Environmental disasters like the Vale tailings dam burst in Brazil and the Mount Polley tailings breach in British Columbia are the kind of things companies with a focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues are always striving to avoid.

In 2014 the BC mining industry got a black eye from Imperial Metals’ failure to prevent 24 million cubic meters of mine waste from hurtling down a mountainside and fouling Quesnel Lake, Hazelton Creek and other area waterways. The mine was shut in May 2019 not because of any costs related to the incident, but due to low copper prices. Seven years later, Imperial Metals has yet to face the consequences. A three-year deadline to lay environmental charges under BC laws passed in 2017, and a five-year deadline to lay summary charges under federal law passed in 2019, according to local news source the Prince George Citizen.

In Brazil, the 2019 dam collapse at Vale’s Córrego do Feijão mining complex killed 270 people and led to former CEO Fabio Schvartsman being charged with murder. Vale executives and members of the state government of Minas Gerais last year signed a $7 billion deal for repairing the socio-economic and environmental damage from the rupture.

Rio Tinto has also seen a barrage of negative publicity, following the destruction in 2020 of ancient aboriginal caves. The world’s second largest mining company behind BHP, in December was ordered to rebuild the thousands-year-old cave system it destroyed as part of an iron ore exploration project.

A parliamentary inquiry reported on by the BBC found that Rio Tinto “knew the value of what they were destroying but blew it up anyway”.

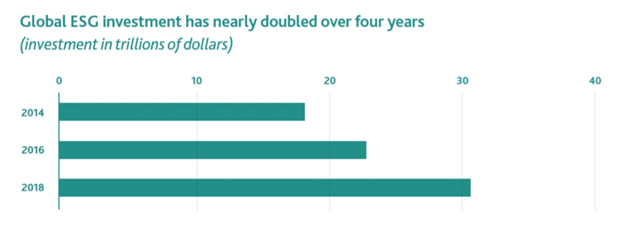

As shareholders and institutional investors demand that companies place more emphases on environmental, social and governance (ESG), the mining industry has had to overcome an often-checkered past regarding these issues.

For many year’s the industry as a whole managed to sidestep ESG, but the period of evading responsibility has come to an end and mining firms are increasingly being called upon to explain how they plan to incorporate ESG into their planning.

Whereas mining conferences used to be dominated by talks about production figures, commodity prices and other topics pertaining to hard assets in the ground, lately there has been a shift to discussing “softer” topics like climate change, involving indigenous communities in decision-making, and answering to feedback from shareholders.

ESG was a dominant theme running through this year’s AME Roundup conference in Vancouver.

Ross Beaty, chairman of Pan American Silver and Equinox Gold, said “It’s just critical. Every single meeting you have with investors, it’s number one on the topic (list).”

The renowned mining CEO and philanthropist injected some common sense into a subject matter rife with jargon, telling the Roundup audience, things like ESG and social licence are just “buzzwords” for being a good corporate citizen.

“All they mean is doing the right thing,” he said. “And that’s not rocket science.

“It means looking after your workers. It means making sure they go home every day healthy. It means looking after your communities. And it means looking after the countries you work in. Try to work with the national governments, paying responsible amounts of taxes and paying the royalties.”

Wheaton Precious Metals’ Randy Smallwood said European investors are getting particularly fussy about ESG, and he urged the mining industry to be less secretive and disclose more about their plans to mine more sustainably.

While there are obviously extra costs involved in implementing ESG policies, payback may come in the form of increased shareholders and shareholder confidence. Business in Vancouver’s Nelson Bennett explains:

Investors look to ESG performance and ratings as a proxy for good management and risk mitigation. It is essentially a playbook for decreasing risks a company might face in a country where it plans to build and operate a mine — from carbon emissions intensity and mine tailings management to indigenous relations and worker safety.

Bennett quotes Bonita To, a mining specialist for institutional investing at Scotiabank, saying in the past two years, there has been a big uptick in the number of institutional investors committing to responsible investment principles – about 3,000 of them, representing $303 trillion worth of investment under management.

Companies that need to raise capital will want to pay more than lip service to ESG, if they want the big bucks from institutional investors.

No kidding.

Other interesting speeches from Roundup 2021 concerning ESG, included Robert Friedland’s, who predicted the day may not be far off when copper or cobalt mined sustainably sells for a premium over metal extracted the old way. The billionaire investor and CEO said cobalt or copper could be priced differently depending on where its mined, its carbon content, and what company mined it.

During a recent webinar involving Brazil’s Vale, Anglo American and Chilean state miner Codelco, mining executives said that higher demand for copper is an opportunity for the industry to improve its image by adopting more socially conscious practices.

“The society will not tolerate the way we operated before,” Reuters quotes Ruben Fernandes, base metals CEO for Anglo American, referring to past mistakes such as two Vale dam bursts over four years in Brazil, and industry-wide issues such as pollution, deforestation and labor disputes.

It seems increasingly apparent that ESG is no longer a “nice to have”, but instead needs to be accounted for up-front by mining companies during investor presentations.

According to a recent study published by Ernst & Young (EY), losing social support, or social license to operate (SOL) is now seen as the main risk mining firms are facing.

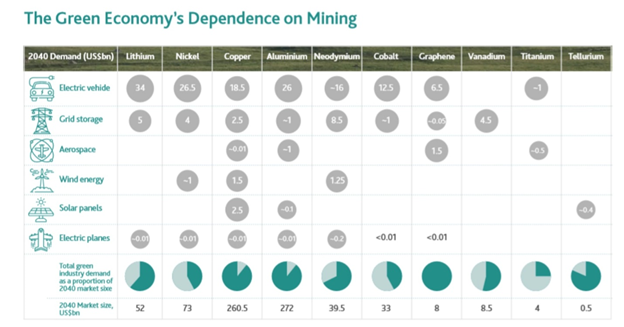

Another survey by BDO said stakeholders are demanding stronger engagement, transparency, and accountability, to the point where a social license will soon be akin to a mining permit. More positively, attaining a social license will shine a light on the industry’s importance in providing the raw materials for the future green economy.

“To meet the aspirations of consumers, mining is essential in the making of communications devices, consumer electronics and food production. Social license is the key to unlocking these positive mining outcomes,” says Sherif Andrawes, BDO’s global head of natural resources. “People see phones, cars, TVs but the link back to mining is often not made.”

Of course, with greater transparency, mining companies will increasingly be called upon to address climate change by reducing their carbon footprint.

Already, global miners are starting to pay attention to their internal practices. In the last quarter of 2020, a steady stream of environmental pledges pushed the industry’s ESG rating into positive territory from a negative reading during Q3 2020.

In a 20-company index, Newmont Mining was the leader, followed by global diamond miner De Beers. Rio Tinto improved its ESG score but was weighed down by the aboriginal cave’s issues. Vale came dead last.

According to London-based Alva, which assigns scores based on publicly available content, from social media to NGO research, community relations was the most negative topic, while greenhouse gas emissions (reductions) and energy management scored positively.

One of the most important KPIs for sustainable mining is procurement of local supplies. Stakeholders want to see concrete results that mining activity is benefiting the host country’s economy. (Canadian Mining Journal reminds of a recent high-profile case that reached the Canadian Supreme Court, wherein plaintiffs alleged that Nevsun Resources purchased from a supplier that used forced labor in building a mine in Eritrea — demonstrating companies who do not have supplier due diligence systems in place are at risk.)

In January Mining Shared Value (MSV), a non-profit initiative of Engineers Without Borders, announced that four mining firms, including Ivanhoe Mines and Lundin Gold, have adopted the Mining Local Procurement Reporting Mechanism (MLPRM), with two more expected to confirm shortly.

The MLPRM contains a set of disclosures for companies to provide information on, such as local procurement policies, how much is spent in host countries, and supplier programs. It is also designed to meet the requirements of other standards, such as the World Gold Council’s Responsible Gold Mining Principles and the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance standard.

More evidence of the growing importance of ESG in mining comes from a survey, conducted during the second half of 2020, of 67 decision-makers by global law firm White & Case.

Eighty percent of respondent think ESG will play a greater part in investors’ decision-making in the 2020s, and 14% expect ESG will lure generalist investors to allocate capital to the sector. Twenty two percent see ESG as a way to build greater resilience in future, second only to supply chain excellence.

One more point before leaving the topic of ESG and mining.

Back in September, as the gold price was trending higher, gold company CEOs were saying that ESG scrutiny intensified.

Generalist investors were keenly interested in profiting from skyrocketing bullion prices, but they didn’t want to do so at the expense of the environment and social issues.

“They don’t want to take a lot of risks, and a big part of the risk assessment is the ESG side of things,” Agnico Eagle’s CEO Sean Boyd told Bloomberg in a phone interview.

“Often it’s the first, and sometimes the only, discussion when we’re meeting with investors in Europe,” Newmont’s CEO Tom Palmer agreed.

Interestingly, ESG is now seen as the one issue, states Bloomberg, that can rile up investors and miners even more than cash. And unlike, say, mining cobalt or copper, which many associate with electrification/ decarbonization, gold-mining companies face more skepticism from investors because gold has less utility in advancing a green economy.

It isn’t only mining that has become enmeshed with ESG.

In 2020, ESG-focused ETFs recorded net inflows of $89 billion, almost three times the prior year, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

A great example is Norway’s sovereign wealth fund — at $1.3 trillion, the worlds largest. It has recently been reported that the Norwegian government that oversees the fund, expects climate and social issues to dominate investment decisions in the coming decades.

The fund, which returned 10.9% last year, has since 2004 followed strict guidelines including bans on certain weapons, tobacco and exposure to coal. A new set of guidelines would force fund managers to cut around 2,200 companies, roughly one quarter, from its massive portfolio.

Norway, which leads the world in EV adoption (in 2020 zero emissions vehicles were >50% of total car sales), is facing pressure to move further against the extractive sector. This week six environmental organizations including the World Wildlife Fund and Greenpeace called on Norway to stop plans to open ocean areas to deep-sea mining.

A March column in the Globe and Mail observes how the pandemic has exposed society’s vulnerabilities, including inequality, race relations and climate change.

It goes on to describe how NEI Investments, which has $9B in assets under management, highlights three ESG themes in its annual list of 50 companies it will focus on this year: human rights, inequality, and the energy transition, targeting net-zero emission commitments, adherence to global climate reporting and disclosure standards as well as plastics manufacturing, use and recycling.

Another manifestation of ESG is whats happening state-side.

A consortium of CEOs and other leaders of major US corporation reportedly met over Zoom this past weekend to discuss ways to push for greater voting access, amid new restrictions imposed by Georgia, Texas, and other states:

A new law in Georgia last month requires voters to provide a state-issued identification card when requesting an absentee ballot and limits drop boxes, among other restrictions.

This new “corporate activism” includes over 100 business leaders that joined the Zoom call, and an open letter by black executives condemning the voter restrictions.

It picks up on calls by dozens of business leader in January who condemned the storming of the US Capitol and vowed to withhold campaign contributions from Republican legislators who refused to affirm Joe Biden’s victory over Donald Trump.

Among the options being considered, are re-evaluating donations to candidates supporting restrictions on voter access; and reconsidering investments in states that act upon such proposals, Bloomberg reports.

Among the strong statements made, Delta Airlines CEO Ed Bastia said “The entire rationale for this bill is based on a lie: that there was widespread voter fraud in Georgia in the 2020 election,” and James Quincey, the CEO of Coke, who remarked, “The Coca-Cola Company does not support this legislation, as it makes it harder for people to vote, not easier.”

Once considered a topic of minimal relevance to the mining industry, which, unfazed by its poor reputation, seemed content to carry on, business as usual, ESG is finally getting the attention it deserves from an industry that has frankly had its head in the sand.

Like most things in corporate life though, it all comes down to money. Mining companies haven’t suddenly gained an environmental or social conscience; they recognize that to continue receiving funding from deep-pocketed investors/ funds, they will need to change their ways.

But creating wealth through mineral extraction and helping the environment (and the communities mining operates in) need not be dissonant concepts.

We at AOTH believe the two can co-exist, by mining responsibly. It doesn’t have to be complicated. Like Ross Beaty says,

“All [ESG and social license] mean is doing the right thing. And that’s not rocket science.”

(By Richard Mills)

2 Comments

Lloyd Penner

What a crap article. There’s omissions, out of context comments and full on lies in this story.

Richard Mills should be held to account for this.

Ric Roderick

Newmont may be a leader in protecting the environment. What concerns me, though, is the human rights of employees in mandating vaccinations as a requirement for employment. Haven’t enough people died suddenly from being forced to take something we know absolutely nothing of the ingredients? ESG should concern all things considering the bettering of the environment. I disagree with your policy and hope you give people the common decency to decide their own life and death health decisions.