily on metal feeds such as alloys and tool materials.

The lithium-ion battery supply chain is undergoing a fundamental shift as previously theoretical forecasted EV consumption translates to real demand

Roskill forecasts cobalt demand to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 7% in the period to 2030, underpinned by the uptake of electric vehicles globally and healthy medium-term demand from portable electronics amid the roll-out of 5G technology. The trend to reduce cobalt’s use in EV batteries will continue, but be offset by the growing market size.

To keep the market in balance, Roskill believes new supply equivalent to four ‘Mutandas’ will be required over the period to 2030. “While in the short to medium term, the timing of Mutanda’s restart would be a determining factor for market balances, longer term, we believe cobalt price needs to stay at a reasonable level to incentivise new investment,” Lu said during the presentation.

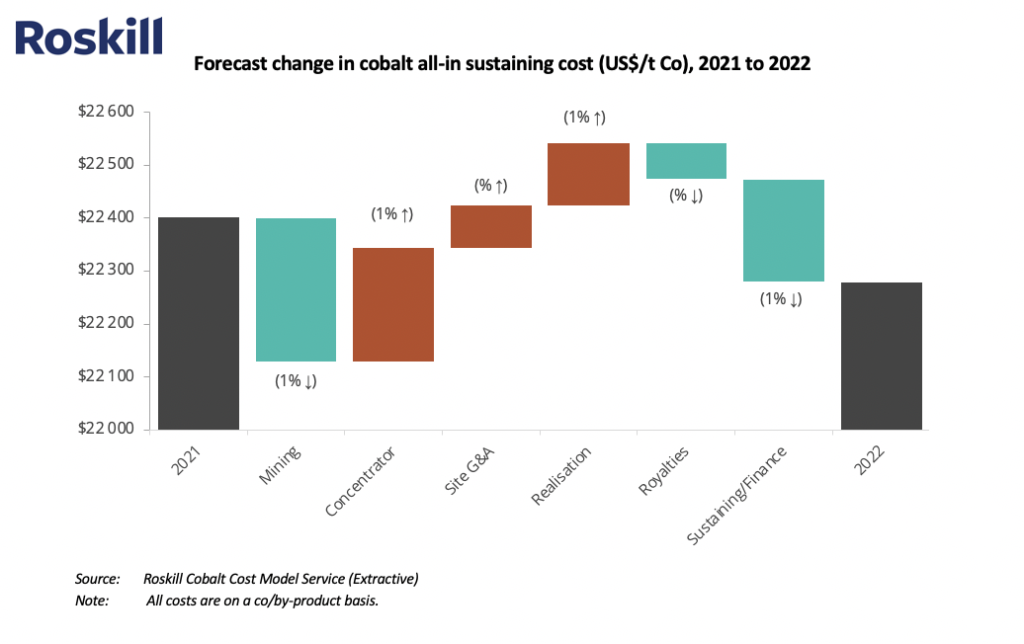

Lower cobalt AISC

The latest reading of Roskill’s cobalt cost model service (extractive) shows all-in sustaining cost (AISC) for producing the critical battery metal at stable levels through 2020 and 2021, at about $22,400 per tonne ($10.15/lb.), with the 2022 outlook calling for a drop.

Cobalt production is usually a by-product of copper and nickel, and positive price movements in these commodities mean producers are pocketing huge margins.

Given a 30% year to date rise in the copper price, the nickel price is chugging along nicely following the March correction, and the cobalt price averaging more than $44,000 per tonne ($19 per lb.) in the year up to mid-May, all active cobalt production capacity is cash positive on an AISC basis, says Roskill.

Mining costs are expected to fall through 2022 on lower stripping ratios and operating efficiencies implemented at major cobalt-producing mines such as Kamoto, Tenke Fungurume and Moa.

Roskill also flagged rising processing costs as offsetting much of the drop, mainly owing to falling overall mined grades.

In the medium to long term, Roskill expects that the cobalt cost curve will trend upwards and become left-skewed as higher metal prices incentivise higher-cost production to come online.

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments